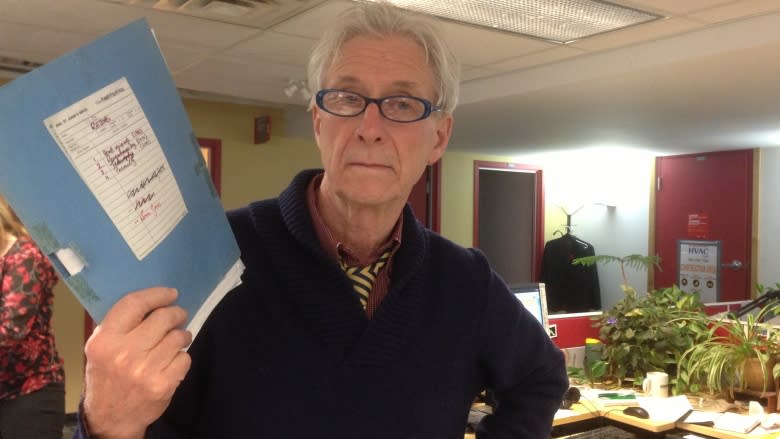

Rezori: A ghost from Mount Cashel that continues to haunt my desk

A few weeks ago I decided to clear years of clutter out of my desk and came upon a file labelled 'Shawn Janes,' the letters in red ink as if to emphasize that what I held in my hands again was seriously unfinished business.

The last time I'd looked at the file was 16 years ago.

I remembered it containing a number of letters, official documents and diary entries, all documenting the tragic life of a man who died at the age of 30 after unsuccessfully trying to come to terms with the abuse he experienced at the former Mount Cashel Orphanage.

I had every intention of telling the story back then, but the days of longer TV documentaries were coming to an end on Here and Now, and I felt a short version just wouldn't work.

So I parked the file in my desk where it slipped out of my mind.

Until now.

No resolution, no happy ending

There's no happy ending. There's not even anything resembling a resolution.

But that's what makes the story as relevant as ever.

Janes could have been an injured worker. He could have been a traumatized soldier. He could have been any of the countless people who fall through the cracks of our systems every day.

So here is his story — as it was then, as it is now, and as it will be while society works on designing better ways to respond to genuine suffering.

On the outskirts of Guelph, Ont., out of view from the rural road it's on, lies a small institutional compound called the Stonehenge Therapeutic Community. According to its official website, it offers long-term, intensive treatment (four to six months) for people "whose lives have been devastated by alcohol and drug abuse, and whose reality includes the fractured relationships, derailed careers and encounters with the legal system that so often result."

The names of the clients and patients who've come and gone there over the years are confidential. But we do know Shawn Janes was one of them.

We know it thanks to Conny Lenander of Toronto, a close friend.

Lenander was one of the guests invited to a small service back then in memory of Shawn Janes.

"There was a lot of people there," he recalled in a letter some time later. "Stonehenge alumni from all over Ontario, past and present staff, people that were at Stonehenge the same time Shawn was, plus the current crop of clients.

"Lucy Maclean (Stonehenge's executive director at the time) brought us all out to the grounds, and there was a hole dug in the ground with a small tree in it.

"When we were all gathered around, Lucy told us about Shawn, and his struggle, and how he would not give up on himself or his recovery."

A spot called Shawn's Place

She recalled how, half-way through his treatment, Janes received a phone call from his family in Corner Brook informing him his younger brother had committed suicide by hanging himself. Nobody at Stonehenge expected him to return after the funeral. But he did — he swore that he would while standing at his brother's coffin.

The service ended with Maclean explaining the spot would from then on be known as Shawn's Place, a designated quiet area where people could find inspiration to continue their treatment and not give up.

"Some people had little notes written about Shawn that we buried when we filled in the hole with the tree, everybody taking their turn with the shovel," Lenander recalled. "Many people cried openly."

Lenander had called me from Toronto a few months earlier wondering if I would be interested in telling Shawn's story.

Shawn, he said, had been physically and sexually abused while a resident at the Mount Cashel orphanage and was having a hard time getting the help he needed to deal with his demons.

Lenander and I exchanged several phone calls over the summer in which he kept me posted on Shawn's deteriorating condition.

Then came the call that changed everything. Shawn had died, worn out by enough suffering to overload a life much longer than his 30 years.

Lenander and I lost touch after that, and I have not been able to track down his current whereabouts.

But I do have two letters by him and a small stack of documents he sent me at one point.

'A wasted life'

So who was Shawn Janes?

Here's how he opens a 29-page, handwritten personal confession (he refers to it as his sorrows) while serving a two-year sentence in an Ontario maximum-security prison for robbery.

"I sit here now and I focus on a wasted life ..."

The year is 1995. He's 27 years old. He has seven more months of a two-year sentence to serve, and he has a lot to regret.

His childhood in a dysfunctional family in Corner Brook. The on-and-off exiles in foster homes. The three years he spent at Mount Cashel Orphanage (1981-1984), including the sexual, physical and emotional abuse he says he experienced there. His escape into the street and drug scene of Toronto. In short, his steady and unstoppable descent into living hell.

"I don't really have much to live for anymore," he writes. "I am a heroin addict and I can't seem to be able to kick the habit."

He wonders what made him the train wreck he's become.

Was it his father who abandoned the family early on? His mother with all her own hardships and breakdowns, who agreed to have him sent to Mount Cashel at the age of 13? The drugs he started using after leaving the orphanage to blunt his harrowing memories? All of the above?

'The best thing for me is death'

"I should really get some help for it," he writes, "but will that really work? I have tried it before and it does not work. The best thing for me is death. I just want to fall asleep and not wake up anymore, but I know it is not that easy."

No, it isn't. His confession proves it over and over. One moment he's in utter despair, next moment he sees hope again and grasps at the straws it offers.

"Why does God punish me like this. He knows how I feel about my life. Maybe he wants me to live longer. Maybe there is something out there for me."

He keeps orbiting himself like a satellite doomed by the gravity of depression to pass from the dark side to the light back to the dark side, over and over.

He's in a trap, and writing about it in his cell is all he has left.

"I guess this way I'm still able to live on a little longer."

He claims he only ever told one person what happened to him at the orphanage, "and they did not help me in any way, so now I sit here and trust no one."

He admits he's let the few people who still care for him down so many times, how could he expect them to listen even if he did open up. He's shut everybody out except his own warped self.

"I know I get some kind of pleasure from hurting myself. Then the bad feelings go away for at least a while. But these horrible shadows keep coming, searching my mind for a way to get in."

He tried to hang himself once. He tried overdosing several times. He cut himself even more often.

"Both my arms have been stitched up so many times that I'm ashamed to wear a short-sleeved shirt."

A determination to seek help

And yet, the later pages of his confession do show an increasing determination to seek help when he gets out of jail. His perspective over his suffering has widened. It's not just about him any more, it’s about others as well, and especially Lenander with whom he has been living for some years.

Janes started treatment at Stonehenge in early 1996, shortly after his release from prison. There he learned to talk about his experience. By the time he left 11 months later he'd also come to the decision to seek compensation.

He hired Toronto lawyer Howard Borenstein, who promptly sent a claim to the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador's civil law division.

The claim states that Janes was sent to the orphanage at the age of 13, "a time when he was young, vulnerable and in need of support and guidance. Instead, he was abused sexually, physically and emotionally."

The allegations include sexual abuse by one of the orphanage's volunteers and physical abuse by one of its Christian Brothers.

"Mr. Janes has previously been unwilling to come forward and has turned down requests to speak to the authorities in Newfoundland," Borenstein writes. "He is now prepared to come forward and is willing to speak to the authorities."

The reply came six weeks later.

"This is not a claim that the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador would entertain for settlement purposes at the present time," it says. It suggests Janes take his complaint to police "since they raise allegations of criminal conduct."

Janes' two-page statement, hand-written again, accuses a male volunteer at the orphanage of molesting him during a trip to a summer camp in Maine.

It describes at some length how, with the consent of the supervising Christian Brother, Janes ended up in the same bed with the volunteer.

"Later on that night in bed I felt (his) hand on my crotch. I pushed it away and said, don't. He stopped for a while and then continued to put his hand on my crotch again. This time I never said anything, only rolled over and pretended to sleep.

"The next morning I got up, I went down to the beach and sat down. I thought about what happened and decided not to say anything. If I had, they would not believe me anyway."

Many more incidents

According to Janes' prison diary, there were many more incidents, both before and after the camping trip.

Nothing came of the complaint to police, so Borenstein approached the liquidator of the Christian Brothers' estate in Canada. According to Lenander, the response was that Janes had waited too long to come forward.

A year had gone by since Janes decided to pursue compensation, and every door had slammed. There was nothing left but to go straight to the top — the premier of Newfoundland and Labrador at the time, Brian Tobin.

"Mr. Premier," he opens the first of at least three drafted letters, dated January 20, 1998. "My name is Shawn Janes. I am writing you this letter because I have nowhere else to go."

Written one day later, the second draft opens with even more desperation. "I write to you because you are my last resort."

The third draft is more subdued. No dramatic appeal, just the basic facts. "I'm writing to you with great hopes you can help me in my fight to get justice and closure with my dealings with the Christian Brothers, their volunteers, and your government."

He recounts his story. He says he's drug and alcohol free now. On orders of his doctor he can't work. He needs further therapy but can't afford it on a social assistance cheque of $930 a month.

'Mount Cashel hurt me'

"Mount Cashel hurt me, and that will never go away," he ends the letter. "But at least I can put some closure to it with your help. All I wish is a fair compensation from Mount Cashel. I want to thank you for reading my letter. I will contact you, or you can contact me. Thank you, Shawn Janes."

The contact came from Chris Decker, the justice minister of the day, instead. Since Janes had hired a lawyer, the matter was out of the government's hands. Decker referred Janes back to the police.

Four months later, Janes was dead.

"July 19th this year (1998) was a day I will never forget," Lenander recalls in one of his letters. "Shawn died in an easy chair two feet away from where I was asleep on a couch, between 10 a.m. and 11:30 a.m."

Janes' death had been ruled inconclusive. Lenander's own inquiries pointed to a heart attack after one of Janes' frequent anxiety attacks and violent heart palpitations.

Janes and Lenander had been living together for 10 years.

Lenander stood by Janes as he struggled with his addiction, took him back whenever he got out of jail, supported him when he decided to clean up his act at Stonehenge, walked with him when all hell broke loose after that.

"In Stonehenge, through group and one-on-one sessions, he started to talk about his past, and the more he talked the more he remembered, and when he left Stonehenge, in one way he was worse," Lenander explains. "Although he was drug and alcohol-free, the memories of his past that he had buried so deep were now right up-front."

Paralyzing nightmares

Janes fell into a pattern of paralyzing nightmares, awake and dreaming at the same time, eyes wide open, unable to move or speak.

"When I noticed it I poured water on his face and slapped him" Lenander recalls. "After about a minute he would come around and wake up. Sweat would drip off him. His heart would be racing, and he always looked very scared."

It got to the point where Janes dreaded going to sleep. He refused to sleep alone. The lights had to be on. Sleep, which used to be his refuge back in jail, now became a horror show.

"The kind of therapy Shawn needed we could not afford, so we did the next-best thing," Lenander says. "We used therapists we could afford, and at intervals we could afford."

They managed to get a $600 allocation from a fund set up in this province for Mount Cashel victims, "but as you know, $600 is a drop in the bucket."

Eventually they did find the right support group and therapist. Their hopes were high. They set up appointments. Janes died before he could make either.

Even early in his jail diary, when he still fills pages upon pages with endlessly circling self-pity, Janes admits that Lenander is the one person who has never betrayed him.

"Conny has always showed me love and happiness, and all I do in return is show shallow feelings."

Lenander saw it differently. "The hard, sometimes violent exterior hid a very compassionate, caring and loving person," he insists in one of his letters.

"I'm not trying to make a saint of him. I am only trying to tell you who and what he really was, and had he come from a stable, loving home he would have been a solid, upstanding person and would have made his mark in life."

Correction : A prior version inaccurately referred to Shawn Janes' surname in places as James. (Nov 23, 2014 11:22 AM)