Sounding the alarm on the growing dementia crisis

Catherine Kelly says the easy part of caring for her elderly mother is remembering to give her her medication. It's her mom's confusion and her loss of memory that she finds both heartbreaking and frightening.

"Having dementia is terrifying," says Catherine Kelly. Her mother, Isabelle, had a stroke eight years ago and developed vascular dementia.

"It's not easy to not remember what a toothbrush is, just imagine what that means to look at an object that you know is supposed to mean something to you and simply not know what it is," explained Kelly.

Dementia is a broad syndrome that impairs memory and other aspects of cognition like language, drawing and concentration. It's often severe enough to interfere with function. The number one cause of dementia is Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's International and The Canadian Alzheimer's Society have identified a coming dementia crisis as one of the major public health issues facing the world in the next 10 to 30 years.

Shirley Lucas, the executive director at Alzheimer Society of Newfoundland and Labrador, confirms it's a looming problem on the healthcare horizon here.

"There are currently over 8,600 people affected by the disease in the province. We are looking at double the numbers in 15 years," she said.

Catherine Kelly knows there will soon be a lot more families like hers caring for loved ones. She wants to sound an alarm about the state of dementia care in Newfoundland and Labrador, a province with the fastest aging population in Canada.

Kelly says her mother has received dementia care at memory clinics in both Ontario and Nova Scotia over the past eight years. She describes those facilities as a specialized one-stop shop for people with cognitive impairments. "There are geriatricians, geriatric psychologists and all kinds of community-based resources," said Kelly.

Kelly said comparatively, this province is decades behind.

"I feel very strongly that based on our experience in the last two years that families in Newfoundland and Labrador and people who have been diagnosed with dementia need a quality of care that we don't have here right now."

No geriatricians

According to Nova Scotia geriatrician, Dr. Ken Rockwood, there are 13-14 practicing geriatricians in that province. In Newfoundland and Labrador, there are none.

"To my knowledge, we don't have any full-on trained geriatricians in the province. We do have family doctors who have an extra year of training in geriatrics and complex care," said Dr. Aaron McKim, clinical chief of long-term care for Eastern Health — the province's largest health authority.

"Certainly we have tried to recruit geriatricians here, but it's hard to get the ball rolling. And if you're going to come here from another province and be the only geriatrician in the whole province that could very quickly become overwhelming," said McKim.

There are plans at MUN's medical school to implement its own geriatric training program to improve care for the elderly. There will be two six-month geriatric-training positions available to students in the fall.

According to Rockwood, that's a good start. He says having specialists in geriatrics is a critical piece in future healthcare.

"They can be persistent local advocates and catalysts for better care systems. They can translate the literature and provide good models of care for government," said Rockwood.

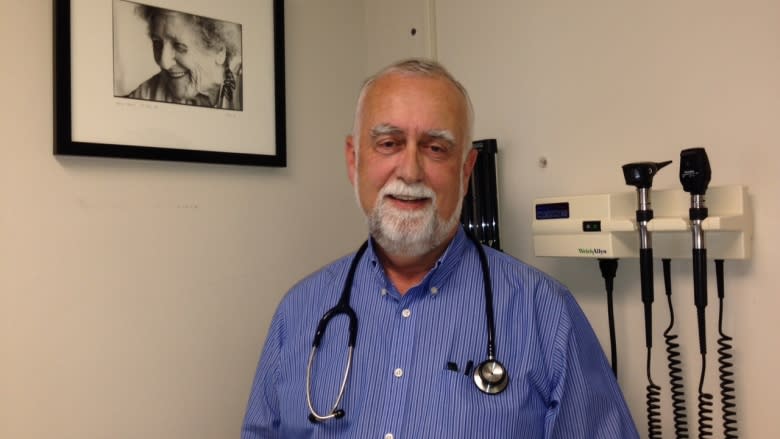

Dr. Roger Butler says he has been trying to be a advocate for the elderly for the past 20 years in Newfoundland and Labrador. Butler is a family doctor in St. John's with extra training in geriatrics.

"I'm past anger. I'm at disappointment now," said Butler.

Home-first approach

Butler insists there is too much emphasis on institutionalization. He's advocating a "home first" approach that would allow dementia patients to stay at home longer. Butler said patients do better in familiar environments.

"In Halifax, they have home first programs ... they've seen their acute care hospital numbers drop by 80 percent," said Butler.

The problem, according to Dr. Butler, is there isn't enough money being put into community supports for seniors. He said there should be less spending on institutions and more spending on allied health professionals. He says physiotherapists can help dementia patients with mobility issues in their homes and occupational therapists can reconfigure seniors homes to make them safer.

"In 1983 in Denmark, they said let's stop building nursing homes. They forced the community to respond ... with a much-enhanced home support system. They haven't bankrupted their nursing homes yet, and they're doing it for less dollars than we are doing it in Canada by about [a] 60-per cent cost," said Butler.

"I can keep them out of that emergency department or out of the nursing home, that's $50,000 the provincial government saves a year."

Butler said there are already many families in this province caring for dementia patients who are in crisis.

"We need a 30-year health-care plan and we need to hold our political masters to the fire on this one. The health care of our population is too important. This one disease will bankrupt us with the current way of thinking, we have to change," said Butler.

"I think the time has come to ask ourselves, is this really ageism? You know, our seniors in this province deserve better."

Eastern Health declined CBC's request for an interview on the issue of a "home first" healthcare strategy for dementia patients.

CBC was told there's nothing concrete and the authority would be getting ahead of itself by speaking on the issue.