On its 200th anniversary, a glimpse at the birth of the Roman Catholic Church in Manitoba

Two centuries years ago, after a more than 60-day journey, a pair of French-Canadian priests and a seminary student stepped out of a canoe onto the land of what would one day become Winnipeg.

One of them, a towering six-foot-four Roman Catholic priest in his early 30s, was Joseph-Norbert Provencher, soon to be known as the "giant of the West."

To the governor of the small settlement and the group of Métis residents who greeted them, Provencher and his companions were an "oddity," says Winnipeg historian Claude de Moissac.

"Nobody had seen black robes before," he said, using a term for Catholic priests based on their long black robes.

"They were the first priests to step foot on the banks of the Red River, the [Hudson's Bay Company] settlement."

That was July 16, 1818 — decades before the birth of Manitoba or Canadian Confederation.

Two hundred years later, Provencher's arrival is still seen as the birth of the Roman Catholic Church in Northern and Western Canada.

Provencher went on to lead what would become the archdiocese of St. Boniface, which is marking that anniversary this Sunday.

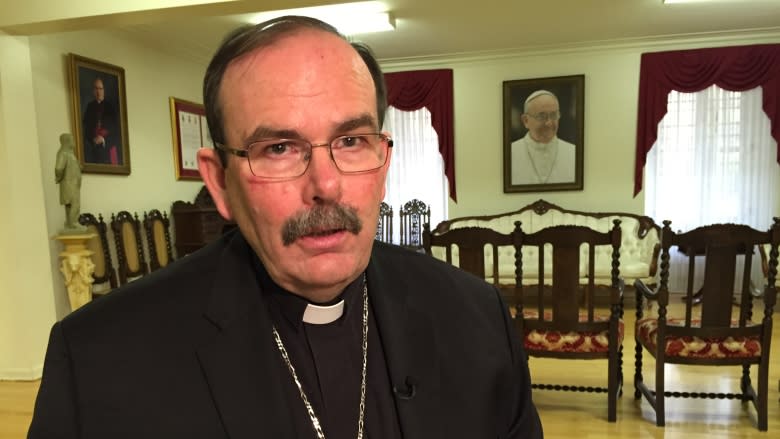

The archdiocese's celebration, called Jubilation, includes a public mass, musical performances, family programming and a re-enactment of Provencher's arrival, with Provencher portrayed by current Archbishop Albert LeGatt.

LeGatt, who admits he's a history buff, says Provencher himself is one of his favourite figures from the province's Roman Catholic history.

"He was a giant of a man, and that proved itself … morally and [in] determination," LeGatt said of Provencher.

"When he was first asked to come here, he said, 'I'm not worthy.'"

Provencher and his companions — fellow priest Sévère Dumoulin and seminarian Guillaume Edge — had been sent by Quebec Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis at the request of Lord Selkirk, who led the Red River settlement, and following a petition written by Métis residents in the area, de Moissac said.

They were sent with the mandate to spread Catholicism in the area, including converting Indigenous Peoples, conducting baptisms and overseeing legitimate marriages, as well as to help establish education, he added.

Provencher was named a bishop in 1822. In 1847, he became the first bishop of the diocese of St. Boniface.

He died in St. Boniface in 1853 at age 66.

He was succeeded by Alexandre-Antonin Taché, a young man whose arrival in the area in 1845 is a favourite story of de Moissac's.

"He wasn't a priest yet because he wasn't old enough to be a priest. He actually turned old enough to be a priest when he was on his trip here," de Moissac said.

"Bishop Provencher, upon greeting him, said, 'I asked for men and you're sending me boys.' Except the boy that they sent him became his successor and was probably as important, if not more important, in the history of Manitoba and of Canada."

De Moissac says the church they established would become instrumental in supporting some of Manitoba's earliest "social services," including hospitals and schools.

But over its 200 years, the legacy of the Catholic Church in Manitoba has included negative impacts on the province as well, including the church's role in establishing residential schools in the province.

"That's really a dark, dark period, and as a church, we really need to ask forgiveness for that," said LeGatt.

He calls residential schools a betrayal of the gospel.

"I feel the need to ask for forgiveness, to apologize, for all of the ways … from contact till now, that the Catholic Church, Catholic individuals, the Catholic Church as an institution has dismissed or even repressed the spirituality, the values, the teachings, the ceremonies, the wisdom of being on this land for 10,000 years — in essence, in harmony with this land, finding their soul in this land."

With that history in mind, LeGatt said the 200th anniversary must be celebration but also commemoration.

"Commemoration means you remember the past for what it was in its totality," he said. "And especially, the consequences upon various peoples of the life and the activity of the church."

The modern Catholic Church in Manitoba is multicultural, he said, including parishes that are Vietnamese, Korean, African, Hispanic and Polish, along with a vibrant Filipino population.

He'll be thinking about all the peoples of the church on the anniversary, he said.

"All the ways of being one, of continuing to try to be one, we recommit ourselves to that," he said.