It’s 2020 and Periods Are Still Holding Women Back

What defines January better than making a solid resolution? On New Year’s Day 2015, I did just that. While sharing photos of my annual ritual—a “polar bear plunge” into the icy Atlantic—a Facebook post caught my eye. Two teens in my community were seeking donations of tampons and pads for a local food pantry after learning about the hidden plight of our own New Jersey neighbors. Girls and women were missing days of school and work—and dealing with shame—because they were unable to afford period products.

My reaction was visceral. A public interest lawyer by day, I was consumed with questions about the ways public policy—or lack thereof—could impact the millions who menstruate. How many women in America were living paycheck to paycheck (or without a paycheck at all, or in prison), unable to manage the costs or burden of having a period? And why would something that’s a basic biological fact for half the population be excluded from policy making—in this case, food-pantry budgets?

I’ve been grappling with addressing these questions for the last five years—and what I’ve learned isn’t pretty.

The Cost of Having a Period in 2020

For the nearly one in five American teenagers who live in poverty, lack of menstrual products and support can lead to compromised health, lost classroom time, even disciplinary intervention. Those experiencing homelessness report isolation and infection caused by using tampons and pads for longer than recommended or by improvising with wadded toilet paper, paper bags, or newspapers. Incarcerated women and those held in detention—including the latest wave of girls separated from their families at the border—often must beg or bargain for basic hygiene needs, part of a degrading and dehumanizing power imbalance.

One of the many mind-boggling problems here is that tampons and pads are ineligible for purchases made with public benefits like food stamps. They’re not classified as “necessities” to qualify for an exemption from sales tax in the vast majority of states, and they’re not covered by health insurance or Medicaid, or included in Flexible Spending Account allowances.

Worldwide, the cost of having a period is also high. In Sierra Leone and Rwanda, around 20% of girls are reported to miss school because of their period. In Iran, nearly half of girls are so lacking in accurate education about menstruation that they believe it to be a disease. In parts of Nepal, menstruating girls are temporarily exiled, sent to makeshift huts with no protection from the elements—a practice that results in deaths every year.

Change. Period.

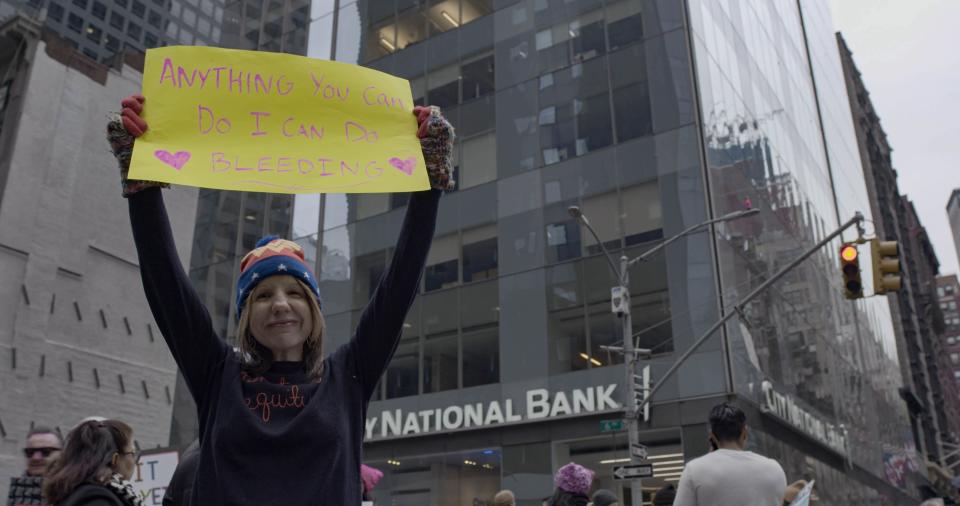

Thankfully, periods have gotten a lot of attention over the past five years. Women are throwing period parties, and influential women like Meghan Markle are speaking up, joining a global cohort of activists. We’re fighting for better education around women’s bodies; for more affordable access to tampons, pads, and menstrual cups; and against laws that make life more difficult for anyone with a period. And we’re making real change.

Since reading that Facebook post, one of the ways I’ve been putting my lawyerly skills to use is to end the “tampon tax.” For years, menstrual products have not been exempt from sales tax (while a dizzying array of items, ranging from fruit snacks to gun ammo to erectile dysfunction pills go tax-free). Kenya blazed the trail on this issue, scrapping the national tax on menstrual products in 2004, and more recently, activists have won victories in Australia, Canada, India, and Germany. A massive petition and campaign in England even forced the issue into negotiations over Brexit. In the U.S., 32 states have introduced legislation, and eight have succeeded in permanently ending the tampon tax. (As of January 1, California has joined the list, but only temporarily, until July 2023.)

The tampon tax is only one piece of the puzzle: In 2018, Congress passed bipartisan prison reform that mandates access to menstrual products in federal correctional facilities. (And, yes, Trump signed it into law.) Thirteen U.S. states have passed their own laws forbidding the withholding of menstrual products in county jails, state prisons, and juvenile detention centers.

And on the education front, governments are starting to mandate the provision of menstrual products in schools. Earlier this month a report out of Scotland showed just how powerful that is: 8 out of 10 students reported a positive impact, with almost two thirds saying they’re more able to stay in class during their period, and 25% describing improved mental health and well-being.

It feels fitting that all this progress over the past five years—and the work we still have to do—is also getting the Hollywood treatment. Last year, Period. End of Sentence., a documentary highlighting the stigma surrounding periods in rural India, won an Oscar. And today marks the premiere of Pandora’s Box: Lifting the Lid on Menstruation. The stories shared onscreen—told firsthand by Kenyan schoolgirls, health advocates in India, British lawmakers and campaigners, and formerly incarcerated women fighting for justice reform in the U.S.—make me feel inspired, angry, and motivated all at once.

The ability to manage menstruation is at the heart of what it means to participate fully and equitably in our society—and ensure a world that values dignity and equity for all. Five years in, I’m fired up to continue the fight in 2020.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf is vice president and fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, cofounder of Period Equity, and author of Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity.

Originally Appeared on Glamour