2nd story of babies switched at birth — same year, same Come By Chance hospital

A Newfoundland couple has come forward with a second story about babies switched at birth at the Come By Chance hospital in the early 1960s.

Their story has a happier ending than the case of Clarence Hynes and Craig Avery, but both cases raise questions about how hospitals identify babies to ensure they go home with their birth parents.

The nose didn't look right

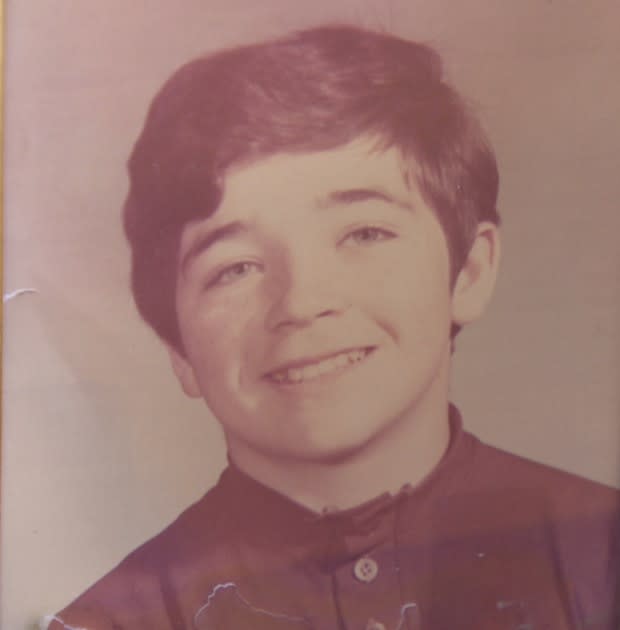

Fifty-eight years ago, Muriel Stringer was a 19-year-old coming home in a taxi with a newborn baby, her husband and her mother.

Three days earlier, on Aug. 8, 1962, Stringer had given birth to a baby boy, named Kent.

It was a long taxi ride, about 40 kilometres on dirt roads, from the Walwyn Cottage Hospital in Come By Chance to Hodge's Cove, on the east coast of Trinity Bay.

They took a break partway home at a restaurant in Goobies. Muriel Stringer and her mom stayed in the car while her husband, Cecil, went inside.

My baby had dark hair … and a nose like me. The nose didn't look right to me. - Muriel Stringer

"Me and Mom were there talking and looking at the baby and I said, 'Mom, he don't look like my baby,'" Stringer told CBC News.

"My baby had dark hair, a lot of dark hair, and a nose like me. The nose didn't look right to me. And my mother said, 'Oh, that's probably because of the bonnet and the clothes on him.' So anyway, we come on home."

The arm band

Stringer said her mother, Lilian Peddle, changed her mind when they undressed the baby.

"When she took the sweater off, she said, 'Oh my, it's not your baby.' There was a band on his arm and it was written, 'Baby Boy Adams.' He was only a day old, this baby. Mine was three days old," said Stringer.

They didn't have a phone so Cecil Stringer went to the Hodge's Cove Post Office.

"I phoned the hospital and the nurse answered. I told her what happened and first thing she said was, 'How come you didn't know your own baby?'" said Stringer. "But she checked and told me baby Stringer was there."

He called another taxi and left with Muriel's mother to bring the baby back to Come By Chance and pick up Kent.

"It was embarrassing," he said.

For Muriel Stringer it was the beginning of a long, anxious wait.

"Oh, I was frightened to death. I was thinking, 'What if he didn't have his band on his arm?' It scared me," she said.

Cecil Stringer doesn't remember exactly what happened when he got to the hospital, but Muriel Stringer says at the time he told her the other baby's mother was on the steps of the hospital waiting when he got there.

"This lady had only had her baby that day. So she was frightened to death. You know, anything could have happened to a newborn baby."

Wrong crib

At the hospital, a nurse said someone at the hospital had put the baby in the wrong crib, and when the Stringers were leaving, the nurse had just looked at the name on the crib.

"That was their explanation," said Cecil Stringer. "I don't know for sure if that's what happened."

Cecil and Muriel's mother collected Kent and headed home.

"Oh my, oh my, I was happy. Such a sweet boy. He still is," said Muriel.

The couple say they weren't angry about the switch — they say they were treated well at the Walwyn Hospital — but were grateful they got their baby back the same day.

The Stringers had five more children. One was born at home when a powerful winter storm closed the road out of Hodge's Cove. Four others were born, like Kent, in Come By Chance.

Not the only babies switched at Come By Chance

What's striking about the Stringers' story is that it's not unique.

The Stringer case happened in August, just months before Craig Avery and Clarence Hynes, born in the same hospital, were switched and sent home with the wrong families in December 1962.

And while the Stringers' switch was rectified quickly and happily, the story of Avery and Hynes is still playing out. They didn't learn about their mix-up until it was confirmed by DNA tests last year, and there has been no happy ending for them.

How many times did this sort of thing happen? - Craig Avery

They never met their birth parents, who died years ago. The two men, now in their mid-50s, say they're still struggling with the fallout of everything they thought they knew about their families being turned upside down.

Last year, Hynes and Avery launched lawsuits claiming negligence and suing Eastern Health for damages.

Avery says the Stringers' story leaves him with more questions.

"How many times did this sort of thing happen?" he asked.

Who's responsible?

In a statement of defence filed Feb. 11, Eastern Health says it's not responsible for what happened at the Come By Chance Cottage Hospital more than half a century ago.

"Neither Eastern Health nor any authority it replaced … ever assumed or was ever vested with the assets, liabilities rights or obligations of the Come By Chance cottage hospital," says the statement.

WATCH | Second set of infants switched at birth at N.L. hospital:

The health authority has asked for the action to be dismissed, with costs.

As for the Stringers, the health authority sent CBC News the following statement:

"Eastern Health has not been advised of another situation whereby a family went home from a cottage hospital with the wrong baby."

Modern patient identification

The Walwyn Cottage Hospital in Come By Chance closed in 1986. Babies are now born at facilities operated by the province's four regional health authorities. Eastern Health says it takes many steps to make sure babies go home with their birth families.

"Eastern Health has a number of stringent measures in place to ensure positive patient identification, including newborn babies," it told CBC in its statement.

Among those measures, according to the statement:

The infant is kept in the same room with the mother during the hospital stay and limits the number of times an infant is away from its mother.

When a mother and her infant must be separated — such as during a test or other procedure where the parent is not able to accompany the child — identification bands are checked when the infant is returned to the mother.

Upon discharge, all identification bracelets are again verified by a nurse, and the mother signs documentation to confirm the bracelet information is correct and the infant is her own.

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador