How 3D holograms and AI are preserving Holocaust survivors' stories

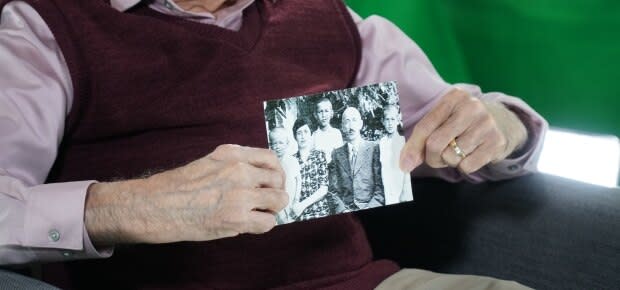

Max Eisen, 90, has lived his life by stubbornly looking ahead.

He survived losing his mother and siblings in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, and survived the camp himself, by focusing on getting through each day one hour at a time. He survived a 13-day death march by willing himself to keep moving his body forward a step at a time. He emigrated to Canada and started a business and a family by refusing to look back at what he'd lost.

Last month, though, he spent five full days in a studio in Los Angeles not only looking back, but going over every minute detail of his life for an high-tech project that will preserve his voice long after he's gone.

"I thought this was a very powerful tool, it was important," Eisen says.

The tool Eisen is referring to is the New Dimensions in Testimony Program.

It's part of Steven Spielberg's USC Shoah Foundation, which the director founded after making the film Schindler's List. For the past 25 years, the foundation has been recording the testimonies of survivors of the Holocaust and other genocides.

This new project, however, goes much further than simple recordings.

Interactive hologram

Using proprietary technology, the USC initiative employs machine learning and artificial intelligence to create holograms of survivors' stories that audiences will be able to interact with and question for years to come.

Eisen is the 25th person and the first Canadian to undergo the process, after another Canadian, Pinchas Gutter, piloted an earlier and less-polished version of it several years ago.

The process starts on a Monday morning and goes straight through until Friday afternoon. Eisen, like others before him, has to sit in a chair in the same position and wearing the same clothes while a USC Shoah Foundation staff member peppers him with hundreds of questions about his life and experiences during the holocaust.

The two are sitting in a specially constructed tent of green screens and surrounded by 26 mounted cameras that capture Eisen's responses from every angle.

After the week of filming, the USC team begins the arduous editing process. They transform Eisen's week-long interview into an interactive hologram.

The finished hologram will work with technology that allows users to ask it any question they want. The system will recognize words in the question and match it with an answer in its database in real time. Children and adults will essentially be talking to a person on a screen, who will look like they're listening to them and answering the questions in real time.

"When I first saw this, I sort of thought it was kind of eerie and this meant the end of life — you're only on a wall there hanging down now," Eisen says.

"But I've sort of come to realize this is a new technology and it could do a very big, important job."

Quest to preserve the past

For Eisen, participation in the New Dimensions Program is just the latest part of his personal quest to educate others about the horrors of the Holocaust.

For the past two decades, he has been giving speeches in schools and at community gatherings. He's returned to Poland many times with The March of the Living, a group that takes Jewish teenagers and adults on tours of concentration camps and ghettos in Poland.

He agreed to start talking about his past only after retiring from his business in 1991. It was his granddaughter who first started questioning him about it when she began learning about the Holocaust in school.

"I made up my mind then that I'm going to do this, I have to talk about it," he says. "I did promise my father that I would tell the world what happened there, so it was time."

Eisen's mother and siblings were killed upon their arrival at the Auschwitz concentration camp in May 1944. He lost his father a few months after they arrived.

For months, he and his father had suffered on a gruelling work detail, often labouring for 10 to 12 hours a day and surviving on very little food. After his father was selected for medical experiments, Eisen never saw him again.

Eisen credits his own survival to the mercy of the camp's surgeon, a Polish prisoner himself, after he was badly beaten by an SS officer. The surgeon kept Eisen in his clinic and put him to work as his assistant after he recovered from his injuries, sparing him any further labour.

"Of my entire family, over 70 people, I was one of three to survive," Eisen says,

Once he started opening up about his experiences in the Holocaust, Eisen has never stopped. His memoir, By Chance Alone, was published in 2016 and was the winner of 2019's CBC Canada Reads Competition.

The endeavour, spreading the truth about what happened to him and those around him during the Holocaust, has now become his full time job.

"This is actually my career now," says Eisen. "I was in business and I closed that book and I opened this book. And all these opportunities are just coming now and I don't refuse anybody."

His determination to educate as many people as possible about the Holocaust and the dangers of anti-Semitism is something he thinks is still relevant.

This was reinforced when an image of him in front of synagogue promoting Holocaust education in 2018 was defaced with the German word "achtung," which translates to "attention" — a word Eisen vividly remembers guards yelling at the prisoners in Auschwitz.

Eisen admits reliving his past hasn't gotten easier, but says the work is too important for him to stop — and the feedback he gets from students keeps him going.

"They keep telling me, you know, 'I've been a principal in this school for 25 years, I've seen these students, they have a span of attention of 15 minutes, and they were sitting here for an hour and a half and they didn't blink an eyelash.' That's rewarding," says Eisen.

Gruelling interview process

Kia Hayes, from the USC Foundation, has been tasked with interviewing Eisen for the New Dimensions project. She and her team spent months researching every aspect of his past, a process that culminated in more than 1,000 questions for him.

She says knowing Eisen could handle the gruelling interview process is why they selected him for the project.

"It's not just that the survivor can physically can sit for the five hours a day, five days a week, to tell their story. It's also, mentally and emotionally, are they able to? Do they want to? Do they feel comfortable sharing?," says Hayes.

"We want to know that we're not overburdening them with the amount of questions that we're asking, and that's really important to us."

The types of questions Hayes asks Eisen are interesting, too.

Beyond questions about his childhood and wartime experience, her team has to think of what a child without much knowledge of history might ask of a Holocaust survivor in the future. So, questions like 'Have you met Hitler?' and 'Do you hate Germans?' are included, because of the fact that children are likely to ask them.

"They [children] are curious. They want to know things like that. So we need to make sure the questions we're building out include that level of curiosity," explains Hayes.

And Eisen is more than willing to answer all of those questions. He says it's essential that the stories of Holocaust survivors do not die with them, and the interactive holograms help keep the stories alive for future generations.

"It's amazing, who would've thought something like this would be possible?"

Eisen's interactive hologram is now in the editing stage and will be ready to be installed in museums and travel to schools in about a year's time. He says the experience was a once in a lifetime opportunity to preserve his legacy.

"That's why I keep doing this, and moving, and going, and talking. And this is what other survivors are doing — when we are no longer going to be here, there's got to be some other tools that these students and next generations will need to hear and see."