Up to 40% of UK retail space is not needed – here's what can be done with it

COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on many retailers. Since tough new restrictions were introduced in parts of the UK during October, footfall on high streets, shopping centres and out-of-town retail parks has fallen: it is now down 32% year on year, with regional cities bearing the brunt. Though retail as a whole has now recovered to pre-COVID levels, many physical retailers are not paying rent, and some landlords are considering legal action.

But as dreadful as COVID-19 has been, retail had serious existing problems. The reality is that there is far too much retail floorspace in the UK. Dealing with it is going to be one of the big challenges of this decade.

The retail crunch

Retail employs more people than any other UK sector – about 2.9 million, two-thirds of whom work for the 75 largest companies, turning over around £394 billion in 2019. In recent years, these businesses have been wrestling with higher staff costs due to increases in the minimum wage; higher business rates (property taxes), especially for large shops in prime locations; a weaker pound since the Brexit vote of 2016, making imports more expensive; and online competition.

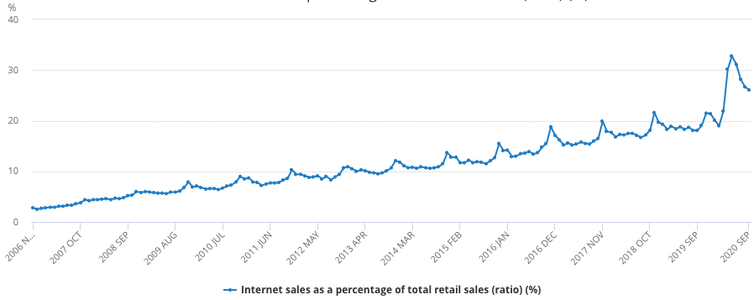

The UK already had the third highest level of online shopping in the world before COVID-19 (16% of total retail spend, exceeded only by China and South Korea). Now online has become even more powerful, peaking in June at one-third of all UK retail sales. Wherever it settles, it will be higher than before the pandemic.

UK online sales as a % of total retail

Thanks to online shopping and the other pressures on physical retail, as much as 40% of shop floorspace may be permanently surplus to requirements. This is about 42 million square metres, equivalent to 175 Westfield Londons, 227 Metrocentres or 284 Bluewater shopping centres.

This helps to explain why Intu, owner of large shopping centres like Gateshead’s Metrocentre, Manchester’s Arndale and Trafford Centres, and Birmingham’s Merry Hill, went into administration in June. Many of its centres are now being sold or transferred to new management as the Intu Group is dismantled.

Other big landlords have struggled too. Hammerson (whose centres include Brent Cross, Birmingham Bullring and Bristol Cabot Circus), British Land (Sheffield Meadowhall and Drake Circus in Plymouth) and Land Securities (Bluewater in Kent, Leeds White Rose and Buchanan Street in Glasgow) have been on a stock market rollercoaster and face a similar dilemma with their oversupply of retail floorspace.

Share prices of major UK retail landlords

Mitigating factors

One silver lining of the pandemic has been landlords having to reframe their relationship with tenants. As proposed by the UK government’s voluntary code of practice, which came out in June, landlords must work with retailers for everyone to survive this period. This includes cutting rents to more sustainable levels.

For example, the market is seeing a return to turnover rents, where tenants pay a percentage of turnover rather than a nominal “market” rent unrelated to prevailing economic conditions. Such flexibility may reduce empty floorspace to a certain extent.

Another mitigating factor is that most retailers will still want some kind of presence on high streets or shopping centres. Indeed, the lockdown saw a big shift in domestic spending to local convenience and neighbourhood stores in the suburbs.

Retailers have also been blending traditional and online sales by encouraging customers to order for next-day home delivery or click and collect. This gives them another reason to retain a physical presence. At the same time, online retailers such as Amazon are opening high street stores to complement their offering.

The way ahead

Despite these innovations, there is still likely to be a large surplus of physical stores overall. So what can be done?

Some space might be used as offices, though the pandemic has seen a huge rise in remote workers, some of whom may never resume the office commute. Making stores into cinemas, restaurants or bowling alleys is hardly a solution either, when the leisure sector is among the hardest hit by pandemic restrictions.

Perhaps the most productive opportunity is to redevelop for a more varied mix of complementary uses – as echoed by leading retailer Bill Grimsey’s call to “build back better”.

In towns and city centres, this could include universities and colleges expanding their campuses; galleries, workshops and showrooms for the arts and creative sector; community enterprises and hubs; and health and wellbeing services which will be essential in the post COVID era, such as social care and mental health. Such uses could be assisted by public funding and landlords recognising that some tenants paying low rents are better than no tenants at all.

Some redundant buildings and vacant upper floors could also be turned into homes – echoing the return to urban living of the 1990s and noughties. The government could reintroduce the living over the shop (LOTS) scheme, which subsidised such conversions during that era.

Yet many buildings do not easily lend themselves to residential use. Utilities may struggle to provide refuse collection, water and sewerage connections, and parking spaces. Planning relaxations may sometimes remove the need for planning permission to change to residential use, but there are still complex building regulations, especially regarding fire protection and emergency access.

Traditional high streets also have multiple owners, who don’t always cooperate. Town centre managers and business improvement districts (BIDs) can help here, though we may need to see BIDs that levy additional business rates on landlords rather than tenants, like in Germany, to bring landlords to the negotiating table.

Shopping centres at least have the advantage of a single owner. As destinations in their own right, they are often regarded (rightly or wrongly) as too big to fail, particularly those woven into the fabric of city centres, such as Liverpool One or Eldon Square in Newcastle. Keeping them functioning will therefore be a high priority for the authorities.

Some out-of-town shopping centres had plans for new residential and leisure developments even before the pandemic. An example is the project to build 2,000 new homes around the Gateshead Metrocentre. The idea would be to reorientate the centre, diversifying the mix of uses to serve a wider community, though it won’t be easy to create new family homes in an environment designed around the car.

Such challenges are not particularly new: 25 years ago we would have called it “mixed-use regeneration”. This time it is driven by excess retail space, ironically much of it built on the former industrial sites that were regenerated in the 1980s and 1990s.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Paul Michael Greenhalgh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.