40 years later, this mom looks back on that time her baby's ultrasound made the news

Back in 1979, having an ultrasound image of your unborn child wasn't exactly a matter of course.

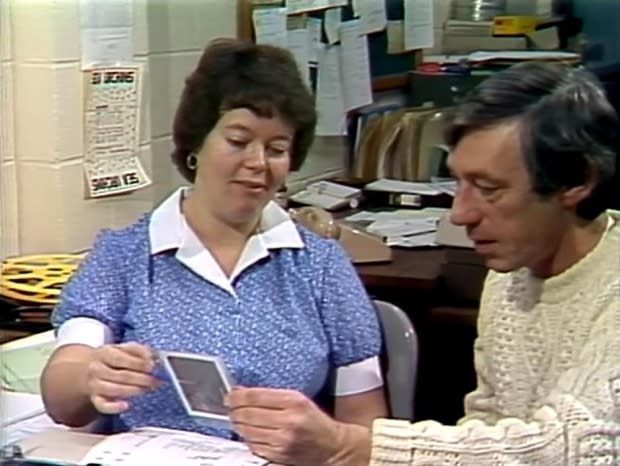

But Judy Arnott, then a 29-year-old working at CBC with Here and Now, thought she might be expecting twins, and scored a lucky session with a radiologist to figure it out.

"I had been hoping, for some time, to have a baby," she recalled, and being able to see it growing inside her evoked emotions she had difficulty putting to words.

"It's just amazing, I can't even really express it. Only somebody pregnant for the first time ... would have experienced that feeling."

This week, CBC News dug up old footage of Arnott's chat with a reporter about the ultrasound image, then still quite a novelty in Newfoundland.

After CBC shared it online last week, Arnott's family found it, and couldn't believe Arnott's excitement at something now so run-of-the-mill.

"I think ultrasounds were performed, but maybe not as frequently as today. There had to be a reason," Arnott said, remembering that friends — and nosy coworkers — would all gawk at the photo when she pulled it out to show them. "I didn't know anybody else who had an ultrasound picture."

And those who did have ultrasounds didn't always get a copy of the test, she said.

A technician made an exception for Arnott that day.

"I'm not sure if they were passing out pictures to anyone who asked," she said, "but it was a stormy day, and they weren't busy, and the technician and I had lots of time."

Arnott even carried it with her to a Christmas party that year. "Of course, everybody was hauling out pictures of their babies, and I said, 'Well, I have something to show you.'"

Limited technology

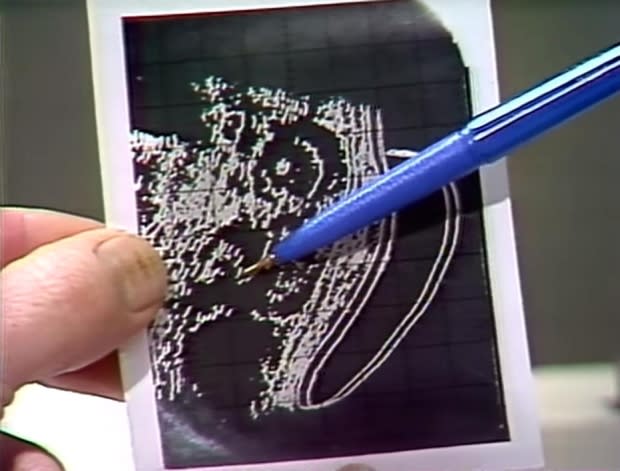

The ultrasound scan, which uses high-frequency waves to create an image of the fetus in the womb, couldn't do much in the 1970s besides predict how many kids a mother could expect. Even determining the sex of the fetus presented a challenge.

"Back then, it had to be pretty obviously a baby boy," Arnott said, before a technician could make the call.

Radiologist Maureen Hogan, a clinician and assistant profession at Memorial University, said the technology has come a long way since the grainy early days of ultrasound imaging.

"What they used it for back then would have been very primitive, very basic," Hogan said, explaining that the resolution of the photographs would have been too low to detect much.

Now, Hogan said, ultrasounds can be used to flag genetic issues with a fetus. The addition of doppler technology, she said, meant technicians could look at bloodflow and heart development as early as six weeks into a pregnancy.

"You could listen to the [fetus's] heartbeat, and then realize, with research, that a certain heartrate is normal," she explained. "You can look at the brain, the stomach."

Abnormalities of fetal anatomy — such as a thicker neck than usual — could indicate a condition such as Down syndrome, Hogan said. "You can measure the [fetus's] neck down to millimetres."

Back in the 1970s, they weren't doing that, she said.

"It's come so far now that it's a staple of what we do. Everybody gets an ultrasound."

All grown up

Arnott, who ended up having four children, said she forgot about making the news until her kids saw the footage for the first time. "They were laughing their heads off," Arnott chuckled.

"It's funny watching your mom from 40 years ago," agreed Sarah Arnott, the now-grown baby in the photo.

Sarah now has two children of her own. Without sonograms, she said, the pregnancies would have been nerve-wracking.

"Ten fingers, ten toes, they were all counted," she said. "To think that they didn't have those assurances that we do now — it was definitely different."

Read more articles from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador