5 years into agreement, what does treaty education look like in Nova Scotia?

Each day, Jenny MacLean's primary students take time to read from a classroom treaty they created together.

It's a reminder of the promise they've made to be good friends, and one way the teacher at Brookland Elementary School in Sydney, N.S., is carrying out the province's commitment to bring treaty education to students in Nova Scotia.

"We're learning things that I didn't learn in school and it's important now that children go through the school system and have an accurate account of what happened in Canada," said MacLean.

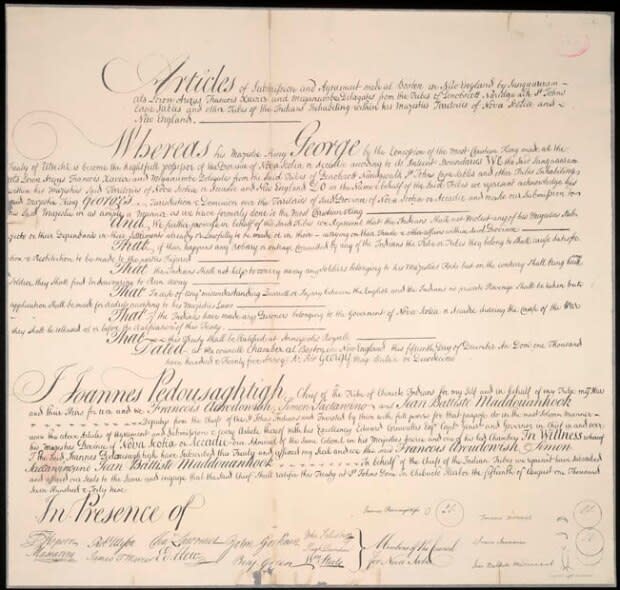

Five years ago today the Nova Scotia government signed an agreement with Mi'kmaw chiefs to implement Treaty Education in the province's public school system.

The province says that promise is being fulfilled, with treaty curriculum now being taught to Primary-Grade 12 students, although resources and programs continue to roll out.

Embedding Mi'kmaq perspectives in every corner of the curriculum is slow and steady work, says the province's treaty lead.

"Teachers want to teach about treaty education, they're just afraid to get it wrong so we're trying to develop as much support as we can in creating that comfort in being able to teach that," said Jacqueline Prosper.

A new urgency for treaty education

The lessons, from how to perform the Mi'kmaq Honour Song to reading story books about Mi'kmaq culture and traditions, were developed by the Indigenous education authority Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey.

Prosper said the authority works with a group of Mi'kmaw writers, researchers and artists to develop curriculum that shares treaty education in a fun and informative way.

"We were the First people of this territory and we've been left out of the story all this time," said Prosper. "Mi'kmaq are going to see themselves in the curriculum and be able to have pride in who they are."

This school year, with an historic dispute over Mi'kmaq treaty rights playing out in southwest Nova Scotia, Prosper says teaching students about what the peace and friendship treaties say and why they matter has taken on new urgency.

The Sipekne'katik First Nation's Mi'kmaw-regulated, rights-based lobster fishery is now operating in St. Marys Bay but has been met with fierce opposition from some commercial fishermen.

"Being able to have an understanding of what's actually happening, why and where it came from, you know, it's important to have that background information," Prosper said.

It's a message Chris Boulter, executive director of the Tri-County Regional Centre for Education, has been trying to share with schools in his area, where many students come from fishing families.

He sent a letter to families last Friday urging teachers and parents to use the fisheries dispute as a teachable moment. Boulter also said that discrimination and harassment by members of the school community is not acceptable.

"These are adult conversations in the community. We know that students are watching ... as things play out. Our goal as a system is to ensure that schools are safe and welcoming for all students," he said. "We're not shying away from these conversations."

COVID-19 delays some training

The new curriculum for Primary to Grade 2 students features seven picture books accompanied by animal puppets that celebrate Mi'kmaw culture and traditions.

The books were first rolled out at Cape Breton elementary schools last year with the expectation classrooms across the province would receive them this fall.

COVID-19 changed that.

With schools closed in the spring, teachers' professional development days were put on hold and classrooms that do have the resources aren't able to use the puppets right now due to social distancing restrictions.

No one from the Department of Education's Mi'kmaq Services branch was available for an interview, but a spokesperson said that the focus this fall has been on school safety and staff are working to reschedule training for teachers.

"While training is rescheduled, we continue to offer Treaty Education in our curriculum; and we're hearing about learning opportunities that teachers and principals have been arranging like virtual language sessions with Elders," Violet MacLeod said in an email.

MacLean, who is not Mi'kmaw, has been teaching Treaty Education to her students for several years and said she continues to be nervous about doing the material justice, especially when it comes to sharing Mi'kmaw terms.

"It's just important that we are exposing students to the culture and it's OK to say to the students, I'm not quite sure but I can look it up or I'll play it on the computer for you so you can hear the language," she said. "I think it's OK to make some mistakes as we go, but to keep learning."

Prosper, who used to teach Grade 7 social studies, said she's excited to see how far the province has come in the last five years.

She remembers a time when the curriculum in Nova Scotia was based on Indigenous teachings from elsewhere in Canada.

Now, students learn the nuances of the province's 14 Mi'kmaw communities, including Kjipuktuk, she said.

"It's important to understand that, you know, one Mi'kmaw isn't all Mi'kmaq. There are many voices. There are many understandings, many interpretations," Prosper said.

"I love to see the beauty of who we are as a Mi'kmaq nation being put out, rather than just our traumatic and horrible experiences in our relationship with Canada. We get to really show who we are and how beautiful it is to be Mi'kmaq."

MORE TOP STORIES