7-year-olds with breakouts: Why the face of acne is getting younger

More doctors are seeing younger patients with breakouts — but why? (Infographic: Schweiger Dermatology Group)

Waking up with a big zit before the school dance or a first date is usually thought of as angst-ridden rite of passage for every teenager, but experts say that hormonal blemishes are now showing up in even younger children.

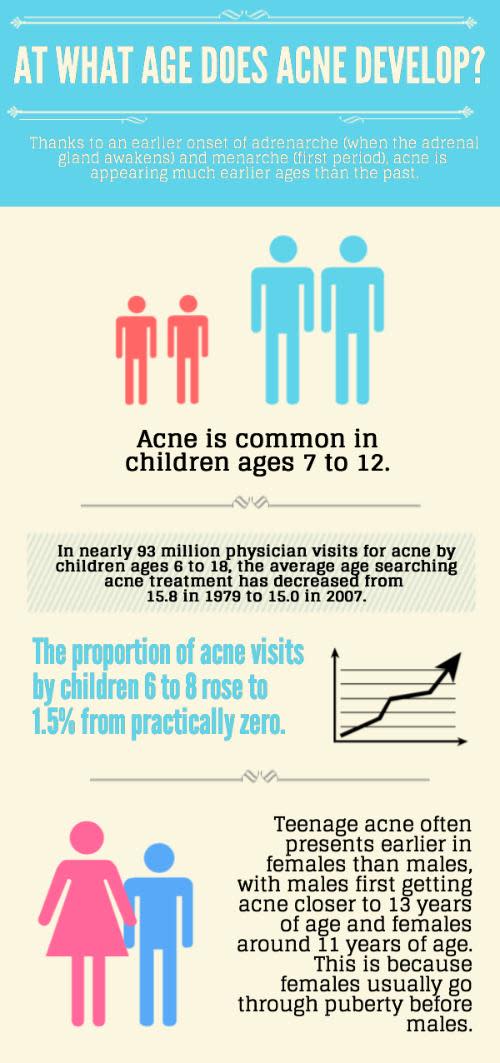

“Thanks to earlier onset adrenal gland awakening and menstruation, acne is now appearing in kids as young as 7,” says a New York dermatologist, Eric Schweiger, MD, of Schweiger Dermatology Group. In previous generations, teens who broke out earlier than their peers would typically start seeing spots around the age of 12, he adds.

In a study published in the journal of Pediatric Dermatology, researchers collected data from 1979 to 2007 to evaluate whether acne is now showing up at younger ages. “Analysis revealed a significant decrease in the mean age of children seeking treatment for acne over this 28-year period,” say the study authors — who added that the evidence supported an increasingly earlier onset of puberty in girls.

Related: 7 Things You Thought Wrong About Early Onset Puberty

The same study found that the proportion of children aged 6 to 8 who visited the doctor for acne treatment has risen from nearly zero to close to 2 percent since 1979.

With more doctors receiving younger patients, the American Acne and Rosacea Society in 2013 presented the first detailed, evidence-based clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric acne to help experts navigate the landscape. “Acne severity dictates protocol, but with younger patients, we tend to avoid certain oral antibiotics and instead focus on topical treatments,” says Schweiger.

A growing body of evidence has emerged on the related phenomenon of early puberty (sometimes referred to as “precocious puberty”). In the recently-published book, “The New Puberty: How to Navigate Early Development in Today’s Girls,” Louise Greenspan, a pediatric endocrinologist at Kaiser Permanente, and Julianna Deardorff, an associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, find that it’s the national obesity epidemic and family stress that are the biggest driving forces behind girls getting earlier periods.

Related: The One Thing Most Of Us Are Stressed About

“Body fat secretes estrogen, a hormone that is normally released from the ovaries during puberty and is responsible for breast development. The more body fat one has, the higher the likelihood of excess estrogen secretion, and consequent premature puberty,” Greenspan tells Yahoo Health. Other symptoms, like acne breakouts and the growth of body hair may follow.

And surprisingly, studies have found that emotional stress in a young girl’s life has figured strongly into body changes. Living in an unstable home with high levels of conflict heavily correlates with the onset of early puberty. And in a home without a biological father present, a girl is twice as likely to get her period before the age of 12 as compared with a girl whose father is at home, say Greenspan and Deardorff.

While hormone-mimicking chemicals in plastics and personal care products, as well as hormones in meat, dairy, and soy may be a concern and have certainly received much press, research has still not found definitive evidence that they are directly correlated with early puberty, say Greenspan and Deardorff. One dietary exception is soda. Regardless of their weight, girls who ingested sugary drinks daily were more likely to go through puberty early, according to new research from Harvard School of Public Health.

So why all the concern over some zits popping up ahead of schedule? First, girls may be experiencing the accompanying body changes before they are emotionally old enough to handle them, but in addition, studies have also linked early puberty with health risks later, such as depression, breast cancer, and substance addiction.

Experts say that most research done so far has been preliminary, and that we’re only beginning to learn how the process of puberty may be currently evolving in response to the changing human environment.