Advocate applauds plan to train health-care staff to deal with patients in distress rather than police

A Winnipeg mother who lost her son to suicide after he was discharged from hospital following a suicide attempt supports a plan to see trained hospital staff take over responsibility for watching patients who may be experiencing psychological distress while they wait in emergency rooms.

Currently peace officers are required to wait with patients they've brought to hospital who are experiencing mental distress or who may have a potential for violence, until they're admitted.

A Manitoba Health document obtained by CBC News details plans for early implementation of health-care legal changes that would involve training in violence prevention and management, de-escalation, and emergency mental health and addiction for security guards, health-care aides, mental health liaisons and emergency department nurses at three Manitoba hospitals.

Bonnie Bricker says it's a step in the right direction.

"We're not actually utilizing that police resource in the proper way," she told CBC News Saturday.

"Right now they pick somebody up who is suicidal and they take them down to the emergency department and they have to sit with them until that person goes in — that could be seven hours.

"In the meantime somebody is getting robbed and stabbed in the street, that does not make sense."

'A completely different outcome'

Bricker's son Reid died by suicide when he was 33 in October 2015, shortly after being released from the hospital he went to for help. She has since become an advocate, calling for mental health overhaul in the province.

Currently, under the Mental Health Act, peace officers have the right to take a person who needs psychiatric help into custody against their will, with oversight from doctors or health-care management.

The Mental Health Care Amendment Act, or Bill 3, passed in 2016. It has yet to be proclaimed but if it is, it would give peace officers the ability to transfer custody of a patient detained under the act to "qualified persons at health care facilities."

The early implementation is set to take place at the Health Sciences Centre in Winnipeg, Brandon Regional Health Centre and Selkirk Regional Health Centre.

Bricker says training frontline staff at hospitals is a good start toward the changes she's been advocating for since her son's death.

"I'm telling you, that person who is suffering from anxiety and depression, they're not happy to have the police with them, that makes it worse," she said.

"Instead of you sitting with everybody staring at you in the waiting room with a police officer on both sides making you look like you're a criminal, you're welcomed by someone who knows what to say, the tone of their voice, their body language, all of those things, and they take you into a quiet room to chat."

Ultimately Bricker says she would like to see trained crisis response workers responding to all calls involving those experiencing mental health issues with police, with the goal of avoiding a trip to the hospital all together.

"If they had picked Reid up on the street instead of taking him to the hospital and were able to have someone talk to him in his own apartment — where he felt safe — who knows, it might have been a completely different outcome," she said.

"Our emergency rooms are not equipped to deal with any mental health crisis, and yet we really don't have anywhere else to go."

AMM agrees with changes

While the province's plan to train hospital staff has come under fire from both the Manitoba Government General Employees' Union and the Manitoba Nurses Union, the Association of Manitoba Municipalities agrees with Bricker.

Chris Goertzen, who heads up the AMM, says the organization has been advocating for the change for years.

"I think the primary focus has to be for the patient, number one, to make sure that they're getting the appropriate care, but second of all that they're handed over and supervised by the appropriate people," he told CBC News.

"The police officers aren't always the best person to be doing that, there might be something better that they could be doing, and the patient could be getting as good or possibly even better supervision from qualified individuals who are trained to do that."

He said the issue of keeping police officers on the street is even more important for rural communities where that officer may be the only one working on a particular shift.

He said it's not uncommon for patients to be shipped "many hundreds of kilometres" to a site that can facilitate health care for someone with mental health care issues with a police escort.

Having trained staff at rural health centres will mean officers can release the patient and go back into the community, he said.

"We want to see that change for the patient and change for RCMP members and for the dollars that it's costing to do this," said Goertzen.

"We think that in the long run everybody is going to be better off with the changes that are proposed."

Union to raise issues with province

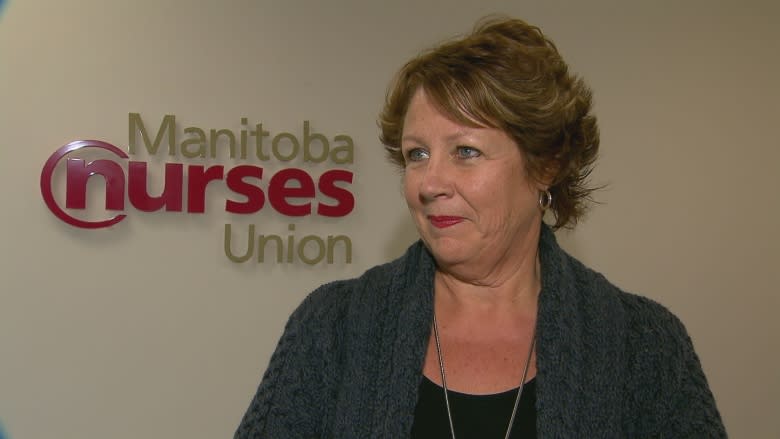

The Manitoba Nurses Union raised concerns about the bill when it was passed in 2016, and union president Sandi Mowat told CBC News this week she still believes it could add to the already significant workload of Manitoba health-care workers.

She said she gets the rationale behind reducing the hours police spend in hospitals, but she believes it should be security staff, not health-care workers, who take over that responsibility — provided security staff are granted the power to detain patients against their will, and that police remain if there's a concern about violence.

Mowat said the union will likely send a letter to the province next week detailing its concerns with the bill and reiterating long-standing requests for increased security staffing at Manitoba hospitals, some of which don't have guards on shift 24 hours a day.