Alberta hospitals prepare for potential ICU surge

Alberta hospitals are preparing to double-bunk critically ill patients, revamp operating and recovery rooms and reassign staff to treat an expected surge of COVID-19 patients destined for intensive care units.

The measures are so far beyond the normal standards, it shows that Alberta is preparing for a crisis, says a long-time critical care doctor.

"This is something that would only be carried out if there's a concern that we're going to get something close to what would be a disaster situation, or something that you would prepare for in a war," said Dr. Noel Gibney, referring to double-bunking ICU patients in a room designed for one.

As Alberta hit a new record of 96 COVID-19 patients in ICUs on Monday, it also reached another ominous landmark — a record number of new daily cases, at 1,733.

COVID's presence in Alberta ICUs has more than tripled during the last month. On Oct. 30, 24 people were critically ill with an infection.

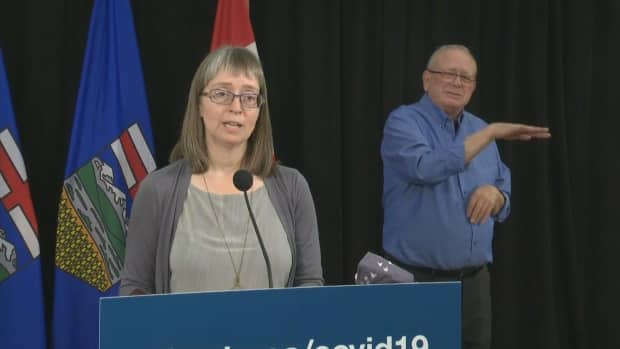

Provincial chief medical officer of health Dr. Deena Hinshaw said the data show Alberta is not yet at its peak of hospitalizations or patients critically sick with COVID.

"We do need to make sure we're bending the curve early enough that we never get to that point where we don't have capacity to care for everyone," she said at her daily media briefing.

Hospitals across the province are working to dedicate 2,200 beds for COVID patients, as they did last spring, Premier Jason Kenney said in the legislature.

"Let us hope it is not necessary," Kenney said. "And ultimately, that's up to Albertans to respond positively to both the restrictions and guidelines articulated by the government last week."

He also said the government will release data within days showing the projected impact of the pandemic on Alberta's health-care system.

The effort to ramp up ICUs

Dr. David Zygun, medical director for the Edmonton zone with Alberta Health Services, said hospitals can and will handle the growing caseloads of people sick with the potentially fatal strain of coronavirus.

The goal is to add more than 250 general ICU beds within weeks, bringing the provincial total to 425, up from the previous 173.

To do it will require some "unconventional" moves, he said.

The University of Alberta's hospital's ICU is already accommodating two COVID patients in a room designed for one, a practice AHS calls "cohorting."

Spokesperson Kerry Williamson said in an email the practice is not happening in other hospitals yet, but the measure is part of pandemic adaptation plans to meet increasing demand.

The Misericordia Hospital in west Edmonton has moved their ICU to their cardiac care unit to allow for better isolation of patients, he said.

The Grey Nuns Hospital in Mill Woods has moved its cardiac care unit to a different part of the hospital building to allow more space for the ICU, he said.

Although Calgary ICUs were over capacity on Monday, Edmonton ICUs had about 18 spare beds at last count.

AHS director Zygun said hospital staff are trying to proactively discharge hospital patients, move stable patients to less taxed facilities, open decommissioned space in buildings and reduce non-urgent surgeries to prepare for an influx.

To make space in intensive care, they're also postponing surgeries that aren't urgent or emergencies and staffing previously unused beds, he said.

If ICU and cardiac care beds are full, staff will then turn convert operating theatres and recovery rooms to temporary ICUs, Zygun said.

"Obviously, the space is not ideal, but certainly we feel that we can manage it safely," he said.

Gathering adequately trained staff to care for so many critically ill patients is one of the key challenges AHS faces, he said.

They turn first to people who recently retired or transferred away from jobs in the ICU. AHS has also proactively trained some employees who work in related areas, such as emergency and in operating rooms or recovery units. Those professionals would be matched with teams of experienced ICU employees, he said.

Staffing scramble, cramped spaces

But Dr. Darren Markland, an intensive care physician at Edmonton's Royal Alexandra Hospital, says it's not as simple as teaching professionals new skills.

Critically ill patients are complex and demanding, and staff are continually making judgment calls.

ICUs have never operated in the way the contingency plans are suggesting, he said.

"It's going to be a challenge, and the first couple weeks that we transition will have unfortunate consequences as we're learning how to do this model," he said.

He repeated a previous call for a lockdown to take pressure off hospitals.

"Waiting to see if these things work is a liability," he said.

Gibney likened managing a critically ill patient to flying a jumbo jet 24 hours a day.

ICU nurses typically train for six months and spend a couple of years on a unit before they feel confident, he said.

He said it will also be difficult to give patients the best possible care if they are cramped for space.

"They're not doing everything they can," Gibney said. "They still have restaurants open. You can still go to the casino tonight and play the slots and have a few drinks. Go to the bar. To have those things open while the hospital is preparing for a disaster situation is madness."