The opioid crisis is 'a unique product' of U.S. health care, paper argues

A working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) argues that the decades-long U.S. opioid crisis is “a unique product of specific policies and features of the U.S. health care market” that remain in effect.

“Without the opioid epidemic, American life expectancy would not have declined in recent years,” the paper stated. “In turn, the epidemic was sparked by the development and marketing of a new generation of prescription opioids and provider behavior [that] is still helping to drive it.”

In December 1995, the FDA approved a new opioid known as Oxycodone. Subsequently, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), “pharmaceutical companies reassured the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers, and health care providers began to prescribe them at greater rates.” A blizzard of prescriptions followed.

An estimated 21-29% of patients who are prescribed opioids for chronic pain end up misusing them, according to NIDA, while 8-12% develop an opioid use disorder.

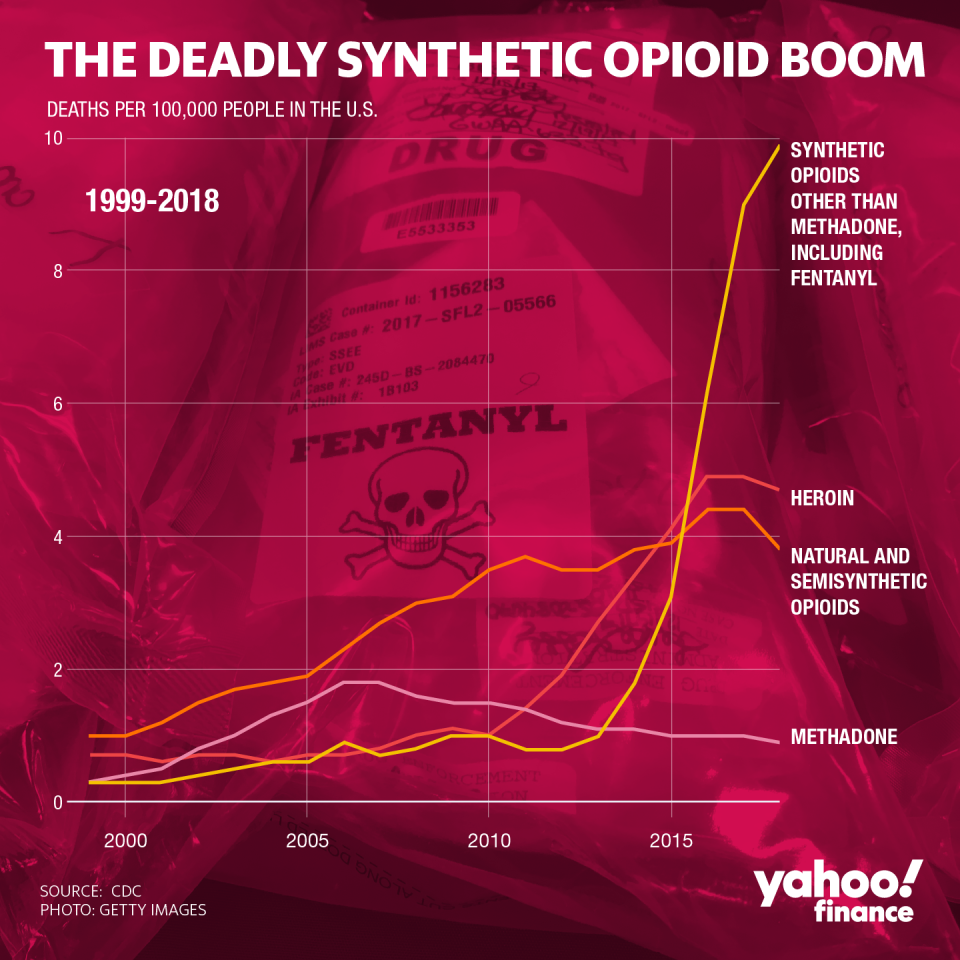

Tens of millions of Americans became addicted to prescription opioids and tens of thousands died of overdoes in the two decades that followed. In recent years, the overdose crisis accelerated after synthetic opioids like fentanyl began flooding the U.S.

‘A lot of the problem has to do with regulation’

The pharmaceutical industry’s opportunism — enabled by the backing of politicians and federal regulators — along with the emerging medical consensus that opioids were highly effective for pain management, led to opioids taking hold in American society.

Furthermore, money pouring in from Big Pharma and a green light from D.C. provided American doctors with a financial incentive to prescribe more opioids.

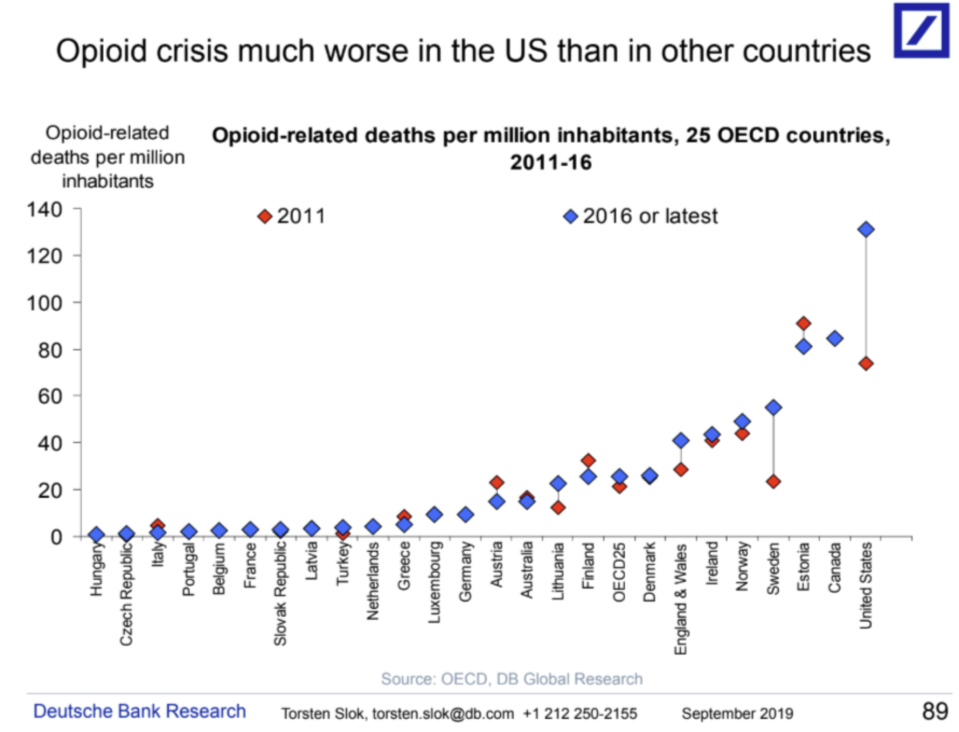

“People have blamed all sorts of things, heroin from Mexico and fentanyl from China and economic decline and so on and so forth,” Dr. Janet Currie, a professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University and one of the co-authors of the paper, told Yahoo Finance. “But really the issue is that a whole lot of people got addicted because they were prescribed pain medications which aren’t prescribed in the same way in other countries. They’re much more controlled.”

Opioids are prescribed and abused in the U.S. at a significantly higher rate than any other country.

“If you recognize that a lot of the problem has to do with regulation... most other countries, when they do allow opioid prescription, they don’t know how high doses of opioid prescriptions are but we do,” Currie said. “Most other countries don’t allow advertising medications direct-to-consumers but we do. There’s a whole list of things like that which have made things worse.”

‘The economic impact is also quite substantial’

Some research indicates a strong correlation between workforce participation and overdose rates. And last year, while testifying before the House Financial Services Committee, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell spoke of adverse effects on the workforce.

“An extraordinary number of people are taking opioids in one form or another and it weighs on labor force participation,” Powell said. “It’s a national crisis, really. The humanitarian crisis of it is completely compelling but the economic impact is also quite substantial.”

U.S. states are currently claiming that the crisis will cost the U.S. economy $2.15 trillion by 2040.

The NBER paper downplayed the labor supply aspect, stating that “there is little relationship between the opioid crisis and contemporaneous measures of labor market opportunity. ... Instead, we argue that there are specific policies and features of the U.S. health care market that led to the current crisis.”

David Powell, a senior economist at the RAND Corporation, agreed that increased access to opioids over time is the “main driver” of the opioid crisis but argued the labor participation aspect is important as well.

“The relationship between opioid access and labor supply merits a lot of attention,” Powell told Yahoo Finance. “First, there’s concern that the opioid crisis is negatively affecting labor force participation rates. While we rightfully often discuss the opioid crisis in terms of overdose deaths, it is important to understand its broader effects such as labor supply.”

Currie described the correlation between opioid overdose rates and labor force participation as “one of those urban myths,” arguing that “the relationship between labor force participation and opioid use is actually very weak.”

Opioid addiction has spread into both urban and rural communities across the nation. And although rates of overdose deaths are higher in urban areas than in rural areas, the most recent scourge in opioid deaths hit some rural areas particularly hard.

In a survey conducted by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), “when asked to identify the overall biggest problem facing their local community... 25% of rural adults identified opioid or other drug addiction or abuse, and 21% of rural adults reported economic concerns, including availability of jobs, poverty, businesses closing, cost of living, and low wages.”

‘We restrict the treatment and make it really difficult for people’

Ironically, regulation related to opioid addiction treatment in America is actually much more stringent than the policies and procedures that fueled the opioid crisis.

There is a ton of red tape related to medication-assisted treatment (MAT), defined as “the use of FDA-approved medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies’ to treat substance use disorders.

“Any doctor can write a prescription for opioids but to write prescriptions for people to get medication-assisted treatment, they have to have a special license,” Currie said. “Then the number of people they can treat is restricted. So we restrict the treatment and make it really difficult for people to get treatment once they’re addicted, and then we make it really easy for them to get addicted. And then we wonder why we have this big problem.”

Potentially adding to the misery, the ongoing coronavirus crisis could make treatment even more difficult.

“The coronavirus pandemic threatens to make the opioid crisis substantially worse by hindering access to effective opioid use disorder treatment and increasing risks of addiction relapse and overdose,” Rebecca Haffajee, policy researcher at the RAND Corporation and professor at University of Michigan School of Public Health, previously told Yahoo Finance.

Haffajee co-authored a journal article for the Annals of Internal Medicine that detailed the specific effects of the pandemic on those seeking treatment for opioid use disorder.

“Although the pandemic threatens everyone, it is a particularly grave risk to the millions of Americans with opioid use disorder, who — already vulnerable and marginalized — are heavily dependent on face-to-face health care delivery,” the paper stated. “Rapid and coordinated action on the part of clinicians and policymakers is required if these threats are to be mitigated.”

Adriana is a reporter and editor for Yahoo Finance who covers politics and health care policy. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

READ MORE:

Coronavirus pandemic 'threatens to make the opioid crisis substantially worse'

Expert: America's 'legacy of racism' led to a broken drug treatment system

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.