Anne Enright: ‘A lot of bad things happen to women in books. Really a lot’

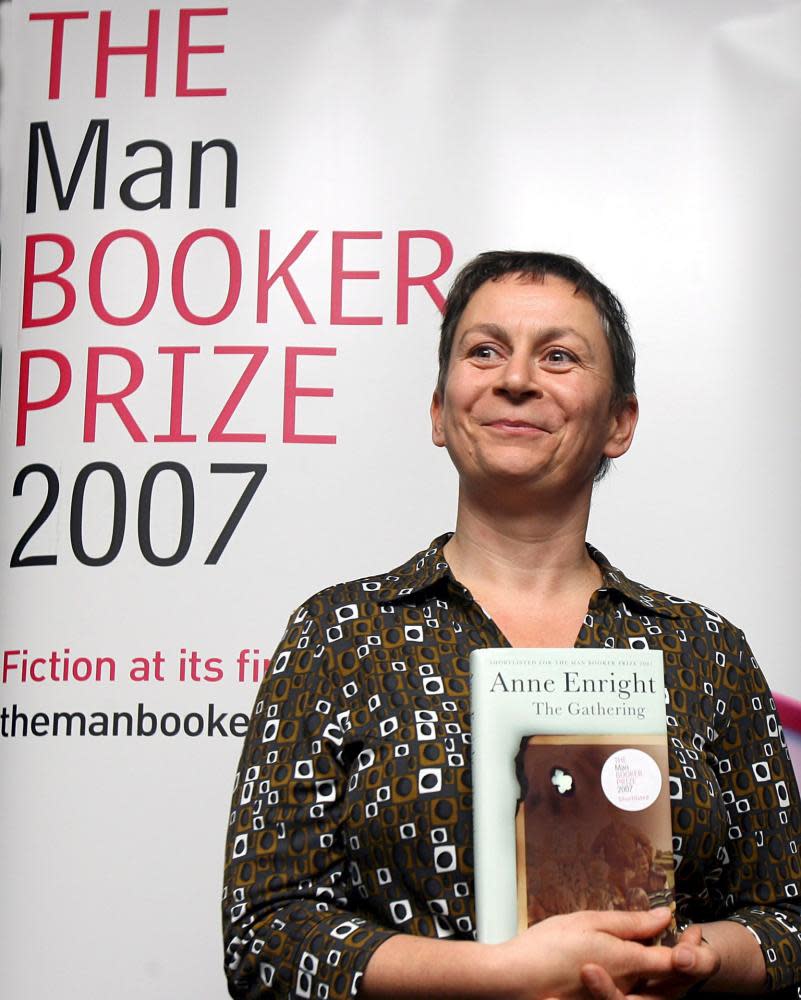

When Anne Enright began writing her latest novel Actress in 2016, a story of the dark side of showbusiness with a full cast of sleazebags and sexual predators, she felt that she “was breaking some kind of news”. Then came the Harvey Weinstein scandal. Ever since her 2007 Booker-winning novel The Gathering, which touched on sexual abuse in Ireland, she “has been interested in things that are barely spoken or taboo”. But now, “what went on in Hollywood” was finally being talked about. “It is really interesting how the tide rises,” she says. “I was one of the many boats on this rising tide.”

In Katherine O’Dell, her fictional fallen star of stage and screen, all “mad green eyes”, cigarettes and secret shame, Enright has created a heroine as irresistible to the reader as to her audiences and hangers-on, “a great Irish Disaster”. Narrated by O’Dell’s daughter, a writer, looking back to Ireland in the 1970s, Actress covers familiar Enright territory: tricky mothers, a dark period in her country’s history, sex and marriage (the narrator’s domestic contentment is set against the violence and shabby romances of her mother’s past). Enright had been promising to write her “theatre book” for years, drawn to “that nostalgia, that slightly tawdry, slightly worn-out, hopeful, foolish thing. I always loved all of that.” She was a professional actor “for at least six months” after leaving college. “I loved backstage.” She wanted to capture what she calls “the moment of glamour”, which is also a “pang of loss. The moment you see that something is beautiful is the moment it starts to recede from you, or you see that you don’t have it. It’s somehow unreachable.”

Enright, who once compared her relationship to the Irish literary scene to a salad – “I’m always on the side” – is now at its heart: in 2015 she was appointed the nation’s inaugural laureate for fiction. She has become a byword for contemporary Irish literary fiction at its finest: “I’m not saying I’m Anne Enright,” popular novelist Cecelia Aherne quipped in an interview. When we meet she is fresh from recording Desert Island Discs (which included a mix of Johnny Cash, Leonard Cohen and Mozart). With her puckish crop and big eyes, she resembles a more mischievous Iris Murdoch. She says she rejected “the chilly uplands of modernism, which is a place I might have gone” for “the connected stuff” of love and relationships. And as you’d expect from her fiction, she is warm, irreverent and a little bit spiky, her conversation a tumble of wry observations, perfect metaphors and swearing.

There was always some horrible little misogynist that they could roll out to take you down

When she was appointed as laureate, she used the platform to get stuck into the “astonishing gender imbalance” in Irish literature: “There was always some horrible little misogynist that they could roll out to take you down.” She was fed up with what she saw as “a very real sneering about women’s work, a reluctance for it to be treated as equal”, which she had experienced in her own career, from the critical reception of her early work – “women were quirky, men were modernist” – to grumbling from certain male writers after she won the Booker: “It took me a while to figure out what was going on in a couple of cases,” she revealed teasingly on the radio. Today, she says, “you aren’t going to get the crusty old bastards to cheer up and like you. That’s just their problem.”

But she’s done with being angry. “The whole gender thing is an energy-sapping event,” she says. “I’m on the other side of it now. I think something happens in middle age when you’re not that interested in impressing guys any more.” It’s hard to imagine Enright ever giving a damn what anyone else thought. “I have actually been interested in ‘competing’,” she says of her position as a rare female voice in a generation that included Colm Tóibín and Sebastian Barry. But, with the rise of Irish writers such as Eimear McBride, Sally Rooney and Anna Burns, the literary world is less of a lonely place for women. One of the most interesting things about “the Irish moment” is the diversity of voices. “The themes are there, but it is like different languages.” And she is very excited about “a great gang of younger male writers in Ireland, who are not very backlashy, but they are very there. There’s no absence of talent.”

“It’s great to have Ireland to write about,” she says drily. “It’s a great resource.” Her fiction has been unafraid to engage with its past – from abuse in The Gathering to the fall of the Celtic tiger in The Forgotten Waltz. For the record, Actress includes her “first dodgy priest”. The priest in The Gathering “just felt like one. I took the atmosphere.” And she has always resisted having “a pop” at the Catholic church, “partly because it’s like kicking a bus, and anyway the bus wasn’t going anywhere”. And this is the first time she has touched on the Troubles. “There have been iconic female figures in Ireland who are more enthusiastic than not about the Republican movement,” she says of O’Dell’s fondness for IRA men and nationalism. Growing up in the south (“bombs in Dublin were utterly close”), “the shift of sympathy away from violence” was vital to her sense of herself as Irish. One of the terrors of Brexit, she says, “is that when you see someone like Boris yomping about, you think they could make the same mistakes that were made in the early 70s in Northern Ireland because they have no sense of what the place is.”

Enright was the youngest of five – “two brothers, two sisters and me” – all of them brainy. (She had read all of the children’s section in the local library by the age of seven and James Joyce’s Ulysses at 14.) The “nostalgia for the adored mother” in Actress is inspired by her own mother’s feelings towards her grandmother, a university-educated woman who was widowed with four children. “We idealise our mums, particularly the children of single mothers,” she says.

“I sometimes feel a little resentful that the Irish have to have mothers for everyone else,” she jokes. “Irish writers aren’t afraid to admit it’s a big deal having a mother.” So much so that for many years, they were considered “too sacred, or too difficult” to be put into novels, “although it feels like they are everywhere”. For Enright this paradox has always been the other way round. Once asked why there are no fathers in her fiction, she thought, “Well, I find them unapproachably interesting. Clearly. Or interestingly unapproachable.” And while Actress might appear to be a novel about mothers, “in fact, there’s an awful lot of hidden stuff about the father, whoever that is.” The loss of her own father, “a quiet man, gentle and smart”, who died just as she was beginning the novel, is “in amber, trapped in some of the paragraphs”. His death, coinciding with the election of Donald Trump in the US, provoked a crisis of confidence in male authority figures for the author: “I lost a wonderful man from my life while the world gained a terrible one,” she wrote.

The truth of my life has been that I must now announce myself to myself as having been happily married, whatever that is. Why does no one write that?

“I don’t do plottedness,” Enright says. “I do stories, I do slow recognition.” She also “likes messing around a little bit”. The narrator of Actress, Norah, writes novels “about life and love” in which the characters “just realise things and feel a little sad”. Norah is in her late 50s when we first meet her and lives in the Irish seaside town of Bray with her husband and two teenage children – just like Enright. “I’m not hiding it under a rock,” she admits, laughing. “But it’s not me either. You turn your life inside out or something.” There is one big difference: unlike Enright’s characters, Norah’s “rarely have sex and they certainly do not attack each other”. “Oh well that’s just a big joke!” Enright hoots. “What’s a lot of sex? [My characters] are not doing it day in day out. It might be a Tuesday thing. But they certainly know where they are in these matters.”

More seriously, she wanted the novel “to reclaim ideas of agency in desire”, something she has been doing throughout her fiction, along with other female Irish writers from Edna O’Brien to Rooney. “To push back against the idea that sex is a terrible thing, horrible and rapine and always somehow disappointing and wrong. It’s an idea from the misogynistic patriarchy that returns and returns in more modern iterations. A lot of bad things happen to women in books. Really a lot.”

Having written about adultery in The Forgotten Waltz, she also wanted this novel “to be a conversation about marriage”, to make a monogamous long-term relationship interesting. “The truth of my life has been that I must now announce myself to myself as having been happily married, whatever that is,” Enright says. “Why does no one write that?” She is at her merciless best on the daily intimacies and irritations of married life. “I liked the shifting sense of difficulty and accommodation and attachment. And that inescapability of it all,” she explains. “There’s an amount that is written about love and sex that seems to me somehow partial. So I wanted to give a more complete picture.”

The novel’s second love story, as important as that between mother and daughter, is “the long-suffering husband of the writer”, the unseen “you” to whom the story is addressed. Enright has been with her husband Martin Murphy (she refers to him by his full name) “for ever” – “the love of my life”, as she said in her Booker acceptance speech. They met when she signed up for the drama society in freshers’ week at Trinity College and he was the director: “Bingo!” he wrote on her audition notes. But they didn’t get married until after Enright’s breakdown (“I know you aren’t allowed to ask me about my breakdown”, she teases) after working in TV for many years: “Television producers have nervous breakdowns the way old ladies have potted plants”, she wrote in an essay in her collection Making Babies. She was sent to “a home for the bewildered, a very middle-class sort of place”, she says now. “There were women crying, sometimes in very lovely pyjamas, white satin.” She is bored with the “I used to be nervously broken down but then I won the Booker prize” narrative of early interviews. “It is much more interesting than that,” she says of the discussion around mental health. “It’s such a day-to-day thing.” But it did force her to make some decisions: to leave broadcasting, “to marry the man” and, most importantly, to become a full-time writer.

She enrolled on the creative writing course at the University of East Anglia, with Angela Carter as her tutor (Actress could be her answer to Carter’s Wise Children), where she sat up all night and “lost” words. There followed a decade “full of anxiety” in which she “worked very badly and hard at the same time. I wasn’t sensible at all.” She abandoned her great novel (spanning three centuries in three languages, no less) for short stories and learnt “to fail better” until something finally shifted. “There’s nothing special about thinking you are no good,” she says now, a piece of advice that should be pinned above the desk of every aspiring writer.

With Actress she had a rare period of knowing the book was in her “possession. All I had to do was write it, bring it up to its best self. I have seldom been as happy.” For her, a novel (when it is going well) is a place of safety, an escape from the world: “It’s like your own personal swimming pool, you can go there any time.” As well as swimming, which she does in the sea at Bray, she is a keen yogi – “I do the moves. I don’t jump about the place.” Writing, like yoga, is “a practice, you turn up on the mat”, she says. “It’s not about theory, it’s about putting words on the page and then going back day after day. It’s a life.”

• Actress is published by Jonathan Cape (RRP £16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15.