Antarctic sea ice melts to a new record low for the second year straight

For the second year in a row, summer sea ice around Antarctica has reached a new record low extent.

Update March 8, 2023: Antarctic Sea Ice Extent reached its lowest extent for the year on Feb. 21, at just 1.788 million square kilometres. This represents a new record low minimum, 136,000 square kilometres below the previous record of 1.924 million sq km set roughly one year before, on Feb. 25, 2022.

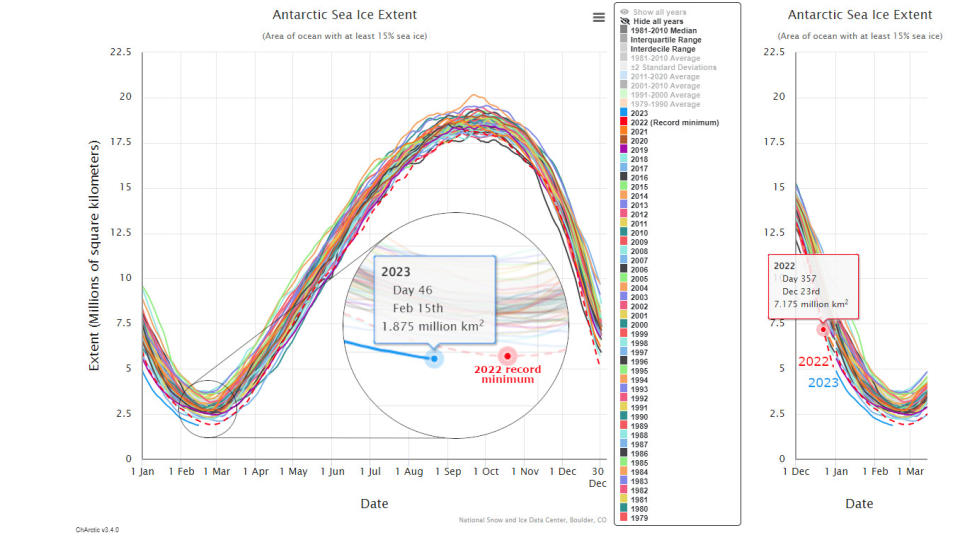

The Charctic graph of Antarctic sea ice extent reveals the new record low reached on Feb. 21, 2023. The inset zoomed view shows this in greater detail. Credits: NSIDC, inset added by author.

"Antarctic sea ice may be reversing course," the NSIDC stated in their March 2 update. "Until recently, there was a weak overall upward trend in Antarctic sea ice extent, but with some parts of the Antarctic sea ice exhibiting strong positive trends in extent and other areas exhibiting strong negative trends. According to colleagues at Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO Australia), this pattern is changing. Over the past decade, there is less regional variability. Patterns of sea ice extent variations, high or low, have become more uniform around the continent. This has contributed to the lower Antarctic sea ice extents that have been observed since 2016."

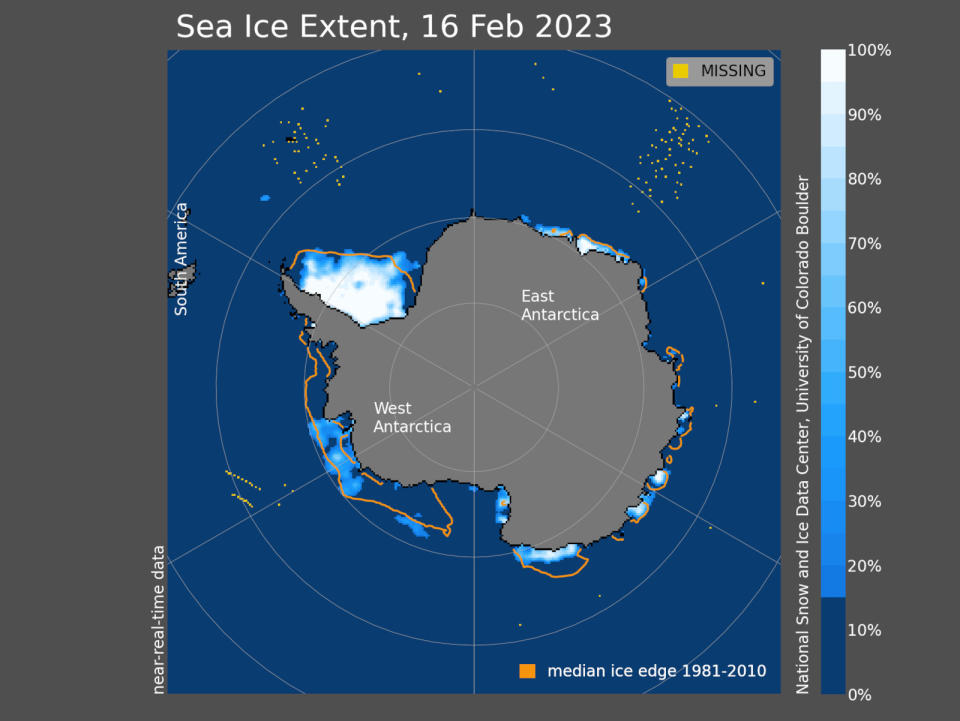

This map of Antarctic sea ice from February 21, 2023 plots the ice extent (compared to the 1981-2010 average, shown by the orange line), and also the concentration of the ice, revealing those regions of ice extent that are very sparse. Credit: NSIDC

The original story, published on Feb. 17, 2023, continues below.

In February 2022, satellites recorded the lowest Antarctic summer sea ice extent ever seen.

"For the first time since the satellite record began in 1979, extent fell below two million square kilometres, reaching a minimum extent of 1.92 million square kilometres on Feb. 25,” said the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the time.

Now, less than one year later, the extent has not only fallen below two million sq km again, it has also broken 2022’s record minimum.

As of Feb. 14, 2023, the extent dwindled to less than 1.9 million sq km.

This graph shows Antarctic sea ice extent from 1979-2022, and so far in 2023. Inset is a zoomed view of the late-summer minimums, comparing the 1.875 million sq km extent on Feb. 15, 2023, to the previous record low on Feb. 25, 2022 (1.92 million sq km). The panel to the right shows how the sea ice extent had already dropped below historic low levels back on Dec. 23, 2022, and persisted at low levels until now. (NSIDC/Scott Sutherland)

“This year represents only the second year that Antarctic extent has fallen below two million square kilometres,” the NSIDC stated in their Feb. 13 update.

Based on the usual pattern of melting, we haven’t even seen the new final record low yet.

“With a couple more weeks likely left in the melt season, the extent is expected to drop further before reaching its annual minimum,” the NSIDC said.

As shown in the graph above, the sea ice extent around Antarctica fell to below previous record low levels in December, and this trend continued throughout January and February so far.

NSIDC scientists attribute this to weather conditions, specifically stronger-than-normal westerly winds and a strong low-pressure system over the Amundsen Sea, which resulted in warmer weather impinging on a large region of West Antarctica.

“Even as somebody who’s been looking at these changing systems for a few decades, I was taken aback by what I saw, by the degree of warming that I saw,” Carlos Moffat, a University of Delaware oceanographer, told Inside Climate News.

According to ICN, Moffat was part of a recent expedition along the coast of West Antarctica, where the researchers noted “an eerily warm ocean and record-low sea ice coverage.”

“We don’t know how long this is going to last,” Moffat said. “We don’t fully understand the consequences of this kind of event, but this looks like an extraordinary marine heat wave.”

The extent and concentration of Antarctic sea ice on Feb. 16, 2023, compared to the 30-year average extent (yellow line). While sea ice along East Antarctica and in the Weddell Sea is near average, there is hardly any ice along West Antarctica compared to normal. (NSIDC)

Coastal protections lost

One benefit to having more sea ice around Antarctica is that it tends to act as a buffer for coastal glaciers, keeping warmer ocean waters farther out to sea and calming the waves at the edges of the ice.

According to the NSIDC, with this record low for sea ice extent, “much of the Antarctic coast is ice free, exposing the ice shelves that fringe the ice sheet to wave action and warmer conditions.”

One of the glaciers left exposed by this lack of ice is Thwaites, West Antarctica’s aptly named Doomsday Glacier.

Researchers have shown that Thwaites is rapidly retreating, by roughly a kilometre each year, and one estimate revealed that the entire glacier could collapse within five years.

These maps show the location of Thwaites Glacier, pinned between the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Amundsen Sea. (NASA)

With the coast more exposed to warm ocean waters, glaciers like Thwaites are even more at risk. New research examined the impacts these warmer waters can have on Thwaites, specifically, by sending a submersible robot underneath the glacier to observe how the ice is being affected from below.

“These new ways of observing the glacier allow us to understand that it’s not just how much melting is happening, but how and where it is happening that matters in these very warm parts of Antarctica,” Britney Schmidt, lead author of the paper from Cornell University, told the Cornell Chronicle. “We see crevasses, and probably terraces, across warming glaciers like Thwaites. Warm water is getting into the cracks, helping wear down the glacier at its weakest points.”

Watch below: Underwater robot helps explain Antarctic glacier’s retreat

If Thwaites were to completely collapse, the direct effect would be to raise global sea levels by more than 60 centimetres. More importantly, though, the glacier is currently holding back a large section of the West Antarctic ice sheet. Thus, the collapse of Thwaites could quickly lead to the destabilization of the ice sheet behind it, which could raise ocean levels by a further three metres or more.

A new alarming trend?

Sea ice around Antarctica goes through a seasonal cycle of growth and melt. The ice reaches a maximum extent in September, during late southern winter. The melt season then begins, resulting in a minimum extent in late February or early March, during late southern summer. The curve the ice extent traces varies from year to year, based on weather conditions. However, there have been some trends seen over the past few decades.

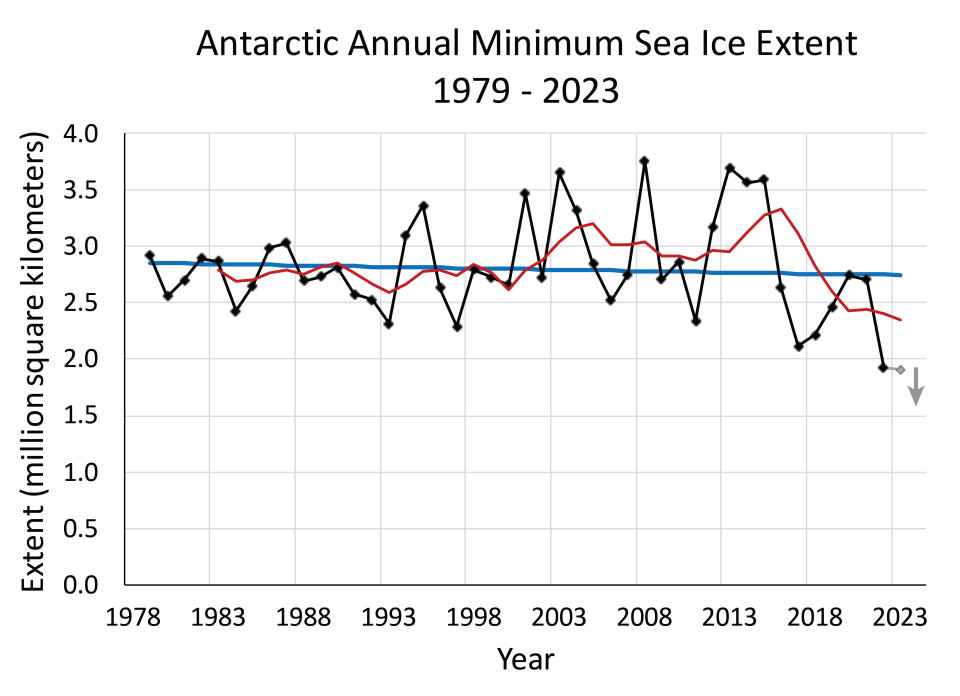

Each year’s minimum Antarctic sea ice extent is plotted here, from 1979 through 2022. 2023’s current lowest point is the smallest extent seen since record-keeping began. (NSIDC)

Up until the early 1990s, there was a slight but noticeable downward trend. Starting in the mid-1990s though Antarctic sea ice extent began to increase overall — both the winter maximums and the summer minimums. But over the past eight years this trend appears to have reversed.

Experts mainly attribute the increase from the 1990s to the mid-2010s to two factors: more ice was forming due to an increase in meltwater pouring into the oceans from ice on land, and stronger winds were spreading the mass of sea ice farther out into the ocean. This trend was supported by a strong southern polar vortex flowing above Antarctica, coupled with a strong ocean current circulating around the edges of the Southern Ocean, both of which sheltered the region from much of the impacts of climate change felt in the rest of the world.

However, this trend was not expected to last. Inevitably, increasing ocean and air temperatures would take their toll, causing sea ice extent to diminish. Since 2016, it seems we are now seeing this reversal.

Thumbnail image: An iceberg sits still on a calm day in Antarctica. (David Merron Photography/Getty)