'They're all good children': How school staff try to coax Natuashish kids back to class

Derrick Fewer, the principal at the Mushuau Innu Natuashish School, starts each day standing at the building's front door, greeting students and ushering them in.

Classes technically start at 9 a.m., but Fewer knows he has to be patient. Some of the older kids in the remote First Nation reserve of Natuashish, N.L., have to babysit siblings while their parents work out of town, so some are going to be late.

Others may sleep in, so Fewer has to make some calls.

"We phone the children at home and oftentimes, the parent will get on the phone, and I say, 'No, I want to speak to your daughter, your son,'" Fewer said.

By speaking to the students directly, he hopes to keep them accountable — if they're not going to show up, they at least have to explain themselves.

It's the same reason Fewer stands at the front door every morning: to keep track of who's coming and make sure students feel welcome as soon as they cross the threshold.

"They're all good children. I'm never going to be convinced of anything else," he said. "But they have their own challenges in life."

Struggle with language, attendance

Fewer will be the first to admit that this is not like other schools.

According to a 2014 report prepared for the Innu school board in Labrador, students in Natuashish received modified programming compared with students elsewhere in the province.

No high school classes completed the work set out in the annual curriculum, and only about half of high school students showed up for class regularly.

This year, 459 students are registered at the K-12 school, but only 367 attend regularly.

Fewer says staff are working hard to keep more students in class. But the challenges facing young people in Natuashish, who make up half the town's population of 936, are the kind that keep them out of school.

For starters, there is easy access to alcohol and drugs, as well as grief over recent suicides.

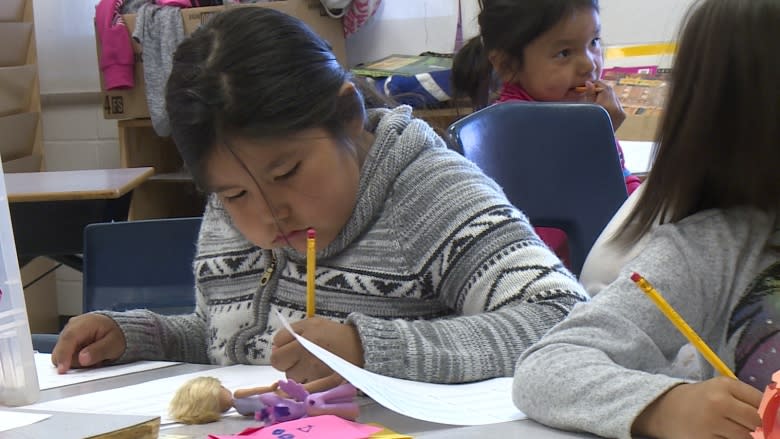

Fewer says the kids also have challenges with language. Almost every student here speaks Innu-aimun as their first language, but they study and take standardized tests in English.

"They do have to memorize the words," Fewer said, describing the way children learn.

"A lot of our Grade 2 kids are reading at a Grade 4 level. But they don't know what they're reading. That's the English as a second language."

Innu role models lead the way

This year, five Grade 12 students will get their diplomas. The record for a single year is nine.

Tyler Rich, 18, was supposed to graduate, but he'll have to wait until next year.

"I didn't have enough credits," he explained, but he isn't giving up. Rich has a plan to go to college in Ontario when he graduates.

"I want to do media arts," Rich said, adding that he can already see himself in a new town.

All around the school, students see the proof that education pays off.

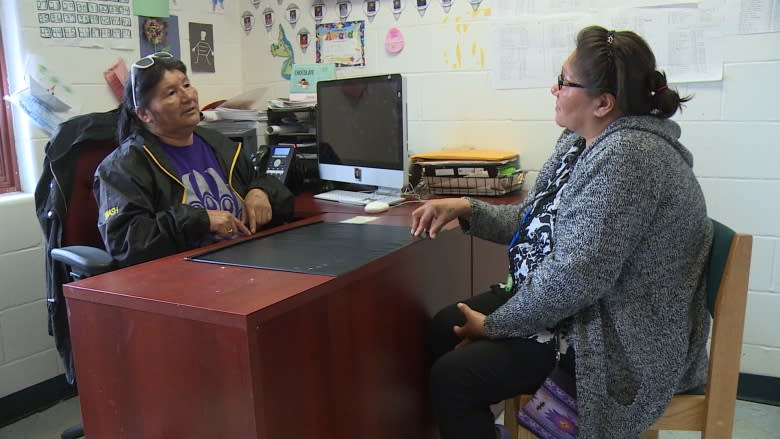

The two vice-principals, Penash Rich and Nora Pasteen, are Innu. There's an Innu classroom assistant with every teacher and Innu support staff, too. They're translators, counsellors and role models.

Rich and Pasteen grew up in now-abandoned Davis Inlet, an island community 18 kilometres down the coast notorious for substandard living conditions, where the school once burned to the ground. The Innu left Davis Inlet and moved to Natuashish in 2002.

Pasteen is as much of a coach to her students as a vice-principal.

She tells them, "You gotta really work hard for this. For you to move on, for Grade 12. You got to study, study, study. Come to school every day, every day, every day," she said.

It's advice she follows, too. She herself is just five credits away from a bachelor's degree in education.

"Every year, a lot of kids are graduating. It's a big difference [from] back in Davis," said Pasteen, who started working as a janitor at the school in Davis Inlet.

"Sometimes kids get really frustrated, but we talk to them, encourage them to come. It's pretty much good here, and I hope they'll keep it up."

Lots of distractions

For some young people, keeping it up is easier said than done.

Javaron Gregoire, 20, admitted that when it came to school, his heart wasn't in it.

"I dropped out," he said recently, leaning out the window of a pickup. He was on a break from his job as a garbage collector for the band council.

Gregoire blamed his lack of interest in school on "distractions. Lots of them, like doing drugs, drinking alcohol and staying up late at night."

Gregoire said even though alcohol is outlawed in Natuashish, it's easy to come by. A 750-millilitre bottle sells for upwards of $300, but kids still manage to get their hands on it.

He is now two months sober, but said he's too old to register again for high school.

"I used to go to school sometimes, but I just hung out in the hallways, never listened to the teachers," he said. "It's too late for me to go back."

'It's an improvement'

Despite some obvious challenges, Fewer has big goals for Mushuau Innu Natuashish School. He'd like to implement a mature-student program so that people like Gregoire don't miss the chance to graduate.

While that's in the works, Fewer is also trying to coax other teens back to school — before it's too late.

Of the 59 students at Mushuau Innu who are eligible for high school, about 40 are coming to class regularly, he said.

"Last year, it was around 18. So that is a big increase. It's an improvement and it's good — but I want it to be 59."