I'm a Dreamer Who Married the American I Love — Here's What DACA Means to Us

On the morning of November 9, 2016, I peeled myself out of bed after getting just three hours of sleep. I’d fired off a frantic chain of text messages the night before, and my boyfriend, Henry*, had finally responded: “I guess we’re just going to have to get married then.”

I let out a sigh. It wasn’t a romantic proposal, but that’s how our journey to marriage started.

Henry and I first met two years earlier, on a sticky city summer night, the kind when even the rush of the subway entering the station provides a millisecond of relief from the relentless heat.

A mutual friend was visiting the city from out of town, and he invited a few people over to my apartment before we went out to meet other friends. Henry showed up at my door wearing a T-shirt with his brother’s face on it. Interesting choice. But he was easy to talk to, funny, and sweet. He was 23 and I was 24. When everyone started heading home, I invited him to stay at my place. We took the subway up to midtown, and on the walk home from the train, he danced on the sidewalks, eyes closed. What a weirdo, I thought.

If you told me the night we met that we would get married less than three years later, I would have laughed. But that’s what we did. And two weeks after our wedding, we moved in together. At 26, we both felt far too young to be married. While the romance is very much there, it wasn’t our choice of timeline. Yes, we chose to get married. But it's what happened on November 8, 2016 that pushed us into that choice.

Yes, we chose to get married. But it's what happened on November 8, 2016 that pushed us into that choice.

Henry had fallen asleep hours before the final results of the presidential election came in, but I couldn’t sleep. The stakes were high: Throughout her campaign, Hillary Clinton claimed that through her immigration reform, recipients of DACA (Deferred Action For Childhood Arrivals) would be protected from deportation. As a DACA recipient, I had high hopes for a Clinton victory. After fearing for my status for over a decade, I finally felt a glimmer of hope.

If you’re not familiar with DACA, it’s a 2012 policy directive introduced by the Obama administration that allows certain people who came to the U.S. as undocumented children to temporarily defer deportation, if they meet several guidelines. DACA recipients, who pay taxes, can stay in this country, work, study, and obtain driver's licenses lawfully. Obama issued the policy directive after the DREAM Act (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) came to a stalemate in Congress. Only an act of Congress would enable people who came to the U.S. as undocumented children a path to applying for green cards, but DACA — which had to be renewed every two years — provided a temporary respite from the threat of deportation.

My family immigrated from the Philippines when I was nine years old. My older brother and sister were going to college here and my parents wanted us all to be together. Plus, they knew my other siblings and I could also receive a better education here, so we made the move in 2001 with B-1 and B-2 business visas. We eventually switched to L-1 and L-2 visas for business expansion, which we renewed three times.

After tens of thousands of dollars spent and a handful of lawyers hired in an effort to gain permanent residency, we were denied. I lost my visa while I was in college, but luckily my school was a sanctuary campus and I didn’t have to reveal my status.

In 2012, when I was a sophomore in college, the announcement of DACA was life-changing. I applied before graduating in 2013, finally got on the program from 2014 to 2016, and then renewed it. After years of my family worrying about our status, I had officially been granted the opportunity to not only stay here, but to work.

Unfortunately for us, and for many of the 800,000 others who have renewed their DACA status since 2012, Donald Trump talked throughout his campaign about reversing Obama’s immigration policies. Now, he's announced his plan to do just that.

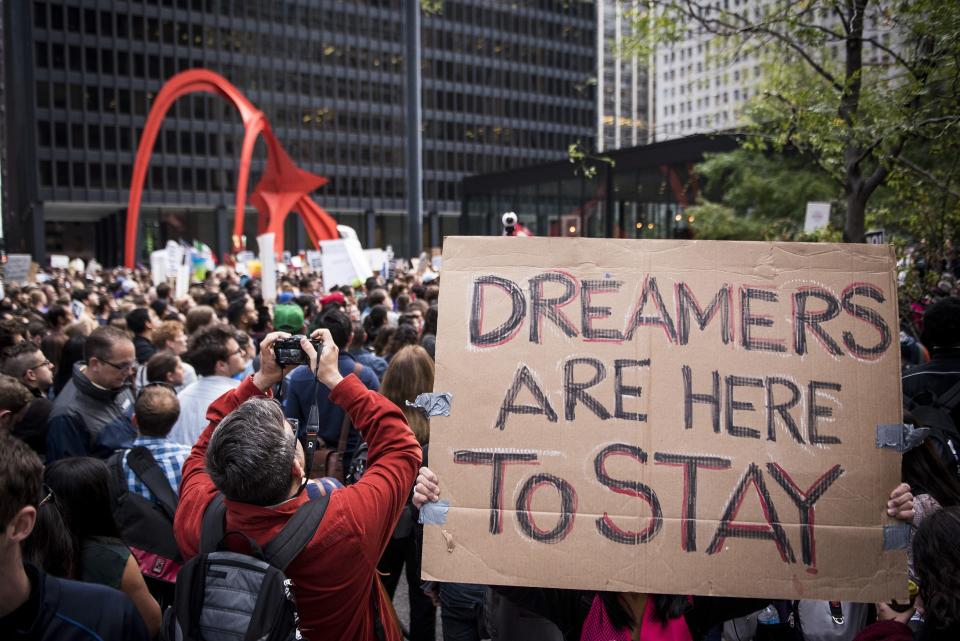

Demonstrators Protest After Trump Ends Deferred Action For Childhood Arrivals Program

Henry and I had talked for months leading up to the election about what we would do if Trump won. But it was always just talk: We were so confident Clinton would win, we couldn’t imagine what might happen if she didn’t. Just the summer before the election, we had an enormous fight outside of his apartment one night. He told me he didn’t believe in marriage, and I erupted. Not only did I view marriage as a commitment to the person I loved, it was my last option for applying for a green card — how could he not see that?

“If you believe in us having a relationship, you have to believe in marriage,” I fired back. “Either that, or we might have to move back to the Philippines.” For a long time, we never spoke of that fight, but after we got married, I asked him about it — and what had changed his mind. Henry answered, “I believe in whatever means necessary to have you stay in this country and be with me forever.”

I believe in whatever means necessary to have you stay in this country and be with me forever

After Trump’s inauguration, our decision seemed clear. In February, I emailed my lawyer that we were planning on getting married in May, and to my surprise, he emailed back urging us to get married as soon as possible. Two weeks later, we were married at the courthouse. We hadn’t even had time to move in together yet. In order to get a green card through marriage, you have to prove your marriage is legit — and part of that is living together. So we both broke our leases and started the daunting hunt for a shared apartment.

I wouldn’t change how things are right now. Henry and I are happy and comfortable in both our marriage and our new place, and really, nothing about the day-to-day of our relationship has changed. But when I look back on getting married, I see that I didn’t have the time or space to enjoy what should have been happy moments. They’re marred by the anxiety of paperwork and the feeling of rushing to get everything done. We knew we wanted to spend the rest of our lives together, but we didn’t know marriage would come so quickly. And instead of a day of celebration, our wedding day felt more like one step in the frantic process to file for a green card and prepare all of the documents I needed to apply for an apartment.

We’re still mentally catching up to all of the life changes that had to happen so quickly, and there’s a sadness that pops up at unexpected moments. I’m thrilled at the benefits that come from being married to a U.S. citizen. But I can’t help but feel robbed of the moving-in experience, engagement, and ceremony I envisioned having with Henry. Many couples have months and even years to savor each and every step of joining their lives together. Henry and I had two weeks.

In my ideal world, I would have waited until my 30s to get married. I wanted to pay off more of my student loans and feel on top of my finances, and I wanted to live on my own for the first time before I moved in with a partner. The past year has held more sleepless nights, anxious days, and feelings of alienation and loneliness than I could have imagined – which no one, regardless of their immigration status or the country they live in, should have to go through.

The past year has held more sleepless nights, anxious days, and feelings of alienation and loneliness than I could have imagined

Still, I’m thankful about how my story is playing out. I know that many of the 800,000 people currently on DACA don’t have the same opportunities and support as I do. Now that Trump is ending the policy directive, hundreds of thousands of people stand to lose its protections — meaning they may lose their jobs and possibly their residency. When I heard the news, I was relieved that Henry and I chose to get married when we did. But I am heartbroken for those who could lose everything — not just their jobs, but the lives they’ve built. For many, deportation means going back to a country you haven’t seen since you were a child, one you may not even remember. It means leaving your career, friends, and family behind. It means your dreams are ripped right out of your hands.

DACA changed my life. For as long as I can remember, all I wanted in life was to go to school and get a job. DACA allowed me to fulfill that dream. Yes, there were hurdles, both financial and logistical, but the work was all worth it. For Dreamers like me, attending school and attaining a job legally is an aspiration rather than an expectation, as it is for many people born in this country.

I’m here, and hopefully, I will continue to be. Nothing gives me more relief than knowing that after 16 years of trying to become a permanent resident, this goal is on the horizon. And while tying the knot with my husband didn’t happen in the way I dreamed, I’m grateful for our marriage and the chance to stay in this country — the country where I grew up, made friends, fell in love, and started my career. Henry and I have each other, and we have a future here. That’s more than most Dreamers can say with confidence right now. If you have a voice to speak up and fight for us, I ask you to use it. We need it now more than ever.

*Names have been changed.

Related: