'A remarkable battle that was largely forgotten': Hill 70 memorial set to open in France

A group huddles around a collection of large black-and-white portraits strewn across a table at the armoury in Kamloops, B.C.

Peering through magnifying glasses, they search for a specific face among the rows of troops dressed in identical uniforms.

They are looking for a soldier they never knew, who fought and died in a battle most have never heard of.

"It was a Chinese-Canadian kid from 100 years ago, volunteering to participate in a war," said Jack Gin, a philanthropist with a love of history. "I was astounded to learn of this Frederick Lee person."

Lee was one of only a few hundred Chinese Canadians who enlisted during the First World War.

While he fought at the famous battle of Vimy Ridge, his name recently surfaced because of research that was done to commemorate a much lesser known battle in northern France.

An unknown part of history

Around 100,000 Canadian soldiers — Lee included — fought at Hill 70.

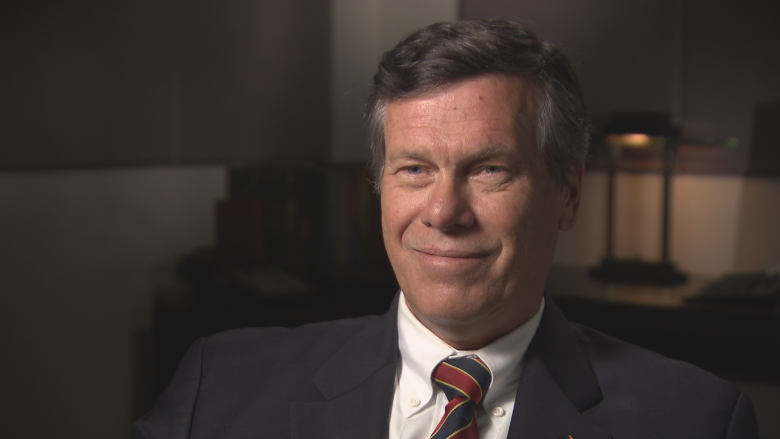

"It was a remarkable battle that was largely forgotten," said Mark Hutchings, chairman of the Hill 70 Memorial project.

Hutchings believes the battle, which took place four months after Vimy Ridge, deserves the same kind of reverence in Canadian history.

It was the first time Canadian forces were led by a Canadian commander.

The British asked Sir Arthur Currie to attack the Germans at the French town of Lens and create a diversion that would prevent them from moving troops into Belgium, where the Allies were planning a larger offensive.

Hutchings says Currie pushed to change plans after doing reconnaissance of the area.

"He went and had a look and said, oh, this would be a meat grinder, we would be doomed to fail the same way the French failed, the British failed," he said.

Currie believed that the Canadians should instead try attacking the higher ground north of Lens — an area that was named Hill 70 because it was 70 metres above sea level.

The British agreed, and as dawn broke on Aug. 15, 1917, the Canadian Corps launched its attack.

Battle for Hill 70

Within hours, they were able to gain the higher ground, and over the next 10 days the Germans launched 21 counterattacks.

It was a bloody battle, and a devastating loss for the Germans, Hutchings says: there were between 20,000 to 40,000 German casualties, "depending on which history you read."

On the Canadian side, 1,877 men were killed including 21-year-old Lee, who died on the sixth day of the battle. His name is etched on the Vimy Ridge memorial, and he is one of more than 11,000 Canadians who were killed in action in France and whose final resting place is unknown.

While the Canadian Corps' accomplishment at Vimy is a storied and celebrated part of Canada's history, the victory at Hill 70 is largely unknown.

Since 2012, a group of volunteers has been working to change that, and on August 22, the Hill 70 Memorial Park will open in France, one hundred years after the First World War battle.

The site is about 15 kilometres from the Vimy Ridge memorial and features a white limestone obelisk and a pathway marked with 1,877 maple leaves.

Gin and his group are fundraising to build another walkway which would wind to the top of the hill and be named after Frederick Lee.

"It would be symbolic," said Gin who has been helping to research Lee's story.

"I see Frederick Lee as a metaphor for the hard work and struggle for the early Chinese."

Wide-spread discrimination

Lee was born in Kamloops in 1895. Those researching his story have discovered that he was one of eight children in his family. His father had migrated to Canada to work as a gold miner but eventually became a merchant.

Gin said even though Kamloops had a strong Chinese community back then, there was deep, widespread discrimination.

"They weren't allowed to own property on one side of the river. They weren't even allowed to bury their dead in the city cemetery," said Gin.

Even their children — born in Canada — were not allowed to vote.

Despite that, Lee, who had been working as a farmer, signed up for the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1916 and joined the 172nd Battalion. He trained as a machine gunner within the unit before heading to France.

Honouring Lee at home

His name is carved into the stone cenotaph in Kamloops alongside other local soldiers who were killed in the First World War. But many didn't realize he was part of the city's Chinese community until only recently because Lee can also be an English name.

"We should be so proud of him," said Elsie Cheung, president of the Kamloops Chinese Freemasons.

Another fundraising effort is underway to build a gazebo at the city's Chinese cemetery.

It would be perched at the top of a small hill, looking over more than 200 graves, many which are marked with simple wood stakes.

"It's amazing," she said.

"He counted himself as a Canadian, even if he wasn't recognized as a Canadian."

After learning about his story a few months ago, she has spent hours looking into Lee's family history.

Cheung discovered that Lee's father died and his mother and most of his siblings returned to China even before Lee enlisted.

She found that Lee has an 85-year-old nephew still living in Kamloops, and her goal now is to try and track down his family living in China.

"I would love to reach out to them and tell them about his story in Canada."