'The system failed': addict kept getting prescribed opioids, says grieving mom

A Steinbach mother says her daughter is dead because the health-care system helped fuel her drug addiction.

All Carol Ward has left of Lisa Erickson, 32, is an urn of ashes and the kit bag of drug paraphernalia and prescription bottles she found with her daughter when she overdosed on opioids, including possibly carfentanil.

"Carfentanil was her drug of choice," said Ward.

Ward found her daughter, her wrists racked with track marks and without a pulse, on April 4.

"To find her the way I did was just so heartbreaking. It was my worst nightmare ... that I'd been living for two years," she said through tears.

"When I got there she was sitting on the bed with her back up against the wall with everything on her lap. Pill bottles, powder, syringes. And she wasn't moving," she said.

Ward called 911 while another woman at the house started CPR and injected a dose of Narcan into Erickson's thigh. Narcan, or naloxone, can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

Paramedics arrived and gave Erickson several more doses of Narcan. After about 40 minutes, Ward said they detected a weak pulse, so they transported her to Seven Oaks Hospital where she was put on life support. But doctors told Ward the swelling in her daughter's brain was too severe and there was no detectable brain activity.

At a minute to midnight, she was taken off of life support.

'A perfectly healthy 32-year-old who was an addict'

Erickson didn't sink into drug addiction until after she was prescribed painkillers.

She grew up in Telegraph Cove, B.C., where her father was a commercial fisherman. She had many friends, loved the outdoors and taught herself how to play the guitar and keyboard.

"She was always happy, always good with her friends ... she grew up to be such a compassionate child and person," said Ward.

When Ward's father fell ill, she took her three daughters to Winnipeg. The move was "toxic" for Erickson, her mother said.

Soon after, Erickson got pregnant at 17. During her pregnancy she developed ulcerative colitis, which required long hospital stays and prolonged bouts of morphine treatment. Ward says her daughter recovered from the colitis — which had only flared up during pregnancy — but not from the morphine addiction.

In the years that followed, she went on the provincial methadone program several times, but it didn't work for her.

In 2014, she found a doctor who would prescribe her between 30-90 mg of morphine tablets to be taken between two and five times a day, in quantities ranging from 40 to 120 pills.

"She would go to the doctor and say, 'I have colitis really bad, I'm having a lot of pain, I'm in a flare-up,' and she'd get opiates prescribed," said Ward.

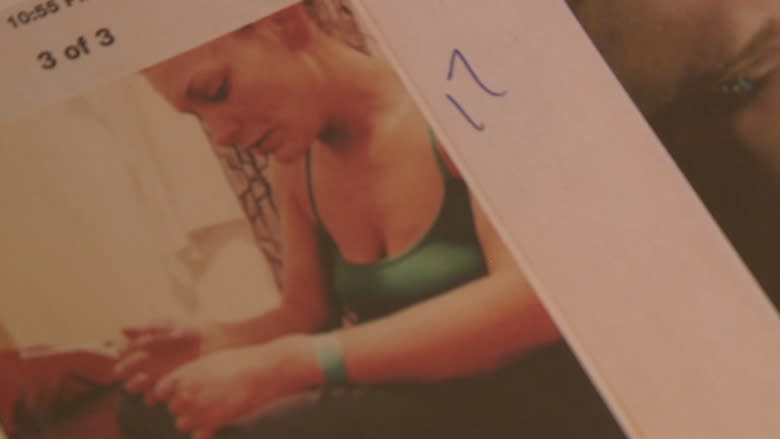

Ward said she confronted that doctor with photos of Erickson shooting up the crushed morphine in 2014.

"Why are you giving opioids to a drug addict?" she recalls asking him.

"Oh she's in so much pain, I hate to see my patients in pain," she said he replied. But she said he assured her he'd wean her daughter off of the medications.

When Ward discovered Erickson's body, she had two bottles of morphine prescribed by the same doctor with her.

"Doctors are supposed to save our children, not kill them. And that's what I see. He helped kill my daughter. He did. He helped kill her."

Ward said she was told the autopsy didn't reveal any need for painkillers.

"She didn't even have a sign of ulcerative colitis. There was no scar tissue, no ulcers, nothing. Perfectly healthy colon."

Now, Ward's waiting on the results of the toxicology report, which will show the cocktail of drugs in Erickson's system when she died. It will also include records of all medications prescribed by that doctor. She plans to file a complaint to the the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba based on the results of that report.

"There needs to be something done about all the doctors out there who are prescribing opiates for mental pain," she said.

"She was a perfectly healthy 32-year-old who was an addict."

Second carfentanil overdose in a week

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba does not have a disciplinary file opened on the doctor.

One Winnipeg pharmacist says though it's rare, some doctors become known for prescribing opioids to addicts.

"They're empathetic to what's going on and they have a tough time saying no. When you honestly care about that person, whether it's a client or your child, how do you say no?" Greg Harochaw, pharmacist and manager of Tache Pharmacy.

He said given the high dose of morphine Erickson was on, it was likely she had developed a resistance to the morphine and had turned to carfentanil to get the high she was seeking.

"Tiny amounts of carfentanil can give you the same effect as much larger amounts of fentanyl or heroin or morphine," said Dr. Alecs Chochinov, medical director of the WRHA emergency program.

"A tiny amount can be lethal."

More and more, he said, carfentanil is being added to other drugs that are advertised on the street as fentanyl or heroin.

As cases of opioid overdoses continue to flood emergency departments across Canada, Chochinov says hospitals in Winnipeg are struggling to find the resources to deal with them. Especially when it comes to patients that have overdosed on carfentanil, which is 100 times more potent than fentanyl and 10,000 times stronger than heroin.

"The amounts of naloxone that are required to treat it are enormous, much higher than with morphine or heroin or other historical opioids," he said.

Three days prior to her fatal overdose that landed her at Seven Oaks Hospital, Lisa Erickson was treated with naloxone for a carfentanil overdose.

She walked out of the hospital after the drug was out of her system, a fact her mother learned after her daughter's death.

"They may as well have just put the carfentanil in her hand and the Narcan kit and and say, 'Here, go again," she said.

"Because for someone to go into the hospital twice within the same week for an overdose? That's someone who's a danger to themselves."

'Another system failure'

In February, Erickson and her boyfriend were arrested together in a Winnipeg hotel. They were charged with possession of drugs for the purpose of trafficking and possession of a weapon. Police found two stun guns disguised as flashlights, though according to Ward, Erickson claimed she did not know about them.

Erickson's boyfriend was taken into custody where he remains in a detox program at Headingley.

Erickson was released on a promise to appear.

One of her sisters and her mother visited her in a hotel room in February to buy her lunch, suspecting she hadn't eaten in several days.

"She was loaded up like a homeless person living in her car ... she was freaking out because she had no money ... She was trying to find her next fix."

When Ward refused to help her get drugs, she said her daughter "freaked out," which prompted her other daughter to phone for an ambulance, concerned she may have overdosed. Instead, Ward said the police showed up.

"They took my meth," she remembers Erickson telling her angrily, after the officers left.

"If they had arrested her for being in breach of her conditions, she'd be alive today. So, another system failure," said Ward.

'Long before it was too late'

She said she's grateful for the ICU nurses and hospital staff at Seven Oaks Hospital who cared for her daughter in her final hours.

"They were compassionate and so gentle and caring with her," she said.

But she wonders how all the medical professionals Erickson came into contact with couldn't do anything to help her.

"That should've been there [for her] long before it was too late," she said.

Ward said Erickson had always hoped to go to the Aurora Recovery Centre, but Ward couldn't afford it. She always dreamed of getting clean and returning to the B.C. coast.

"People that are like her, they can't wait six months to be in rehab," she said.

Erickson's daughter, now 13, loves to sing, spend time with family and draw, like her mother did. Ward said the teen knows she died of a drug overdose and understands why she'll continue to be raised by her grandmother.

"My daughter was an addict. And for years I blamed her. I can't blame an addict for being the way they are. It's the system that's failed. And it's gotta be corrected," she said.