'Where kids can come express themselves': Yukon's Shakat Journal rises again

It's not often that long-dormant publications come to life again, especially today as print media everywhere is under siege.

But that's exactly what happened in Whitehorse this week. The Shakat Journal is back in print, 26 years after it folded.

The journal was originally launched in 1980 by Ye Sa Ta Communications, the Indigenous society that also published the now-defunct Yukon Indian News. The original Shakat was published in the summer months and was aimed at tourists. It was prepared by First Nations youth.

That came to an end in 1991, when federal funding cuts forced it out of print.

The new Shakat is also put together by youth and aimed at a younger audience.

26-year-old editor-in-chief Paige Hopkins says young people need to hone their skills and be involved in society.

"If we have nothing to work towards, we're not going to do anything, we're just going to sit around and drink and do drugs and fall into those habits that are not going to benefit us, or benefit our communities," she said.

"Having a place where kids can come express themselves and build those skills is paramount to our future. Giving kids skills that they can use on their own is huge."

Hopkins says young people are desperate for creative outlets that not only encourage their opinions, but also treat them with dignity.

Kwanlin Dün First Nation chief Doris Bill agrees.

She remembers working on the original Shakat Journal as a youth. Today, she leads her First Nation with a strong emphasis on protecting vulnerable youth.

"The top concerns I hear from young people today ... is their need for self-expression, their want for inclusion. And their desire to be heard," Bill told a crowd of people gathered for the official Shakat re-launch this week.

"I am a strong advocate for music and the arts. I believe wholeheartedly in its abilities to break down barriers, and more specifically, in the healing powers it provides."

'I am contributing, I am getting word out there'

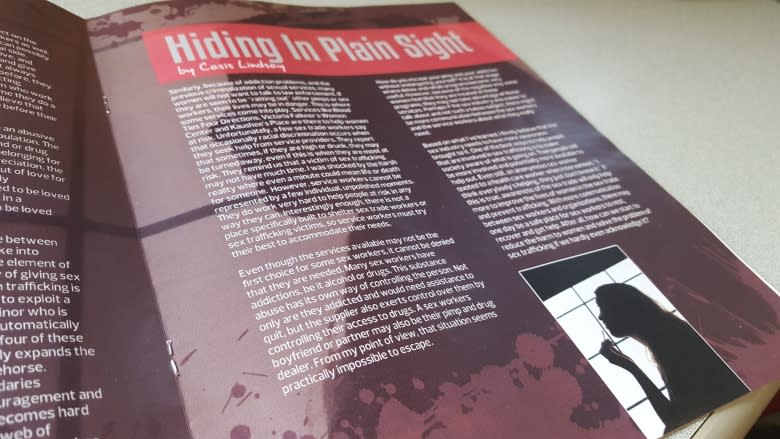

The first new issue offers light-hearted fare — a feature on Star Wars versus Star Trek — but it also doesn't shy away from grittier topics, such as 16-year-old Casis Lindsay's exploration of the sex trafficking trade in Whitehorse.

"It was a tough article to write. It's serious," Lindsay said.

"And the biggest struggle was: I was there to protect the women. I couldn't let any details slip that would identify anyone ... I learnt a lot while I was doing it.

"Writing these articles gave me such a good feeling, I am contributing, I am getting word out there."

Lindsay was inspired by her first foray into journalism. She discovered that journalism has the power to shine a light into dark places.

Hopkins says that's a big part of Shakat's mission.

"Whatever issues we find important, and that are bothering us, and we think we need to change, we're going to follow," she said.

"And we want to hear from everyone. We're going to pursue that, whether it's fun and lighthearted or whether it's tough and gritty and makes people feel uncomfortable, 'cause that's life. That's journalism."

The journal is produced both online and as a printed magazine. The e-version will be updated quarterly, and the print edition will come out twice a year.

The launch event was celebrated with an original song, "Millennial Anthem", written and performed by Jeremy Linville.

A vehicle for reconciliation

Gord Loverin is a Tahltan and Tlingit journalist who worked on the original Shakat in the 1980s, and served as both coordinator and mentor for the new version.

He says the journal is a powerful vehicle for reconciliation, adding that Shakat welcomes all youth, regardless of race or gender.

"They wanted to be able to tell stories that crossed cultural barriers, not that only looked at Aboriginal culture and heritage. They wanted to explore those options, so that non-Aboriginal millennials could understand their neighbours," Loverin said.

"Also, they started looking at each other and they're saying, 'look, we don't look at colour, we don't look at race, we don't look at culture as barriers. We want to celebrate them, and we want to learn about it, and we want to learn about each other.'"

Alexander River Gatensby, chief videographer for the journal, said Shakat is "probably one of the best things that has ever happened to me."

"It's one of the most fun things I'll ever do, it's one of the most cool things I'll ever do. I'm going to be involved for as long as I can be. I can't express how important this is to me, having this creative outlet, being able to express my creative vision. It's amazing."

Uncertain future

The journal already has several advertisers, but its future is far from secure.

Loverin says Shakat will approach both the Yukon and federal governments for financial assistance.

"Unfortunately, we're going hat-in-hand to the territorial and federal government, and we're seeing how they can help — at least in its infant years — support the magazine so that it can get to a level where it can be self-sustaining."

Despite the financial uncertainty, Hopkins has ambitious plans. She wants to reach rural youth, who can sometimes feel isolated. She doesn't want Shakat to be solely focused on Whitehorse.

One idea, she says, is to organize Shakat clubs in schools.

"They would be able to write their stories, and send them to us. And we could all network, and connect and work together, because we might be isolated by distance," Hopkins said.

"We have internet, we can talk instantly, or we can send stuff to each other — it doesn't take a few hours to drive. If we're all connected, we can all work together. This way they won't feel so isolated ... And we'll all feel a little closer."

Hopkins has a message for all Yukon youth.

"I want to hear them ... I want to pass on their messages. I'm here for them."