Astronomers find more clues behind 'Great Dimming' of giant star

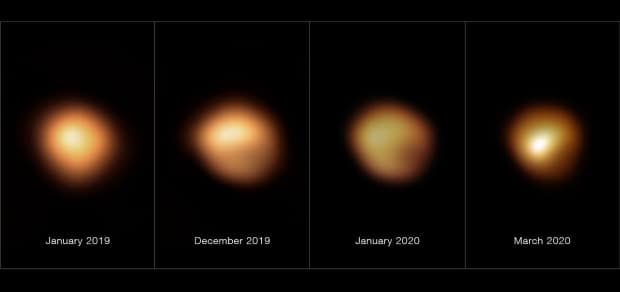

Between November 2019 and March 2020, a massive star dimmed in a way never seen before, puzzling astronomers. Some people hoped that it was an indication that the star was dying and that it would result in a spectacular explosion that would have illuminated the sky like a full moon.

That never happened, and the star — Betelgeuse — returned to its regular brightness. Now in a new study, astronomers believe they may have figured out why this happened.

Betelgeuse is a red supergiant, a massive star found in the constellation of Orion that lies 700 light-years from Earth and is believed to be roughly 1,400 times larger than our sun and 14,000 times more luminous.

The star is also a semi-regular variable, meaning that its brightness waxes and wanes in cycles. Eventually, red supergiants run out of fuel and die in a spectacular explosion, a supernova. Some who were watching the dimming wondered if this was a sign of its impending death.

But in 2020, it became apparent that its dimming was not part of any of its regular cycles, but exactly what was causing it remained a mystery.

Now, a new paper published in the journal Nature on Wednesday suggests that the dimming was caused by dust that obscured part of the star.

How that dust got there is actually linked to something else entirely, however: a period of cooling on the star.

The authors of the study believe that gas was released by the star, something that is believed to be somewhat of a regular occurrence. But then part of Betelgeuse cooled, which caused the gas to turn to dust that then obscured part of the star.

Miguel Montarges, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, Université, has been studying Betelgeuse his entire career. Just 12 months before the "Great Dimming event," he was ringing in 2019 at the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) collecting data from the giant star.

"I remember wishing that something would happen this year because I was at the VLT observing Betelgeuse," he said. "Every year, I make the wish for a big comet or a supernova. And I said, 'I want something to happen.' And something happened."

All eyes on Betelgeuse

When the dimming began to be observed by astronomers, Montarges was skeptical.

"In November, when we first received the email saying, 'Oh, it's a bit fainter than usual,' my reaction was, it's a bit too early to say that something significant is happening," he said.

But soon, there was no ignoring it. So Montarges thought he'd take some observational data and prove that nothing out of the ordinary was happening. He figured it was two cycles of Betelgeuse's normal dimming that happened to come together to form a deeper dimming.

How wrong he was. The star eventually dimmed by roughly 25 per cent.

The event was observed by astronomers around the world using instruments that viewed it in all sorts of different ways.

WATCH | The dimming of Betelgeuse:

"We had small telescopes, big telescopes, space telescopes; we had telescopes in the radio [spectrum], in the infrared, in the ultraviolet," said Emily Levesque, a professor in the department of astronomy at the University of Washington who published an accompanying piece in Nature on the findings.

"We were looking at polarized light, we were looking at spectra. I loved it as a demonstration of how many different tools we can take advantage of and astronomy to really go from 'Hey, that was weird,' to now we can explain what's happening."

'Snapshot of this star'

Stella Kafka, director of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, who was not involved in the study, said that one of the amazing things is how so many instruments to collect data on Betelgeuse.

"We're looking at the snapshot of this star. But the same time this snapshot is clarifying some things for us for that particular evolutionary stage," she said. "So in principle, the nice thing about this particular manuscript is that they're introducing new data, new techniques."

Studies were released by several astronomers, with some suggesting that the dimming was due to cooling; others that it was a cloud of dust that had hidden part of the star from us. The new study suggests it was a combination of the two.

In the study, astronomers came up with four scenarios that could account for Betelgeuse's dimming:

A "potentially local" decrease in temperature that made it fainter.

A newly formed cloud of dust that blocked it.

An occultation (where something passes in front of something else) of dust that happened to be passing in front of it.

A change in angular diameter (the diameter of Betelgeuse as seen from Earth)

The authors ruled out scenario three since a cloud of dust that was passing by would have moved across different parts of the star, which wasn't observed. Scenario four was also ruled out after looking at data collected from two instruments on the VLT.

Instead, they believe that some time before the Great Dimming, the star released a bubble of gas. Initially, the region around the star remained too warm to allow dust to form. However, some time along the way in its normal cycle, the star cooled just enough to allow that to happen.

Betelgeuse isn't the only red supergiant, although it's probably the most well-known and studied, and it's not known whether this type of event is typical for these giant stars. Antares is another well-known red supergiant, found in the summer constellation (in the northern hemisphere) Scorpius.

A study on Antares lead by Emly Cannon, co-author of this recent study and an astrophysics PhD candidate at KU Leuven in Belgium, found that there is a dust clump around the star, although it's not in our line of sight.

"So that goes some way in showing that maybe these dust clumps … might not be that special," Cannon said. "Maybe that's what we're seeing for all red supergiants. It's just this one happened to be ejected right towards us where other times it's just being ejected from parts of the star we're not seeing."

While Betelgeuse will explode some day, it's unlikely that this event was any indication that its death is on the horizon. It's likely it will take tens of thousands of years or even hundreds of thousands.

Montarges will continue to keep an eye on Betelgeuse to help better understand stellar evolution and our place in it.

"It's amazing that we are a tiny part of the universe, trying to understand the universe."