An Attempted Coup Tried to Stop Japan’s Surrender in World War II. Here’s How It Failed

The Japanese refer to the attempted coup d’état on Aug. 14, 1945, the last night of the Second World War, as the “Kyujo Incident.” Ringleaders Kenji Hatanaka and Jiro Shiizaki, officers at the army ministry, led a battalion of rebels into the Imperial Palace. Lying brazenly, Hatanaka and Shiizaki told the commander of the Second Imperial Guard Regiment that the top brass had ordered the palace sealed off from the outside. The guards, believing that a broader revolt was afoot, agreed to comply with their instructions pending the arrival of the Eastern Army. But Lieutenant General Takeshi Mori, commander of the guards, smelled a rat. Refusing to join the plot, he was shot dead in cold blood. The confederates then forged an order in General Mori’s name and sealed it with Mori’s official stamp. The document instructed the Imperial Guards to occupy the palace, seal off communications with anyone outside the moats and “protect” the emperor against unspecified threats.

In the palace itself, the imperial stenographer was putting the finishing brushstrokes on the Imperial Rescript on Surrender. The emperor’s seal was fixed to the document, making it official. Shortly before midnight, Hirohito entered a soundproof bunker under the palace, where a team of NHK technicians had set up recording equipment. The emperor read the surrender rescript into a microphone. The recording was four minutes and 45 seconds long; the English translation, broadcast overseas the same day, totaled just 652 words. Only one take was needed. The technicians transferred the recording onto two vinyl records, which were pressed on the spot and deposited in a safe under the palace.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

With the Imperial Guards behind them, the coup leaders occupied the palace and cut the phone lines. Persuaded that the Eastern Army was on its way, the guards closed the gates and cut off all automobile and foot traffic into and out of the walled compound. The rebels searched the catacombs under the palace, arresting and interrogating staff members at the points of bayonets. They searched for Marquis Kido, the lord privy seal, but could not find him. They also failed to find the phonograph recordings. With an air raid blackout in progress, the lights were doused and the searchers had to use flashlights. The search parties did not know the layout of the underground labyrinth of passageways and bunkers, and found it difficult to interpret the archaic signs marking the locations of various rooms.

Meanwhile, other co-conspirators spread out through Tokyo and Yokohama. The aged Prime Minister Suzuki, who had survived an assassination attempt nine years earlier, was warned moments before his would-be killers arrived. Other detachments occupied the major radio stations, intending to intercept the emperor’s surrender recording before it could be broadcast to the nation.

As dawn approached, Hatanaka and Shiizaki realized that their options were limited. No general or admiral had committed to support the revolt. Even Admiral Onishi, who had been the most passionate advocate of fighting to the end, had given up the cause and was preparing to take the samurai’s way out. General Shizuichi Tanaka, commander of the Eastern Army, was determined to put the rebellion down. A full division of well-equipped troops surrounded the Imperial compound and sealed off the bridges spanning the moat. The exhausted ringleaders, outgunned and outmaneuvered, knew that their bid had failed. At 8:00 a.m. they gave themselves up. Hatanaka begged to be permitted to broadcast a ten-minute appeal over the radio, but was refused. He and Shiizaki were not arrested, perhaps because it was understood that they would take their own lives. For the next several hours, the two men roamed around Tokyo, distributing leaflets explaining what they had done and why. Shortly before the emperor’s broadcast went on the air, both shot themselves.

At 7:00 p.m. that evening, an NHK radio announcer instructed all Japanese to be near a radio at noon the following day: “At noon tomorrow, August 15, an important broadcast will be made. This will be an unprecedented broadcast and the 100 million subjects must listen honestly and solemnly without fail.” Subsequent bulletins added that the broadcast would include “the Jeweled Sound of His Imperial Highness.” In order to ensure that every citizen could hear it, electrical power would be provided to neighborhoods that would normally be blacked out. In anticipation of the momentous broadcast, all musical programming ceased at 10:00 p.m. on the 14th. It would not resume until after the emperor had been heard.

As the coup attempt was in its last throes, one of the two vinyl phonographs was delivered to NHK, Japan’s national broadcasting corporation. An hour before the scheduled broadcast, the record was in the hands of the broadcast engineers. Troops of the Eastern Army had taken control of the streets around NHK headquarters. Both the coup plotters and the authorities knew that once the emperor’s voice went across the airwaves, there would be no turning back, and no revolt could possibly succeed.

At 11:59 a.m., air raid sirens churned briefly, and then fell silent. The audiences listened with breathless intensity. The streets fell dead silent. In many places, the summer cicadas warbled loudly, and people cocked their heads to hear. At the NHK studios in Tokyo, a technician dropped the needle on the phonograph, and then stood and bowed his head.

A voice came across the airwaves. It was faint, reedy, and tremulous. Many found it difficult to follow amid a hiss of static. It began, “To Our good and loyal subjects.”

undefined

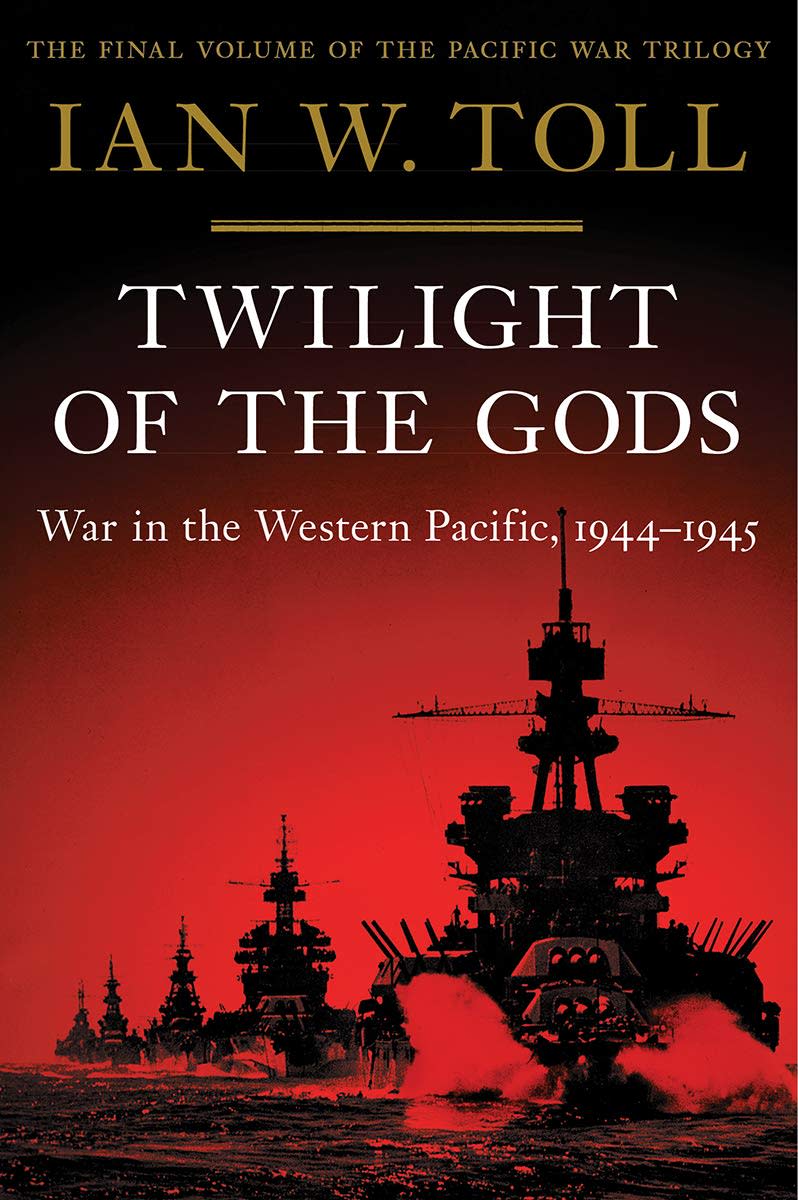

Excerpted from Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945 by Ian W. Toll, available soon from W. W. Norton & Company.