Avi Arad: From ‘Blade’ To ‘Morbius,’ Three Decades Of Mining Marvel

In Hollywood circles, Avi Arad was Marvel when Marvel wasn’t cool. Today, Marvel represents Hollywood’s gold standard for source material but that was hardly the case back in 1992 when Arad’s long odyssey with the brand got underway with Saturday morning cartoons like X-Men and Iron Man, the latter starring Robert Hays (aka Ted Striker of Airplane! fame) as the voice of Tony Stark.

“Yes, it’s come a long, long, long way,” Arad said of Marvel’s stature and brand mystique these days. In 2018, Marvel characters were featured in top film hits from three different studios: Fox’s No. 1 box-office performer was Deadpool 2; Disney’s two top-grossing releases were Avengers:Infinity War and Black Panther; and Sony’s No. 2 and No. 5 top-grossing hits for the year were Venom and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. The amazing reign of Marvel IP and the unprecedented success of Marvel Studios (21 films since 2008 with $18 billion in box-office receipts) are bittersweet topics for Arad, however.

Related stories

'Captain Marvel' Soaring To $800M+ Worldwide Today

'Danger Girl': Jeff Wadlow Set To Direct All-Female Spy Tale For Constantin Film

'Dial H For Hero' Preview: Reconnecting The Party Line Of The DC Universe

Stan Lee and Avi Arad, 2002.

The 70-year-old producer was once was at the center of the Marvel Universe but he gave that up in 2006 when he resigned as Chairman and CEO of Marvel Studios even as the Hollywood newcomer was ramping up Iron Man, the 2008 live-action feature film starring Robert Downey Jr.

Arad, whose voice still has traces of his native Tel Aviv, declined to delve into the reasons for his resignation but he did say he grew frustrated with the changing culture and crowded corridors of the upstart Marvel Studios.

“I’ll tell you now, it was only my choice [to leave] because one day came when I said, ‘I think I’ve had enough of this,'” Arad said. “The company was growing with the CEO of this, and the CFO of that, but it was basically [a situation in which] we were doing everything but now there’s way too many people for me to deal with. And everybody wanted to make movies. Everyone. I mean, you name it, the people who were cleaning the place wanted to read the scripts.”

It was a far cry from Arad’s style during the 1990s when the stakes were often smaller but he mostly enjoyed autonomy and thrived as a maverick persona that was as colorful as the characters he pitched to Hollywood studios. Arad had been a designer in the toy business (with Baby Wanna Talk, My Pretty Ballerina, and Magic Bottle Baby among his credits) and was working with Isaac “Ike” Perlmutter at Toy Biz in when Marvel and Toy Biz struck a business pact and the companies became increasingly intertwined. Arad had shown an affinity for the characters (the X-Men toy line he designed for Toy Biz had racked up $30 million in sales) and was dispatched to Hollywood to see if he could turn his action figures into screen heroes, too.

Hugh Jackman and Avi Arad, 2003.

The bankruptcy filing by Marvel Comics in 1996 could have been the end of those Hollywood dreams but in the end it effectively cleared the way for the savvy Perlmutter and Toy Biz to seize control of the entire Marvel brand in 1998. Arad now had the Marvel Universe as his toy box — the same universe of heroes, villains, gods, monsters, aliens, spies, and androids that had fascinated him as a youth reading Spider-Man and Iron Man comics translated into Hebrew. (“In the comics I read Iron Man was called Man of Steel but it sounds the same in Hebrew,” Arad noted.) He had loved the characters as toys and then as television cartoons and he was impassioned to see them on the silver screen.

The only problem: Hollywood wasn’t all that interested.

“Look, X-Men will always be my first love and, as you know, I did the [animated] show from ’93 to ’97 because I related to being a mutant,” Arad said without irony. “I really did. It was wonderful when the show did well and the best thing about it was that kids all over the world were waiting for this kind of prophecy and the toy company went crazy because everybody was collecting action figures and to me, it was, as a sign of what to do. Movies. It was really clear, you know, that if we have the right idea and we execute it right, it can’t miss. I learned from the toys and just have to convince the world that thing is entertaining, fun, thoughtful.”

I first met Arad in the first half of 2001 on the set of Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man film. I was writing for the Calendar section of The Los Angeles Times and it was my first visit to a working Hollywood set. The two of us sat down in a pizzeria in downtown Los Angeles after watching Tobey Maguire film an alleyway scene where he realizes that the still-sore spider-bite on his hand has changed him forever.

I remember Arad was proudly wearing a shiny, silver Punisher skull ring, a Spider-Man ball cap and a Wolverine shirt under his jacket that morning, but my strongest recollection was his gusto for all things Marvel. I reminded Arad of our long-ago meeting to Arad and he chuckled at the memory. He also hinted that the passion I perceived that day was corked-up frustration in disguise.

“Well, as you know, better than most, I was basically climbing a rock straight up back then,” Arad said early this week. “It was me almost getting to the top and [then it would] roll right back down because the industry did not consider comic books to be source material. You know, it was a rough ride and you had to believe in it to try and convince people. Studios actually were the hardest to convince. You and I understand the power of this stuff because we loved it first as readers. It was hard to get studios to ever look at a comic book and even when they did they couldn’t see it.”

However, Arad said, the winds of change were in the air.

“The good news was that it was a time where the kids who just went to art school, or went to writing school, or went to filmmaking school, and so on, they were the ones who actually loved the comic book culture, and many of them were just beginning,” Arad said. “That kept me going.”

Raimi was one of those still-ramping talents in Hollywood back then who knew the power of Marvel Comics mythology. Raimi told me that day back in 2001 that his mother had painted a Spidey mural above his childhood bed as a birthday gift, so he literally fell asleep at night thinking of the wall-crawling hero. That, more than anything, is why Raimi was the perfect choice to bring Marvel to the big-screen in a powerful way.

(And if Raimi happens to be reading Deadline today, a message from Arad: “I would love to see what kind of animated Spider-Man movie we’d get from Sam Raimi so if he sees this, ‘Call me Sam!'”)

Another Marvel true believer was Michael De Luca, the president of production at New Line Cinema, who agreed that a relatively minor 1970s character from Marvel’s Tomb of Dracula comic series was worthy of a feature film. The result was Blade, the 1998 action-horror film that gave Arad and Marvel a foothold success.

Avi Arad and Tobey Maguire, 2002

“He was a super geek and he understood the story and the fact that there was no comic book actually saying Blade on it didn’t bother him at all,” Arad said. “It was unheard of then. But we were right and, as we say, the rest is history.”

Things didn’t change overnight but Blade, Spider-Man and Bryan Singer’s two X-Men films at Fox (in 2000 and 2003) began to erode the entrenched Hollywood view that Marvel characters were too esoteric, weird, or unheroic to connect with mainstream moviegoers — an opinion that had been locked-in by the complete failure of Lucasfilm’s Howard the Duck in 1986.

An essential aspect of the rising fortunes of Marvel properties was a technological one: CG visual effects had reached a level that made it finally (and fiscally) possible to reasonably match the fantastical visuals of Marvel Comics artists like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, John Buscema, John Romita, and John Byrne, to name just a few.

Avi Arad and Kevin Feige, 2010.

The Columbia Pictures Spider-Man films would become nothing less than Sony’s all-time biggest franchise. But there were plenty of non-starters, too: Black Panther was going to be a Fox film, Iron Man was set up at Sony, a Doctor Strange project came and went, as did a dozen other Marvel projects.

There were some other Marvel projects, like filmmaker Ang Lee’s Hulk, for instance, that Arad loved (and still loves) far more than the public. And then there were Marvel movies that were bloated, off-key, or convoluted, like Brett Ratner’s X-Men: Last Stand (2006) or Raimi’s Spider-Man 3 (2007). Those movies were Arad’s freshest legacy when he left Marvel Studios in 2006 and they don’t hold up well now, especially in comparison to Iron Man and the Avengers films that followed Arad’s defection.

In the decade after Arad’s departure, Kevin Fiege, a former protege of both Arad and X–Men producer Lauren Shuler-Donner, became the chief architect of Marvel Cinematic Universe and its unprecedented latticework of interconnected franchises that makes the brand far bigger than any of its individual characters or its many stars.

Arad, meanwhile, started his own company, Arad Prductions, and continued to develop Marvel-based projects, most recent among them for Sony with the 2018 hits Venom and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. He speaks philosophically about his Marvel Studios days now.

“The time came when, for me, it was time to move on,” Arad says now. “There are a lot of theories behind it, but it really doesn’t matter. I tried correcting some of them and it always looked like an aggressive posture by someone who is begrudging.”

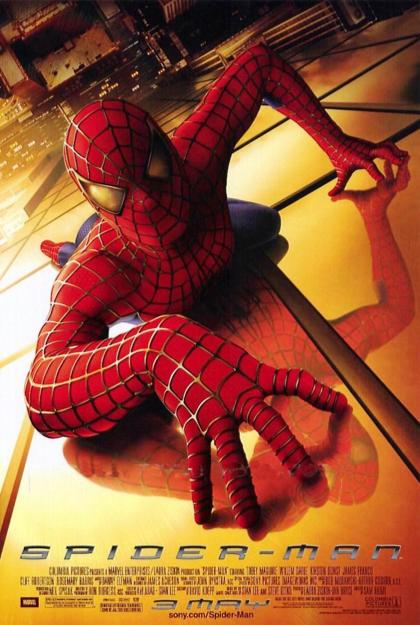

Sony Pictures.

(Arad was most likely referring to an open letter to Hollywood he penned in 2014 in which he popped off about media coverage of Marvel Studios that showered praise on Feige’s achievements but omitted or dismissed Arad’s ramp-up contributions. “It will sound arrogant to you, but I single-handedly put together the Marvel slate,” Arad huffed in the 2014 letter. “Read it carefully and you will notice the natural progression of the character’s design to get to where we are today.” Arad used the letter to point out that he had secured the go-ahead financing for the Marvel slate and that he had “forgiven” Feige for “following orders and taking the credit.”)

A year after Iron Man hit theaters, Hollywood was shocked by Disney’s stealthily negotiated $4 billion acquisition of Marvel Entertainment, the parent of the upstart Marvel Studios. In hindsight, Arad has little to say about the deal other than noting that the price was probably way too low.

“It was a brilliant move and, in all fairness, Disney bought us inexpensively if you look at what’s happening today,” Arad said, a nod to Disney’s latest empire expansion with the Fox mega-deal. “But as I said, for me, when it became time to go, I went. But I knew there would be life after that…”

True, life did continue and so did Arad’s Hollywood adventure. With his Arad Productions, he entered a different career phase but his focus remained the same. As producer of Sony’s Amazing Spider-Man (2012) and Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014), Arad remained a Marvel specialist — he might have left the Marvel payroll but he was still in the Marvel Universe of IP.

Sony Pictures.

Late last month, Arad’s odyssey with Marvel properties took him to an unlikely destination — the stage of 91st Academy Awards, a gleaming setting that would have looked like Asgard to the eyes of young Arad in his schoolboy days in the Ramat Gan district of Tel Aviv near the southern banks of Israel’s Yarkon River.

It was the Spider-Man Into the Spider-Verse success that brought Arad to the Oscars and when the Sony film claimed this year’s Academy Award for best animated feature film it provided a moment of redemption and validation for the man who carried the Marvel banner in its leaner Hollywood years.

The movie has been hailed by critics and scored an unexpected commercial success ($368 million worldwide gross off of a $90 million production budget) that came on the heels of Sony’s equally unexpected Venom success ($855 million global, $100 million budget), which up-cycled the grotesque Spider-Man villain into a stand-alone box-office hero (and a hero invulnerable to bad reviews, at that).

Together, the one-two punch of unlikely Spider-related hits (and their inevitable sequels and spinoffs that will soon take shape) makes Sony’s deal with Marvel Studios to share Peter Parker as an Avenger look like the best rope-a-dope maneuver since Muhammad Ali’s boxing days.

It was an especially brisk Oscars broadcast this year and Arad was denied the global Kodak Moment he wanted (he got cut off at the microphone before he could pay tribute to Marvel icons Lee and Ditko, effectively squelching the only onstage mention of Spider-Man’s co-creators, both of whom died in 2018.

.

Arad said there was another missed chance on awards night — Arad said he was rooting hard for Disney’s Marvel Studios, Feige and Black Panther to pull-off their long-shot bid in the Best Picture race. The hit film was the top-grossing domestic release of 2018 and its nomination made it the first comic-book superhero movie to earn that kind of respect from Academy voters. But Arad hoped for more.

“I was heartbroken that Black Panther didn’t get the Academy,” Aaad said. “It could have, but you know, [the voters] they always looked at superheroes like it was a ‘Yabba dabba doo’ kind of a thing versus something that mattered or something that was going to last.”

Arad himself still matters and he’s proven himself to be a lasting institution in a business that goes through producers faster than, well, Spider-Man actors. With the passing of Lee, Arad is now the elder statesman of sorts for Marvel’s efforts in Hollywood. And Arad is worthy of that title, too, according to Sony Motion Pictures Group chairman Tom Rothman, who also worked with Arad in the X-days of Marvel’s Tinseltown turnaround.

.

“Avi and I first met back in days of yore, when we wrestled the very first X-Men on to the screen,” Rothman said Friday. “No big Marvel movie had been made at that time, and many folks thought we were nuts, but Avi never wavered then, and never has in all the years and many giant films he has made since. From X-Men to Venom to Spider-Verse, he has been and remains a master producer and a true gentleman. I love him.”

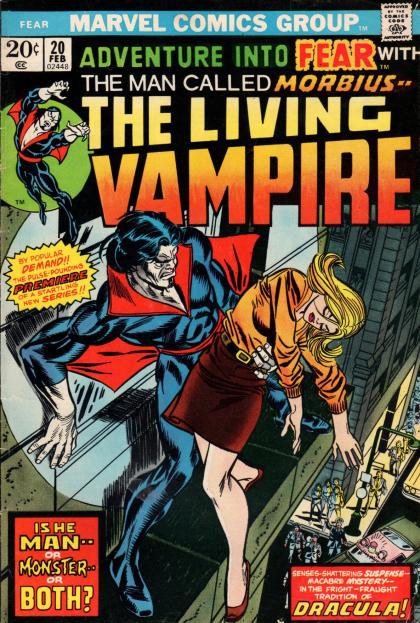

The past and present are less interesting to Arad than the future — although history has a tendency to repeat itself in some ways. He is busy now, for instance, ramping up Morbius, the Sony film that will star Jared Leto as Dr. Michael Morbius, the “living vampire” introduced in October 1970 in the pages of Amazing Spider-Man. The character is a horror-based property with no live-action screen history and zero name recognition with mainstream audiences — which makes him a lot like Blade in the 1990s.

“Wait until you see the way he looks, what we have done with this character, you will love it,” Arad said. “There are so many other great characters on the way, too. You will see. We’re just getting started.”

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.