B.C. rabies death revives interest — and fear — in age-old disease

The ancient Babylonians, Assyrians and Greeks were wary of its telltale symptoms. It claimed the life of one of Canada's governor generals. The disease is a "scourge as old as human civilization" write Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy, authors of Rabid: A Cultural History of the World's Most Diabolical Virus.

So when a Parksville, B.C., man died from rabies on July 13, there was overwhelming interest surrounding his shocking death, triggering a deeper, primordial fear of the virus.

According to a 1988 paper in the Canadian Journal of Veterinary Medicine on the history of rabies in Canada by Richard Rosatte, incidents were first reported in the colonial history of the country during the late 1700s in Quebec.

Rabies claimed Charles Lennox, governor general of Canada, who died after being bit by a rabid fox during a tour of Upper and Lower Canada in 1819.

Wasik and Murphy describe his agonizing ordeal: unable to drink, terrified by the sound of water and ravaged by fever. Victims at this time faced certain death.

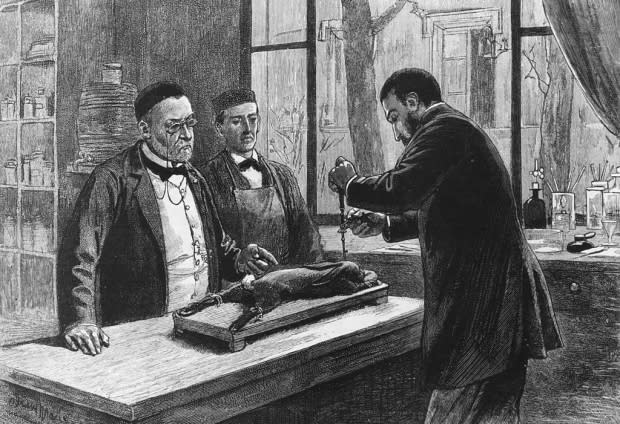

A major shift came when French microbiologist Louis Pasteur and his colleague Emile Roux produced the first rabies vaccine in 1885.

As the majority of cases prior to 1945 involved domestic dogs, the introduction of effective vaccination of domestic animals during the first half of the century in Canada led to a dramatic decline in human cases. Today, the majority of human deaths related to rabies are attributed to areas of the world without widespread, systematic vaccination programs.

Modern-day incidents

In the U.S. and Canada, modern outbreaks of the disease have largely taken place within wildlife populations of foxes, skunks, raccoons and bats. Human deaths are uncommon.

In fact, Bonnie Henry, B.C.'s provincial health officer, has made clear this week's death is "extremely rare."

There have been only two B.C.-originated rabies deaths in the province since 1924; a third rabies death in Vancouver involved an infection originating in Alberta.

All three involved an interaction with a bat.

In 1985, 25-year-old climber and outdoorsman Scott Duncan died after being bitten by a bat that flew into his tent while he was camping north of Edmonton. He later died in Vancouver.

In 2003, an unnamed 52-year-old Lower Mainland man, described in news reports as an avid outdoorsman, also died after encountering a bat.

And this week, health officials said 21-year-old Nick Major contracted the fatal disease after he ran into a bat in an "unusual" daytime encounter during an outdoor trip near Tofino.

These incidents line up with the findings of a 2008 paper on bat-transmitted rabies published in the journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, which said young adult males are more at risk if they practice activities that increase their potential exposure to bats, adding they "may be less inclined to seek medical attention or prophylaxis should a contact, even a bite, occur," because the "cryptic" nature of bat bites can make them easy to miss.

Despite this, the paper found the incidence of bat-transmitted rabies in humans in Canada very limited: there were only six such cases from 1950 to 2008.

Powerful cultural legacy

And yet, the perceived threat of rabies still has a powerful cultural resonance, building upon thousands of years of human history.

As Wasik and Murphy write in Rabid, the way the virus ravages its victims and targets our most trusted family companions — immortalized in films like Disney's Old Yeller and Stephen King's Cujo — contribute to our heightened concern.

"Rabies has receded to become a sort of spectral presence, a ghost story ... [but] we nevertheless cannot wholly free ourselves from the fear," they write.

"It's gone until it isn't."