Teller-turned-robber recalls 1958 bank heist

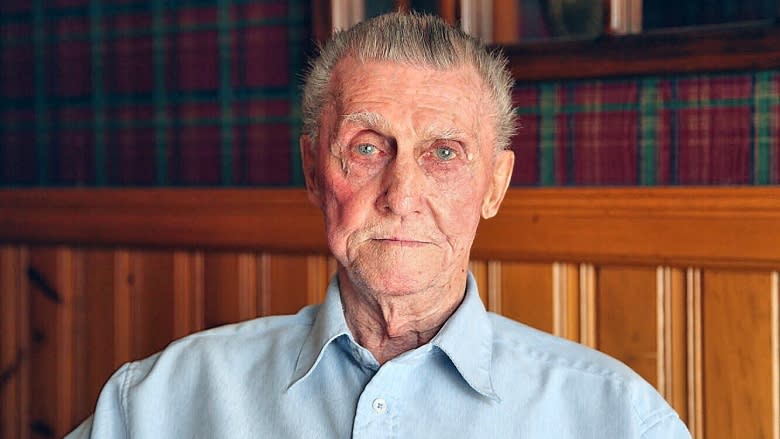

Boyne Johnston sips from a bottle of beer at his favourite Renfrew, Ont., pub, as he prepares to tell the 60-year-old story one more time.

Even at 85, the names, dates and addresses of his flight from justice still come readily to his lips.

"It's embedded in stone, in my brain," he concedes.

"I guess I'd have to start [with] when I joined the bank."

Six decades ago, Johnston was working as a teller at the Imperial Bank of Canada branch on Sparks Street in downtown Ottawa.

One day, he walked off the job with roughly $260,000 — more than two million dollars in today's money — from the vault.

He spent 17 days on the lam and living the high life before being captured in a Colorado night club.

His story recently made headlines when he returned to the former bank, now a swanky restaurant called Riviera, for lunch. Staff shared a photo on Instagram of Johnston wearing a dapper suit and enjoying a glass of champagne.

Johnston had started working at the bank branch when he was 18, but quit when he felt he wasn't being promoted quickly enough.

After a stint working in a mine in northwestern Ontario for his father's drilling company, he returned to Renfrew, where he was rehired by the bank, eventually landing a position working as the head teller at the Sparks Street branch.

Johnston handled all of the branch's monthly ledgers, and was responsible for sending the bank's balance sheets and hundreds of public servants' wage receipts between the Bank of Canada and his bank's head office.

He was good with numbers — but he was also good at drinking and spending money.

Lavish tastes

His favourite clubs were across the Ottawa River in Hull, where he'd spend lavishly, ordering bottles of champagne and enjoying the company of local women. He often had a table in the Rose Room of the long-gone Chaudière Club.

"It was the classiest," Johnston reflected. "Saw Louis Armstrong there. Ella Fitzgerald [too]."

Johnston also bought a British sports car, and dropped about $1,000 on furniture for the Bruyère Street apartment he shared with his new wife — even though the bank had only approved a loan of about $100.

His spending caught up to him in 1957, however, when he ended up unable to pay his rent.

He covered the shortfall with money from the bank, and while he replaced it on payday, the incident opened the young man's eyes to just how easy stealing from his employer could be.

"Only in this branch," Johnston said, "could I have gotten away with what I did."

Mistakes made by other Imperial branches were sent to Johnston's branch as "coupons" to be reconciled, Johnston said.

He would alter the correction notices himself, sometimes by adding a zero to the sum — sometimes by adding more. He then pocketed the difference.

But by the time he'd embezzled $1,000 — the equivalent of $10,000 in 2018 dollars — he knew he wouldn't ever be able to pay it back.

Still, he kept up the scheme, bringing in somewhere around $25,000 and concealing the evidence of his embezzlement by preventing others from handling the coupons.

Then, in September 1958, his bank manager told him he was being promoted to head accountant.

"I'm dead. Next guy moves in [to my job], he's going to find [all the evidence], there's no argument about it," Johnston recalled thinking. "What am I going to do?"

On the run

Johnston said he contemplated escaping to some place like South America, but he couldn't see himself — a kid from small-town eastern Ontario — being on the run forever.

So, he said, he decided he would treat himself to a big, lavish holiday.

One Friday, he emptied the vault reserves into two canvas bags, stashing them in a little-used storage closet while no one was watching.

He then made a big show of having to dash off to Renfrew for the weekend, hastily closing the vault and spinning the lock before the required count of the bank's money could be made.

Johnston returned later that evening, loaded the cash into the trunk of his yellow 1956 Mercury Monarch Phaeton and made arrangements to fly to Los Angeles.

"I had no intention of staying away forever. I'm from Renfrew. I'd just take a holiday, have a good time," he said.

For the next 17 days, Johnston lived the life of a playboy.

He played it hour by hour, never thinking too far ahead. He abandoned his plans to continue from Los Angeles to Hawaii out of fears there might be a customs check — how would he explain a pigskin suitcase bulging with $260,000? — and instead ended up in Twin Falls, Idaho.

There, Johnston began spending the money in earnest, buying a Zenith transoceanic radio for $150 and a sapphire ring. He later purchased a 1959 Corvette and began touring around the western U.S., "seeing the sights."

But the good times didn't last long.

Eventually, Johnston got a call from a good friend and former roommate in Canada who urged him to give himself up.

The friend said everyone back home was worried about him. Johnston gave his friend a word: he'd head south to go deep-sea fishing, but would be back in Ontario by Christmas.

"He said, 'Well, you better get the hell off the phone — because my line's tapped,'" Johnston recalled. "And it was. I'd asked the detectives that picked me up later."

Johnston made his way to Denver, where he checked into a room at the YMCA. He turned on his radio, and the news reported that he'd been spotted in Wyoming — and that there was a $10,000 reward for his capture.

He drank a six-pack of beer in his room and then headed to a local nightclub.

Johnston took a seat at the bar and bought a few bottles of champagne to enjoy with a pair of "bar girls," he said. Two gentlemen pulled up about three stools down.

When he went to the washroom, they followed.

"They cuff me right in the place. We're walking out, the two girls with their champagne [shout] 'Where you going?"

"I say, 'To jail!'"

'I'd do it all over again'

Johnston would end up spending four years in prison in the former Kingston Penitentiary for his crime. His father paid back $20,000 of the illicitly-spent money. His wife, he said, "wasn't too keen on taking me back" — but she did.

After he got out, Johnston turned down offers to write a book about his exploits. Despite his theft, he said he was able to wrangle a job as an accountant.

Johnston vows he's never stolen anything since. He also says he has no regrets about the whole experience — but perhaps not for the reason most people would think.

"I'd do it all over again, but only for one reason," Johnston said.

"Nobody understands until your freedom is taken away what your freedom is. I have such great appreciation for life today."

With files from Trevor Pritchard