Best friends' books teach kids the power of healing, in four languages

Angela Peter-Paul remembers the first time she saw Florence Mazerolle 25 years ago.

"She was so cute, she had this little baby in her belly," she said, her quiet voice warm with affection. "I told her she was going to have a little boy."

It was unusual for her to feel so comfortable with a stranger, she recalls.

"I never used to talk to non-native people, because we were sort of raised to be afraid of them."

Mazerolle remembers a similar feeling of immediate bonding.

"We were simply pulled together," she said. "She's been there since my kids were born, my kids call her Auntie Ange."

That was back in their university days at Mount Allison, where they struck an immediate friendship despite surface differences.

Mazerolle is bubbly and outgoing, Peter-Paul is soft-spoken and reserved. Mazerolle is in banking and finance, Peter-Paul is artistic and attuned to the spirit world. Mazerolle grew up in Peggy's Cove in Nova Scotia and only recently learned she is of Métis heritage, Peter-Paul is Mi'kmaw, born and raised on the Metepenagiag First Nation.

Those differences only deepened their bond over the years.

They also paved the way for a project that is uniquely suited both to their personalities and to the times: a series of self-published picture books that teach the Mi'kmaw and Maliseet languages to New Brunswick's elementary students.

"Angela and I have been talking about projects for years," she said.

Now, with their children grown and gone, they suddenly had time.

Mazerolle, ever the entrepreneurial spirit, gave the creative Peter-Paul a nudge.

"Why don't we write some books?" she said. "Your artwork is brilliant."

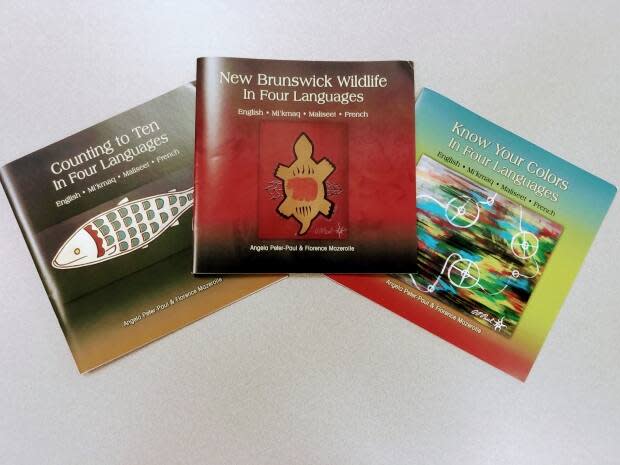

Earlier this year, they applied for and received a provincial grant and started with a series of three books — New Brunswick Wildlife in Four Languages, Count to Ten in Four Languages and Know Your Colours in Four Languages — designed specifically to teach elementary school students to understand other cultures.

"That's how respect comes for other cultures, by understanding their language," Mazerolle said.

Mazerolle crafted the words and drove the entrepreneurial end of the venture, while Peter-Paul provided the history, consulting with her Mi'kmaw and Maliseet elders, and the strikingly beautiful artwork.

Each of the three books are centres around a theme – animals, colours, numbers — and then teach children how to say a word in four languages: English, French, Mi'kmaw and Maliseet, often known now as Wolastoqey, with each word accompanied by one of Peter-Paul's illustrations.

School districts were quick to see the books' educational value.

Two Anglophone districts have bought most of their first edition of the three books, which are now heading into a second edition reprint. They will be available to the francophone school districts as well.

Both Mazerolle and Peter-Paul are thrilled that the books have been so well-received, and are already planning their next series.

Four more books are in the works, including a book about Atlantic Canadian fish and pronunciation of New Brunswick First Nations, and more ideas are percolating.

"Ideas come very quickly, between the two of us," Mazerolle said. "We can't get one project done before we have ideas for the next."

Childhood memories of day school

The fact that this artwork ever made its way into a book is a small miracle, one Peter-Paul attributes entirely to Mazerolle.

"She'd always say, 'Oh, your paintings are so beautiful.' She always encouraged me."

For Peter-Paul, art has been a source of healing and consolation for as long as she can remember.

"My grandmother taught me to paint, using berries and birch bark," she said. "I always painted on birch bark. Or wood."

Her voice softens when she speaks about her childhood days, warm when she speaks of her grandmother and shadowed when she speaks of her time in day school.

In Peter-Paul's youth, every Indigenous child in New Brunswick went to what were known as Indian day schools.

They were not New Brunswick's finest moment, and the memories are not easy to live with.

"I still remember how my teacher would knock me on the head. 'Anybody in there?' she'd say."

Peter-Paul chuckles at that recollection, then adds: "When you think or talk about sad thoughts, always try to give a laugh at the end, otherwise you want to cry."

There were the icy, unheated portables, so cold Peter-Paul's face would be numb.

There were the verbal and physical indignities, the slaps, the strap and far worse.

"There were two things I will never, ever forget," Peter-Paul said. "There was this dentist pulling teeth out of our mouth without any freezing or anything, and I remember him slapping my sister in the face. And the other thing was this teacher, in the winter … who would throw these kids outside, right onto the sharp ice."

Peter-Paul never told her family about how they were treated at school.

"None of us spoke about this," she said. "We all kept this as a secret."

For these reasons, and for others she doesn't allow herself to dwell on, the world anywhere beyond the safety of Metepenagiag was a place she avoided whenever possible.

There, she collected medicines from the forest, went for long strolls, taught her children and grandchildren the lessons of the elders and painted.

For years and years, she painted, everything from wildlife to what Mazerolle calls her abstract "cubism" series.

Then, in late May, the shattering news of the discovery of the unmarked graves of hundreds of former residential schoolchildren in Kamloops arrived.

A catalyst for change

That revelation was a catalyst. For traumatic memories, and for a way to help forge a new world for today's schoolchildren.

Mazerolle and Peter-Paul's book series project was already in the works when the news came out.

They were gutted by what they were hearing. They grieved and wept together.

But they also wondered if perhaps the harrowing revelation had brought the nation to a turning point — "a whole country of proud Canadians brought to their knees by the truth," Mazerolle said.

Against this traumatic backdrop, they hope the books and their illustrations can be part of a new beginning.

"Angela's artwork touches your soul," she said. "It is as much medicine as it is art."

For Peter-Paul, that medicine is not meant to be bitter. There has been enough of that.

"These books are all about the healing," she said. "We should not be angry with people, we are put on this earth to help one another. Because we are all one people. All of us."

To find out more about the books or to order them, visit Mazerolle's New Brunswick Reads page on Facebook, or email her at newbrunswickreads@gmail.com.

Do you have information about unmarked graves, children who never came home or residential school staff and operations? Email your tips to CBC's new Indigenous-led team investigating residential schools: WhereAreThey@cbc.ca.