The Bitter Aftermath of a Billionaire Murder Mystery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

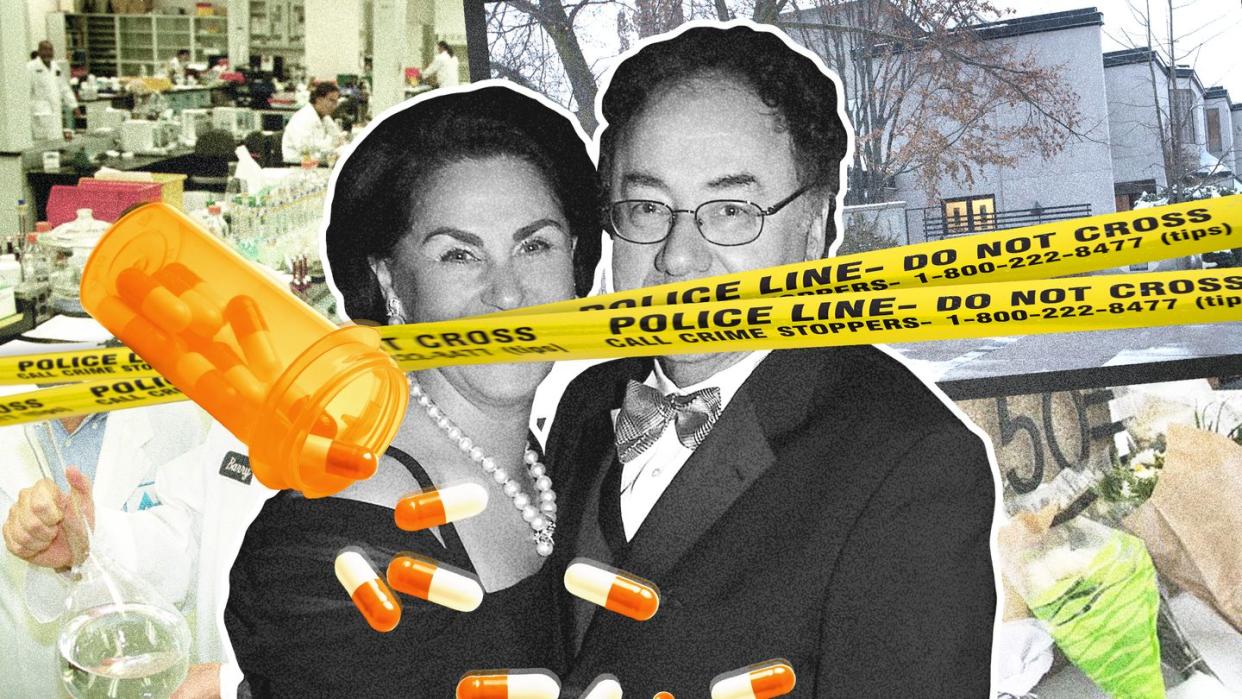

The house at 50 Old Colony Road belonged to the pharmaceutical billionaire Barry Sherman, one of Canada’s richest men. For nearly 30 years Barry had lived there with his wife Honey, and the two, supporters of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, were fixtures on Toronto’s charity circuit. Honey wanted to be closer to the city’s center, so in 2017 Barry, 75, and Honey, 70, put the home on the market for just over $5 million as they built a new $25 million mansion in Forest Hill, one of the city’s most exclusive enclaves.

One morning in December real estate agents turned up with a couple interested in the property. Their arrival had been preceded by those of the gardener and the housekeeper, who had noticed that the alarm was off and Barry was missing from his usual perch in the kitchen. The buyers were heading to the pool in the basement when one of the agents saw them. The Shermans were on the far deck of the pool, slumped over, in what the agent later described as “some sort of weird meditation or yoga” pose.

By the time the police arrived, rigor mortis had set in. The couple were seated side by side and fully clothed, and they each had a man’s leather belt wrapped around their necks attached to a metal pool railing about four feet high. Their arms were constrained behind their backs. The double homicide became a media sensation, riveting newspapers, podcasts, and Reddit, where theories exploded. How did a man worth $4 billion end up slain in such a manner?

Six years later the killings remain unsolved, no suspects have been named, and the public has moved on. But last December a niece and a nephew of the Shermans sued the deceased couple’s four children and others over one of several trusts, claiming the trustees were withholding information, and potentially millions. For a notoriously private clan, the lawsuit isn’t just an impolite breach of decorum. A public airing of dirty laundry—private emails, property deeds, wills, and financial records—prolongs a tragic family saga and adds another unseemly chapter to an enduring murder mystery.

Honey's Booboo

Like the house on Old Colony Road, the headquarters of Sherman’s company, Apotex, was dated. On the outskirts of Toronto, the company occupied a drab office park where chemists worked in white lab coats.

Sherman didn’t care much for appearances, or the trappings of wealth. He chided his number two at Apotex for wasting money on a Mercedes (even though it was an old model); Barry drove a decrepit Ford Mustang. When Honey gave him a sports car for his 50th birthday, he grumbled in front of their guests that she should take it back. What Barry loved, above all else, was work.

From the ground up, he had built Apotex into Canada’s top generic pharmaceutical manufacturer, accounting for a whopping one in five prescriptions filled in the country, often by beating rivals to the market. It was one of the first companies to produce a generic version of AZT, the first widely effective treatment for HIV, and one of the first to sell a generic version of Prozac. At its peak Apotex had annual sales exceeding $2 billion. Sherman, in his frayed dress shirts, cast himself as a sort of Robin Hood of the pharmaceutical world. Why shouldn’t patients get access to cheaper versions of life-saving drugs like Lipitor and Plavix? To Big Pharma he was closer to a thief, ripping off formulas they’d spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing.

Sherman was so consumed by his work he took it with him on vacations, even to the ski hill his family visited on winter weekends; he would pore over Apotex documents while Honey and the kids—Lauren, Jonathon, Alexandra, and Kaelen—hit the slopes. At the funeral Jonathon, the only son and self-described heir apparent, said when he played hockey or baseball as a kid his dad would show up only once or twice each season: “Those few games were my Stanley Cups and my World Series.”

With Barry busy, Honey often took her sister Mary Shechtman on family trips to Miami, where they owned a condo, or to Disney World, which Mary and Honey considered their “happy place.” Honey’s four children and Mary’s three grew close on these trips, and over time the families’ finances became entangled. In the early 2000s Mary’s husband Allen ran a mail order drug company for Barry based in the Bahamas (which faced allegations of unfair and deceptive practices) and then a jewelry firm Barry propped up with $32 million in loans, until it collapsed, to bankruptcy in 2014.

As for Mary, the Shermans supported her, as well, paying her to decorate homes, lending her money to buy property in Toronto and Florida, and, according to allegations in court documents, giving her about $10,000 a month in spending money. Every unhappy family may be unhappy in its own way, but the Shermans and Shechtmans were unhappy in very similar ways.

Although both Barry and Honey were penny-pinchers, Barry had no problem providing for his children or his extended family. He loaned Jonathon $125 million to start a self-storage business and a marina, and supported all his children with loans and property once they reached adulthood, giving them virtually anything they asked for, perhaps to make up for how little he had been around when they were young. Honey didn’t approve; she wanted the kids to become independent.

Her relationship with Jonathon was especially difficult. He complained that she was embarrassed he was gay. Also, as Toronto Star reporter Kevin Donovan recalls in his book The Billionaire Murders, Jonathon told a story at his parents’ funeral that was not hard to parse. During a family ski trip to Vermont, after a series of easy runs, Honey let Jonathon choose the next one. He picked a black diamond. “You were reluctantly gung ho,” Jonathon said. “I’ll never forget watching you wipe out on the first turn and slide down the entire run for everyone to see. It was effing hilarious. Until you made me march up and collect all your gear.”

Although Mary and her husband leaned on the Shermans financially, Mary shared her sister’s fears that her own children were entitled and scolded her son Noah in private correspondence for taking advantage of the Shermans. She had a particularly fractious relationship with Noah, who like Jonathon is gay. In a 2020 Shechtman family lawsuit involving a trust that Honey set up for the Shechtmans, Noah claimed that when he was in high school Mary tried to persuade him to go to conversion therapy, and she seemed to disapprove of his husband, who lived with Noah in the Shechtman home.

And yet Noah ignored his mother’s pleas to be more careful about asking the Shermans for money. A few months before the Shermans were killed, he emailed Honey and asked her if he could use her Saks credit card to buy a few things. “Of course. My pleasure!” Honey wrote back. When Mary found out Noah had used the card to buy Christian Louboutin and Brunello Cucinelli accessories, she was upset and threatened to remove him from the family trust that Sherman had set up for them.

“Everyone in the house shares the feeling that you would throw us under the bus for the chance to get to the Shermans and their money,” Mary wrote to Noah a year after the murders. “We each get that feeling individually. Since you don’t trust me, there is no reason for me to trust you.” According to court records, she allegedly had him removed as a beneficiary from her real estate portfolio, and the two haven’t spoken since 2019.

Pharma Palace Intrigue

In the immediate aftermath of the murders, much of the speculation centered on Apotex and its place in the underbelly of generic drugs. One industry insider told me that when Apotex opened labs in India in 2008, Sherman was knowingly entering a treacherous world. “I remember being in Hyderabad, and they tried to murder one of the VPs of a big pharmaceutical company while I was there,” this insider said. “They tried to murder him in his car, but it was bulletproof so they opened the door and killed his driver.”

Sherman’s reputation for infringing on patents and tying up rival companies in litigation was so notorious that Fortune reported in 1999 that one competitor raised the possibility of hiring private investigators to recruit Apotex employees as informants and even talked about planting cocaine in Barry’s car or ensnaring him with underage prostitutes. (The competitor dismissed the allegations.) Sherman had openly wondered if someone would knock him off. “For a thousand bucks paid to the right person, you can probably get someone killed,” he told author Jeffrey Robinson in the 2001 book Prescription Games. “Perhaps I’m surprised that hasn’t happened yet.”

In the months before the murders, Apotex faced unprecedented challenges on several fronts. The company was suing a former employee for stealing drug formulas; the U.S. Department of Justice had added Apotex to a list of generic drugmakers suspected of price fixing; Canada’s Supreme Court had just ruled against the company in a long-running dispute with AstraZeneca, leading to a settlement of more than $300 million. To top it off, Apotex’s chief executive had been accused in a civil lawsuit of receiving industry secrets from a former executive at a rival company whom he was sleeping with.

These crises partly explain why, when Sherman was killed, there were rumors that his various business ventures, including some outside Apotex, had something to do with his death. As outlandish as the theory of a hit organized by a rival drugmaker sounds, a source with intimate knowledge of the industry admitted that the thought had crossed his mind.

Speculating, this person told me, “Barry didn’t play the game. If you enter that world, where you’ve got plants in India, you play the game or you don’t. It would be like coming to New York in the 1920s and being like, ‘Hey, we’re going to do it this other way.’ ‘No, you’ll do it our way.’ ”

“Our way,” the source clarified, meant respecting territory and colluding on prices. Competing against a rival maker of generics could get you killed. And yet other sources with knowledge of the investigation say the Toronto police never seriously connected such a conspiracy to Barry’s murder. Meanwhile, tensions were rising among the surviving relatives.

Oh, Mary!

After the murders, it didn’t take long for the ties between the Shermans and the Shechtmans to come apart. Mary was one of the first people notified after the murders, and when she arrived in Toronto on a chartered plane from Miami she was distraught, yelling at one of Honey’s closest friends before others could calm her down. By the funeral, several days later, emotions had cooled. In front of 6,000 mourners gathered in a convention center, Jonathon announced the Honey and Barry Foundation of Giving.

“We would like our Aunt Mary…to help guide this foundation in a way that best honors our parents,” he said. But behind the scenes the Sherman children were growing weary of their relatives. It wasn’t just that Mary had billed the Shermans for the chartered jet; she was claiming that her sister had promised her hundreds of millions of dollars, as well as jewelry and real estate. “[Honey] wanted me and my children to get everything of hers,” Mary wrote in one email, according to Kevin Donovan’s book. “She knew the value of the entire estate would be minimal compared to what [Honey’s children] would inherit and none of [them] would need it financially.”

The problem was Honey hadn’t left a will, and while Barry had been planning to give Honey between $100 million and $500 million as “her own money” before his death, he never completed the transfer, according to court records. With both Shermans dead, and no will for Honey, the entire estate passed directly to the four Sherman heirs. “I cannot willy-nilly give my sisters’ inheritance simply because Mary claims it is hers,” Jonathon wrote in an email to his siblings.

Meanwhile, Mary kept telling people she “had to get to Disney World… It was like a salmon swimming upstream,” according to the Toronto Star. Only later would she realize Disney World was the last place the whole family—the Shermans, the Shechtmans, and all the kids—had been together. She billed the Shermans for that trip, too. The Sherman children cut Mary off shortly after the funeral.

Without access to the Sherman fortune, Mary told Donovan, her family was struggling. She was thinking of becoming a tour guide, and her husband Allen was driving an Uber to make ends meet.

Knives Out, Lawyers In

Today the rifts within the family extend far beyond the Sherman children and Aunt Mary, who along with her children declined to speak to T&C. Jonathon no longer talks to his three sisters, and in December two of Mary’s children, twins Matthew and Rebecca Shechtman, sued the Sherman children and other administrators of a trust worth more than $400 million. The trust, the suit alleges, was established in 2016 to benefit not just the Sherman children but also the children of Mary Shechtman and Sandra Florence, Barry’s sister.

It has just three trustees: Jonathon; Brad Krawczyk, the ex-husband of one of the Shermans’ daughters; and Alex Glasenberg, a decades-long confidant of Barry’s who runs the Sherman holding company, Sherfam. According to the lawsuit the trustees have breached their fiduciary duties by refusing to meet with the Shechtman twins or share details of the trust’s accounts. This is, at least in part, because Jonathon is no longer speaking with the other trustees. Lawyers for Jonathon, Krawczyk, and Glasenberg declined comment.

The Billionaire Murders: The Mysterious Deaths of Barry and Honey Sherman

amazon.com

$18.26

Shortly after the murders, dissatisfied with the Toronto police investigation (which initially concluded that the deaths were a murder-suicide), the Sherman children hired one of Toronto’s most famous criminal defense attorneys, Brian Greenspan, who has represented Naomi Campbell and Justin Bieber. Greenspan built an all-star team of retired detectives to conduct their own investigation, and they turned over their findings to the Toronto police in December 2019. A spokesman for the police declined to comment, “as this remains an active and ongoing investigation.”

Back then, during the Star’s attempts, spearheaded by Donovan, to unseal search warrant documents, the police said in court that the Barry Sherman estate documents were “embedded” in its homicide investigation. Four years later only one police detective remains on a case with no new leads, according to a source with knowledge of the investigation: “I think this one’s in the drawer.” Similarly, the December lawsuit is pending and unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

In 2019, 50 Old Colony Road was torn down. In the letter asking the city for permission to demolish it, the Sherman children said the home brought back too many awful memories. A year later a neighbor bought the lot and changed the address to 48 Old Colony Road, because who wants an address associated with an unsolved murder?

The listing last July, which described a premium location with a permit to build a 12,000-square-foot luxury home with an indoor swimming pool, eventually sold. The new owner is now hard at work building a house from scratch.

This story appears in the May 2024 issue of Town & Country, with the headline "The Bitterest Pill." SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like