Is the Black Lives Matter movement finally changing America’s legacy of racism?

The Minnesota state capitol has a number of boasts.

The current structure contains the second largest self-supported marble dome in the world, bettered only by St Peter’s in the Vatican. The building it replaced is among the places addressed by the slavery abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, who spoke here in 1873, three years after Minnesota passed a law extending the vote to black people, but who was nonetheless refused a hotel room because of the colour of his skin. (A national civil rights law passed in 1875 was never enforced.)

Despite having been to the twin cities of Minneapolis and St Paul more than two dozen times to visit my wife’s family, only this week did I visit the state house and grounds, when they become a site for people protesting the death in police hands of George Floyd.

For a visitor, the grounds have much to commend, not least a piece of art entitled Spiral for Justice, completed in 1995, and commissioned to honour another activist, Roy Wilkins. For almost 50 years, Wilkins, who died in 1981, led the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The work contains a separate piece for each of the 46 years he headed the organisation, along with some of his best-known quotes. One from 1967, says: “We do not yet have a society open to the free and full advancement of every citizen, whether or not his ancestors were slaves.”

These past two weeks, as the US has reeled from the death of Floyd and the protests sparked by the manner of his demise, the experiences of Douglass and Wilkins are central to the themes consuming the nation, even as Donald Trump threatened to send out troops and shoot looters.

In Douglass stood a man equal on paper, yet in reality the victim of stark discrimination. In the words of Wilkins, spoken 50 years ago, are contained the recognition that so much remained to be done.

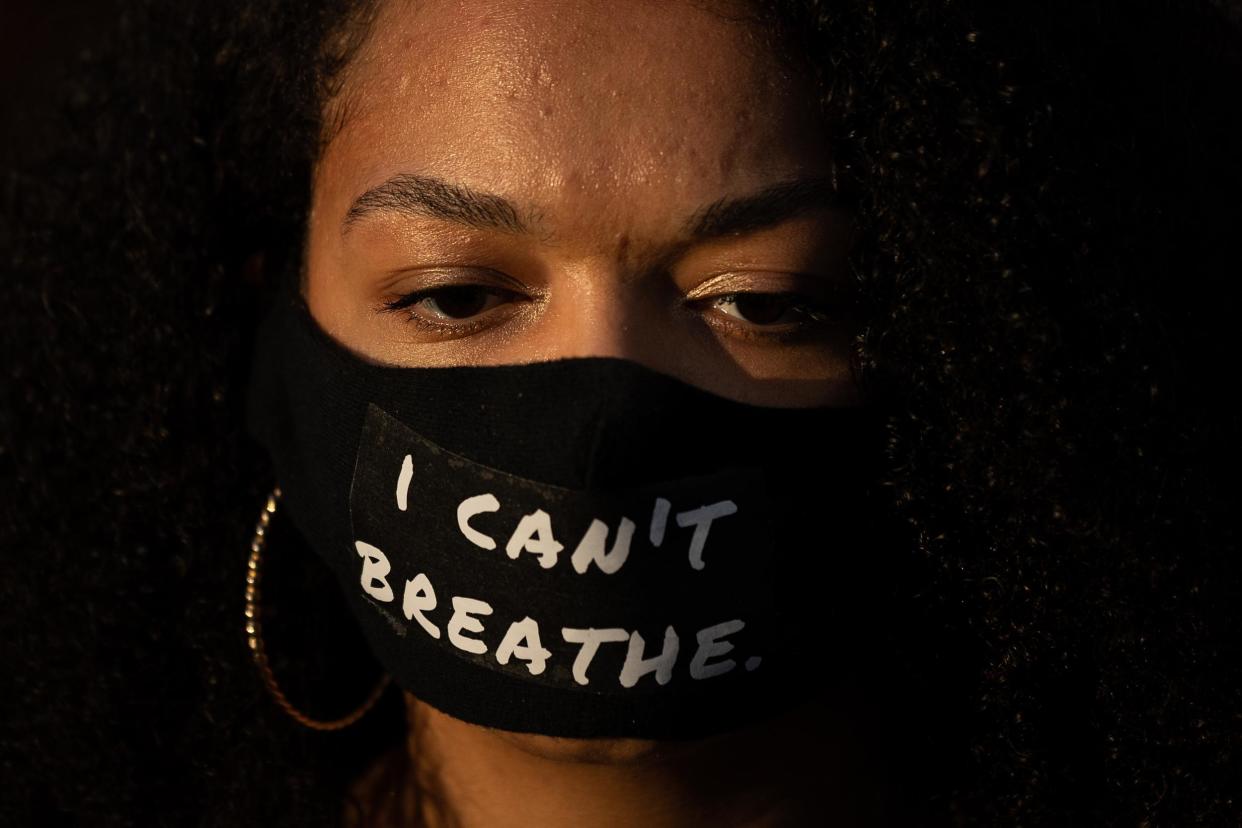

These were questions very much being talked about by the protesters outside the capitol. How was it possible that black men and women were being killed by the police at such a disproportionate rate, more than half a century after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act? Secondly, would the protests over the death of 46-year-old Floyd, filmed by onlookers as his neck was knelt on for almost nine minutes by a white officer, be materially different to those that followed the killing of people such as Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Freddie Gray? In essence, was this the moment that America would be forced to embrace real change?

Many of the protesters at the capitol insisted it was. “People were furious not just about the actions of police, but by the handling of the coronavirus pandemic,” said a 27-year-old activist who asked to use the name Mark White.

Schools and colleges had been shuttered, meaning people had time on their hands. Many people had lost their jobs, while others would rather protest than work for “poverty wages”. He added: “We’re not going away.”

Barbers better trained than police

The initial focus of protesters had been the arrest and charging of all four officers involved in death of Floyd, not just Derek Chauvin, the man videoed kneeling on his neck.

Yet, campaigners said this was not just a case of a few bad apples, but rather an insight into a criminal justice system riven by systemic racism. The way in which police forces were recruited, governed and regulated needed to be completely overhauled, said protesters. Campaigners said an attendant problem has been the increased militarisation of the police, often with small forces purchasing armoured vehicles designed for the armed forces.

The evidence of police malfeasance has been widespread. As the demonstrations spread to dozens of other cities, police officers have been filmed assaulting peaceful protesters, often in a manner that echoed the aggression shown during the arrest of Floyd.

In Buffalo, two officers were suspended after seriously injuring a 75-year-old man at a rally against police brutality. In Indianapolis, police have been put under the microscope after a video emerged showing four officers aggressively arresting a woman by striking her with batons.

Work by researchers such as Samuel Singwaye and the group Campaign Zero shows there has been a reduction in police killings of black citizens in forces that had sought to adopt ideas first recommended by a commission established by Barack Obama. These included greater community involvement, the use of body cameras by all officers, and the reform of contracts demanded by powerful police unions which permit the expunging of misconduct records as often as every 12 months.

Tracey Meares, a professor at Yale Law School and an expert on US police forces, said part of the problem was that there was no national standard. Unlike in Britain, there is no national academy to which recruits are sent. Rather, there are 18,000 different police and law enforcement organisations, each with its own standards on training.

On average, a local authority requires more training for a barber than a police officer. (In North Carolina, becoming a licensed hair-cutter needs 1,528 hours training, but just 620 to become a cop.)

“It’s true to say there have been some reductions in killings by police in urban forces,” she said. At the same time, the data suggests an overall increase in smaller and rural police forces.

“A really important conversation [we need to have] is not only about what we want police to do as emergency responders, but how should the state support its citizens in pursuit of their goals and projects,” she added.

Officials in Minneapolis have already vowed to “dismantle” the city’s force. A vote could be imminent.“Yes,” tweeted council leader Lisa Bender. “We are going to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department and replace it with a transformative new model of public safety.”

Nothing is a sprint

If the nation’s history is a guide to its future, the changes being demanded by protesters will come slowly, rather than in a cascade.

Perhaps partly because of the immediacy of a 24/7 media, it feels we live through many moments when we feel “things will never be the same again”. We think of the attacks of 9/11, the great recession of 2007-08, the election of Obama, the school shootings at Sandy Hook and Parkland.

In most cases, despite our certainty at that moment, there was not wholesale change. Many of the reforms promised against a wild and unregulated Wall Street have been eroded, school shootings remain as commonplace today and guns just as ubiquitous as when a troubled 20-year-old man shot dead 26 children and staff at Newtown, Connecticut, and the racist backlash against Obama’s legitimacy – not least by the man who would follow him into the Oval Office – did away to any notion we were living in a post-racial society.

That does not mean there has not been progress. Financial regulators have not been entirely de-fanged, Obama’s victory stands as a crucial landmark and he and his family continue to inspire millions. Meanwhile, community activists such as Moms Against Action, led by Shannon Watts, and March for Our Lives, founded by some of the students from Parkland, Florida, have seen success in securing gun regulation at a state and city level. Last November, a judge in Connecticut said the families of those who lost their children at Sandy Hook have the right to sue the manufacturer of the weapon that was used.

In June 2015, almost 50 years after protests triggered by a police raid on New York’s Stonewall Inn breathed new life into the gay civil rights movement, the country’s highest court ruled 5-4 in favour of gay marriage. (It came the same day as Obama broke into a startling rendition of Amazing Grace during a memorial service for nine African Americans shot dead in a church in Charleston, South Carolina, by a 21-year-old white supremacist.)

Of all those moments, it is perhaps the impact of 9/11 and a wave of anti-Muslim hate crimes and the fuelling of another sense of “otherness”, that remains most enduring.

Mary Owens, a physician who also directs the Centre of American Indian and Minority Health at the University of Minnesota, has been raising the alarm about the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus on Native Americans and people of colour. She has also highlighted reports showing that for young black men, dying at the hands of police is among the top half-dozen causes of death. One study found 1 in 1,000 black men and boys in America will die at the hands of police – 2.5 times the rate than that for white men.

Asked if black lives would ever matter in the US, she pointed out that to many people, black lives already matter enormously. “If you mean, when will the government care, it depends on what day you ask me,” she said. “Some days I think, yes, it will happen in my lifetime. Sometimes I’d say no.”

Not just police

Among the many emotions shared with The Independent by protesters – anger, fear, grief – one that was absent was surprise. The city of Minneapolis may skew Democratic blue and the state’s 5th congressional district may be represented by Ilhan Omar, but systemic racism and sharp inequality exist here too.

Because, for all the talk of reforming its police forces, America’s fundamental challenge of dealing with race goes much deeper.

More than 400 years after the first ships carrying African slaves were brought ashore at Jamestown, Virginia, too many white Americans struggle to acknowledge that the nation’s wealth and prosperity primacy among the world was built on such a trade.

Some seek to defend the Confederate flag as an innocent symbol of southern culture, ignoring the fact its popularity and adoption by many states and segregationists such as George Wallace came during the 1960s as an intentional statement in defiance of the civil rights movement.

When politicians such as one-time presidential candidate Kamala Harris make modest proposals to study reparations for such bondage, they are considered by too many to be too radical.

And yet this week, a Monmouth University poll showed 76 per cent of Americans, including 71 per cent of white people, said racism and discrimination were “a big problem”. It said 57 per cent believed the anger of protesters was “fully justified”.

The Black Lives Matter group was established in 2013 in response to the killing of black teenager Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year shot dead by a neighbourhood watch volunteer. One of the founders, Opal Tometi, told the New Yorker she believed the current protests may be different.

Yes. We are going to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department and replace it with a transformative new model of public safety. https://t.co/FCfjoPy64k

— Lisa Bender (@lisabendermpls)

“There is something about the economic conditions in addition to the lethal force we are seeing every day that makes this moment feel different, where people are making different kinds of demands,” she said.

Rachel Swarns, an African American writer who has spoken previously of America’s “hard history”, was struck by the large number of white people who joined the protests, a trend that began following the 2014 death of Eric Garner.

“It’s hard for me to find a light in all of this, but that feels like progress – that there’s a growing national awareness across colour lines that police brutality against black people has to be addressed,” said Swarns, whose work includes American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White, and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama.

“Technology is driving some of this. Unarmed black men being killed by police is nothing new, but now all of us are literally watching people as they’re being killed.”

At the same time, she pointed to data suggesting there had been no reduction in the wealth disparity between black and white families in more than 70 years.

“When will black lives matter,” responded Swarns, associate professor of journalism at New York University and a contributing writer for the New York Times. “It’s such a hard question. They obviously matter more. Our lives matter more than they did. But I struggle for words because, honestly, I don’t have the answers. I don’t have the answers for my readers, for my students, and for my children. I don’t have the answer for myself.”

A dialogue with justice?

All the while, some things appear to continue as normal. Or at least our pandemic-modified version of normal.

On Friday, a day after George Floyd’s family held a memorial service for him in Minneapolis, the president used his name while referring to better than expected unemployment figures, and an equal justice initiative.

“We all saw what happened last week. We can’t let that happen. Hopefully George is looking down right now and saying, ‘This is a great thing that’s happening for our country’,” said the president. “This is a great day for him. It’s a great day for everybody. This a great, great day in terms of equality.”

The remarks of Trump, who has been widely accused of racist and divisive rhetoric during his term in office, were widely denounced, not least by Joe Biden, the man who is all but certain to take him on in November's presidential election.

“He was speaking of a man who was brutally killed by an act of needless violence, and by a larger tide of injustice that has metastasised on this president’s watch,” Biden said. “He’s moved to split us based on race, religion, and ethnicity.”

“George Floyd’s last words, ‘I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe’, have echoed all across this nation. For the president to try to put any other words in the mouth of George Floyd, I frankly think is despicable.”

But is there a pivot towards justice?

The 47th element of the sculpture in the grounds in front of Minnesota’s state house consists of an obelisk adorned with an African relic. It is intentionally set on an axis with the state’s judicial building, that sits to the east of the capitol, as if Roy Wilkins, the man who led the NAACP all those years, was having a dialogue with the authorities.

The sculpture is the work of an African American artist, Curtis Patterson, who grew up in Louisiana, but now lives in Atlanta. As a teenager in Shreveport, he remembers a year after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, a white passenger on the bus asking the driver to tell him to stand at the back.

“The driver said ‘There’s nothing I can do about it’,” said Patterson, now aged 75. “And I refused to move.”

Did Patterson think things have changed since then, or even since his art work was installed?

“I think there’s been some advancement. I think we need to advance more, but I think there’s been an advancement,” he said. “I think, the mere fact that you see so many people being impacted by this crime, demonstrating throughout the country and throughout the world really. It’s not just black people, it’s people of all colours.”

He added: “I don’t think it’s going to be a change overnight. But from what I’ve seen happening, with the number of people participating, and the sincerity and the various ethnic groups involved, yeah, it’s going to have a stronger impact.”