How the Brexit debacle has complicated what it means to be British

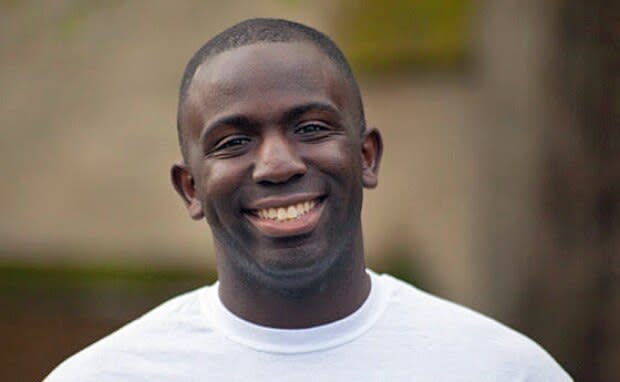

In the European Parliament this week, British Green MEP Majid Majid concluded a speech berating Prime Minister Boris Johnson over his handling of Brexit by asserting his own identity.

"I am proud to be British, Somali, African and a European," Majid said.

For Majid, Britishness is part of a complex and multifaceted identity. He told the CBC that "our lived experiences add up to who we are." For him, this includes his home for many years in Sheffield in the north of England, as well as his life as a Somali refugee and time spent as a child with his mother in a refugee camp in Ethiopia.

Many Brits would agree that Majid is representative of the multicultural island nation that Britain has grown into post-1945. But that sense of a multi-identity "Britishness" doesn't sit comfortably with everyone, and the question of what is the British identity has been brought sharply into focus since the deeply divisive referendum on European Union membership.

Anti-Brexit campaigner Femi Oluwole believes British identity "100 per cent" played a part in the referendum result. He said that British humour can be "self-deprecating," but that it is usually coupled with an insinuation "that we are this great empire."

But on June 24, 2016, Oluwole said he woke up to the realization that the joke about how Brits were better than everyone else wasn't funny at all.

"There was a nationalistic arrogance that came with the vote," he said.

Oluwole argued that since 2016, those who believe they have restored what it means to be British have in fact "made a significant part of the population, up to half, be less proud of being British."

Campaigners from both the Remain and Leave side admit — although not always openly — that British identity was, and still is, a key influencer in the Brexit narrative.

'No one would say we are European'

Oluwole's views are not shared in southwest Wales, in the county of Pembrokeshire, where Rayner and Carol Peett run a picturesque bed and breakfast in a 12th-century house, which is surrounded by farmland and mountains.

Carol is Welsh and Rayner, her husband, is English. Both are proud Brits who voted Leave. Neither believe that they have ever truly felt part of Europe.

"Frankly, down here, it doesn't register," said Carol. "No one would say we are European."

"The sense of being a part of a bigger community — I don't think that's ever really been adopted in the U.K. as a whole, and particularly in this neck of the woods," said Rayner.

"We're proud of our own," added Carol. "We're all for Brexit."

Sections of the British media that back Brexit have spun the line about the return of the blue passports, a reference to the colour they were prior to the UK adopting burgundy ones with "European Union" emblazoned on them. Leave supporters repeatedly talk about "taking back control."

Carol and Rayner agree that being an island nation is about having your own identity.

"We don't want things to change much," said Carol.

Immigration hasn't impacted greatly on these rural communities: they remain a largely white local population, with the exception of some "very good doctors and dentists that have moved in," Carol said.

'I am British and European'

The picture is very different just over 380 kilometres away, in the central English city of Leicester. A study by the London School of Economics in 2016 declared the city's Narborough Road the most "super diverse street" in the U.K.

They found businesses run by people from 22 countries of birth, including Uganda, Malawi, Kenya, India, Turkey and Iraq.

"I say I am British and European" said Ian Smalley, who has run a bookshop here for more than 30 years. "I like to be as broad as possible. Community is the watchword in our bookshop."

Smalley talks about the area benefiting from immigration. But recently, he has noticed many migrants from Poland, who opened businesses when it joined the EU, are now packing up and going home. Where once the British welcomed outsiders, Smalley now senses the opposite.

Christopher Browning, a reader of politics and international studies at Warwick University in Coventry, said Brexit sparked a debate about British identity.

He sees Europe as having become embedded in two very different visions of what being British is. Remainers feel close to Europe "because of the notions of cosmopolitanism, multiculturalism and an openness to the world."

Leavers don't see themselves as parochial. Instead, they "view Europe as a fundamental threat to core values of British identity, taking away notions of freedom and liberty."

And those who asserted an English identity above a British one were more likely to have voted Leave, Browning said.

A split identity

This is where we plunge into the split identity of Britishness. After all, Great Britain is made up of England, Scotland and Wales, with the United Kingdom being Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Kathleen Stewart is from Edinburgh and now lives in Glasgow after spending several years in England. Since Brexit, she has struggled with identifying as either British or Scottish.

"Previously, I would have said I was British and then Scottish, but I think that has now changed."

She said the inflammatory rhetoric surrounding Brexit is not something she wants to be associated with.

"To me, Scotland is showing itself as a more open, welcome and liberal country — and I can identify with that."

Stewart sees the Brexit debate as having reasserted old, nastier stereotypes of "Britishness," such as "beer-swilling British bulldogs" and "toffs in top hats," she said. Stewart fears that the Brexit path will lead to the break-up of the more than 300-year-old union.

Turning away from 'days of empire'

James Small, a third-generation farmer in Somerset in southern England, voted Leave because of his belief in a sovereign nation. He didn't want to be a part of the current structures of the EU.

Small identifies as English, and said the British are still a "liberal, tolerant society." But with the whole Brexit process, he acknowledged "we're not coming out of this covered in glory. We have to get away from the small proportion of population who will hark back to days of empire … We're not that anymore."

Amid all the questioning about self-identity, many people still want to become British. On Thursday, 52 people gathered at Brent Civic Centre in Wembley in northwest London for a citizenship ceremony. Among the group were 12 Europeans preparing to declare their allegiance to Queen Elizabeth II.

One of them was Michaela Mrockova, from the Czech Republic. She arrived in the U.K. in 2000 and has now spent half her life here. "My children are here, I have family here. [Becoming a citizen] is a way of feeling a bit more secure about being here."

To Bogna Klosinka, who is Polish and has been here for a decade, becoming British means "you are no longer an immigrant." She said she hopes to feel more accepted in society.

Caroline Di Dernardi Luft, a Brazilian who has been in the U.K. for nine years, said "one of the main factors about becoming British is so I can vote. I think it's really important at this point in time."

Holding up her certificate of British Naturalisation in front of a picture of the Queen, she was proud that despite the turbulent political situation, she can now call herself British.