Canada's methane emissions are likely undercounted, and that makes them harder to cut

Dave Risk has spent a lot of time hunting down methane, a colourless and odourless gas that's notoriously difficult to sniff out. Methane is a particularly damaging greenhouse gas that forms 13 per cent of Canada's total emissions, and the federal government has a multi-million dollar plan to reduce methane emissions to help meet its climate targets.

Risk heads the FluxLab at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, and his team of researchers drive out to thousands of oil and gas sites in Western Canada to measure methane at the source.

It's difficult work; researchers sometimes put in 12 hour days, driving all day to visit numerous remote sites. They have to spend weeks in the field, visiting each site multiple times to collect measurements. The idea is to get a more accurate picture of how much methane Canada is emitting — which is likely much more than the government's official estimates.

FluxLab's latest paper, which involved measurements at 6,500 sites, found that Canada's methane emissions are about one-and-a-half times the official estimate.

Another report just last year, by the government's own scientists, found that methane emissions are about double the official estimate. That study relied on measuring methane in the atmosphere across the country.

"I know without a doubt that scientists in Canada and abroad have known probably for 20 years ... that emissions were underestimated," Risk said.

Better accuracy matters, both because of the role methane can play in trapping heat in our atmosphere, and because of the need to measure whether methane reduction efforts are working.

Estimates vs. measurements

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) estimates methane emissions in the oil and gas sector by mostly relying on mathematical modelling based on a small number of field measurements. The agency is constantly updating its methodology and the process to estimate methane is in line with international obligations, but researchers say it's time to move to actually measuring methane rather than estimating.

"Right now the inventory is based on estimates that are over a decade old and they're proposing using new estimates, which is a step forward, but it still uses estimates," said Jan Gorski, a senior analyst at the Pembina Institute who studies methane emissions from the oil and gas sector.

"Eventually where we want to get to is to actually use real field measurements of methane. So looking at what are the real levels of methane that are being emitted right now in the field."

In a statement, ECCC said that might happen, but didn't offer a timeline.

"In the future, atmospheric measurements may be used to validate existing estimates in a way that was previously not possible," the statement reads.

A much more potent greenhouse gas

Methane, the chief component of natural gas, is released during oil and gas extraction and leaks into the atmosphere from the various pieces of equipment on an oil and gas site, such as storage tanks, valves, fittings, and pipelines. The purpose of methane measurement technologies is twofold: to detect leaks so they can be fixed, and to figure out if those efforts are paying off in methane reductions in the atmosphere.

Methane traps 70 times more heat over a 20 year period than an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide, making it a much more damaging greenhouse gas. But methane also only remains in the atmosphere for about nine years, meaning reducing its emissions now would have more immediate positive benefits for the environment.

Canada's plan is to reduce methane emissions 40-45 per cent below 2012 levels by 2025, and it's doing this with regulations to monitor and fix or modify the various pieces of equipment on oil and gas sites that leak the gas. The federal government also has a $750-million fund to help companies that are trying to reduce methane emissions over and above the regulations.

Fixing the right things

But knowing which pieces of equipment are leaking methane, and therefore should be targeted, is a challenge. Matthew Johnson, a researcher at Carleton University and one of Canada's leading experts on emissions from the energy sector, has been studying a new technology that could help detect methane with unprecedented accuracy using laser technology.

"You can't reduce what you can't measure. And if we're talking about 45 per cent in a near term … and net-zero by 2050, we better be measuring how our progress is going or we won't make it," he said.

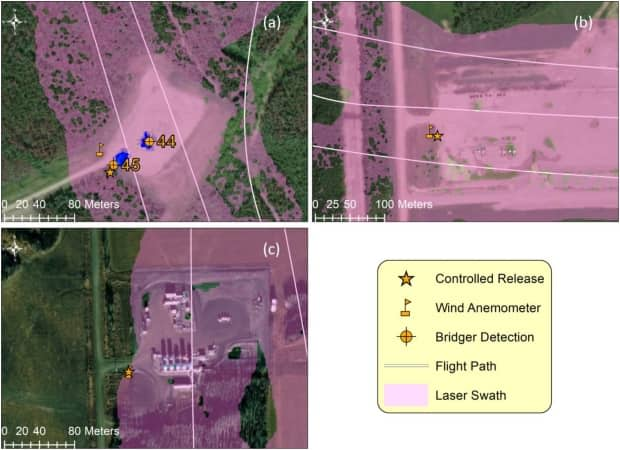

Johnson's team tested the new laser technology in northern B.C., where they flew a plane mounted with the imaging unit over oil and gas equipment. The plane can fly over multiple sites in a short amount of time, making it quicker and cheaper than visiting those locations by road and taking measurements at each site. The result is images that show where the colourless gas is being released.

More importantly, by being able to detect which exact pieces of equipment are emitting the most methane, the technology can help refine methane regulations.

"By being able to fly hundreds of facilities, see sources within facilities and to quantify, you can change how inventories are created to make them more accurate and more reflective of what's really out there," Johnson said.

"That allows operators to make decisions about what action needs to be done to get the most methane out of the air and allows regulations to be developed to focus on the things that matter, so that dollar for dollar, we're doing the best we can."

Government planning improvements

ECCC released Canada's latest National Inventory Report on April 12, which contains details on total greenhouse gas emissions for 2019. According to the report, estimates of methane emissions remained largely unchanged from the previous year. The report noted that "important method improvements" will be made to methane estimates next year.

The government plans to report on the efficacy of its methane reduction programs sometime in late 2021. Both Risk and Johnson are hopeful that their work will be used to improve the way methane is measured, and ultimately the regulations to reduce it.

"What's exciting about this technology is just that we can see sources and quantify them in a very efficient way, and that just hasn't been possible before," Johnson said.

WATCH | Cutting methane emissions requires better measurement: