Canadian ranchers, farmers get serious about security

It took a stolen truck, a police chase and a smashed gate to get Bruce Stigings to start thinking about security on his southern Alberta farm.

Last September, police stopped a stolen vehicle in the nearby town of Innisfail but the truck took off, with the police in hot pursuit.

The chase wound down country roads and through a field next to Stigings's home before finally ending when the stolen truck smashed into his front gate

The impact left Stigings on the hook for thousands of dollars in damage and left an impression on more than just his gate and wallet.

These days, cameras are always watching Stigings' acreage, and the retired farmer can check on his property from anywhere just by swiping a few buttons on his cellphone.

He does it at least two to three times a day, he says.

"As often as I feel I need to, depending on what's going on in the area," he says.

And what's been going on, according to Stigings, is a noticeable increase in crime.

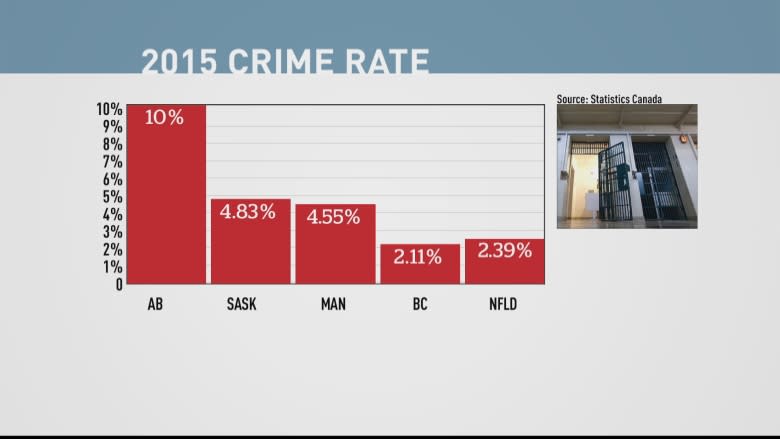

In fact, data from Statistics Canada shows crime is on the rise in many parts of rural Canada, led by a 10 per cent bump in rural Alberta in 2015.

More farmers and ranchers are now looking for ways to protect their property.

Stigings says he spent about $2,000 on a security system that includes cameras and monitors inside and outside his home.

And he says many of his neighbours are considering taking similar steps after their own brushes with criminal activity.

"We have a neighbour that we rent land to and they have been broken into twice in the last two years — had their car stolen, a gun stolen. It is serious when that is happening."

Break-ins, gunfights

Some of those residents end up calling Chris Sobchuk of Allan Leigh Security and Communications in Brandon, Man.

He says an increase in rural crime has meant a boom in his business.

"We do about 12 trade shows a year and I would say that at least 50 per cent is going towards farmyard security, where it used to be three, four, maybe five per cent.

Sobchuk says he hears many stories from customers about everything from break-ins to gunfights on rural properties in Manitoba.

"They are having fuel stolen. They have ATVs and snow machines. Their shops are being broken into," he says. "People have been telling me they have been having home invasions — like, they have actually been locked into rooms in their house."

Sobchuk believes that the increase in rural crime is due in part to the downturn in the energy sector, which has left thousands of young men in Western Canada out of work.

One province over, a group representing rural communities is doing more than installing cameras.

At their annual general meeting, members of the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities, or SARM, voted to push Ottawa to expand the right to defend property in Canada, citing fears over the growing incidence of crime in their communities.

Feeling 'threatened'

SARM president Ray Orb said that the motion passed with more than 90 per cent support.

"Our members are feeling a little bit threatened," he said. "They are worried about their own safety and the safety of their families."

But increasing a landowner's right to defend their property is a touchy subject in Saskatchewan, where a farmer is awaiting trial for the shooting death of a First Nations man on his land.

Gerald Stanley is charged with second-degree murder in the death of Colton Boushie after the 22-year-old drove onto Stanley's farm near Biggar, Sask., last year.

But Orb says that while his group wants landowners to have more leeway to defend their property, he doesn't want to see more gunplay.

"We are not condoning that ratepayers take action against perpetrators but instead they call the RCMP," he said. "Or if they have a rural crime watch program, that would be their first contact."

Stigings likes the initiative from his neighbours in Saskatchewan and said he would like to have more rights when it comes to defending his rural home from criminals.

"I believe that people should be able to protect their own property," he said. "The laws shouldn't be there to protect the guilty, they should be there to protect the innocent people."

But Stigings adds that what he would really like to see are tougher sentences that keep criminals behind bars longer.