Cannonball Cricket: the indoor revolution that failed to take off

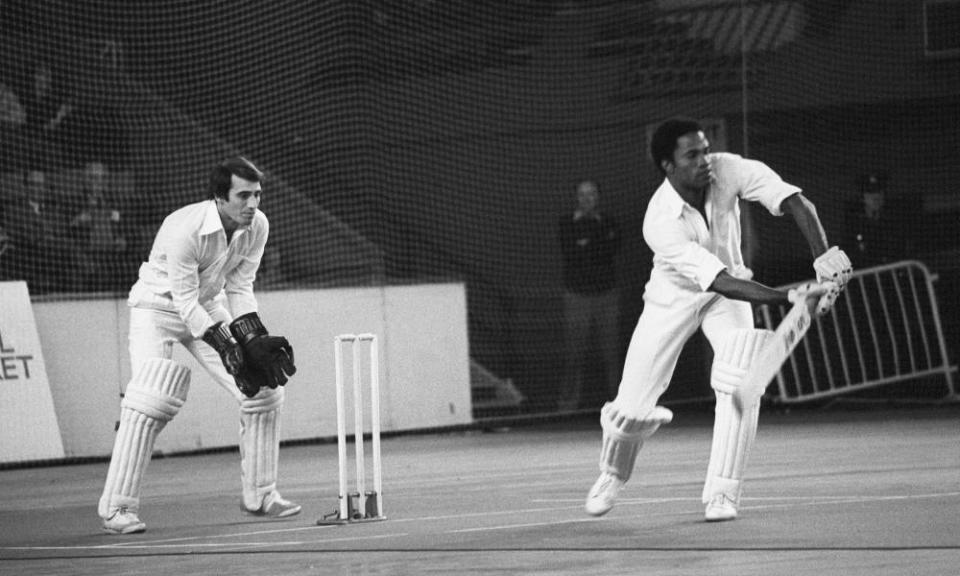

It was in this week in 1985 that the Guardian first reported on a new form of indoor cricket, apparently set to take the nation by storm. A centre had opened in Wellingborough, another in Ipswich was following the week later and two courts at Lord’s were coming on stream the week after that, to add to venues already open in Hounslow and Peterborough. The ambition was for 150 indoor centres to open within three years. It was, according to Gordon Jenkins of the Lord’s indoor school, “wonderful for cricket”.

The following year the journalist Tim Heald published a book called The Character of Cricket, for which he travelled across England and Wales, talking to people involved in the game at various levels to establish a snapshot of the sport as it headed towards the final years of the century. “As far as cricket is concerned I think I may have seen the future,” he wrote of a visit to one of these centres. “I found it in a converted warehouse in Hounslow. This is the home of Cannonball Cricket – ‘It’s Fast! It’s fun! It’s for everyone!’ It was a warehouse, but now it is 25,000 square feet of indoor cricket ‘courts’. Its popularity is growing so fast that any claim made in this book will be out of date by the time it is published (unless I am hopelessly wrong and the whole thing has gone bust).” Colin Lumley, the Australian-born real tennis professional who managed the Hounslow centre, told the Times in 1985 “there are 250,000 Australians who play the game every week – and I think it will soon be as big here”.

Related: Ian Ridley’s memoir of coping with grief is a reminder of cricket's soothing qualities | Andy Bull

Interest did indeed grow, and the number of facilities with it, but it was not sustained. Nobody has played indoor cricket in Hounslow for nearly three decades. Thirty-five years after a Guardian report that trilled “the bastardised version of our national game being marketed as ‘cannonball cricket’ seems to be a hit” there are only four centres offering this form of the game – eight-a-side, tension nets, now known as Australian or action indoor cricket – in Great Britain: in Leicester, Birmingham, Nottingham and Derby.

“I set it up because I’d seen how well the sport was doing in Australia, and I just saw the potential,” says Lumley, whose financial interest in the game ended after he sold up in 1989. “But it was hard to get the right properties at a realistic price. We set another one up in Swansea, and we wanted to set up smaller units, two-court centres, but we couldn’t find the right properties. You need quite a big area. In Australia you’d buy a block of land and build something to the right size, but that was unaffordable here and with the rates we were being charged for the right properties you had to get so many people on court to make the numbers stack up, and indoor cricket is mainly an evening and weekend thing. The rent per square foot and the availability of the right properties was the real killer.”

Anish Patel played first-class cricket for Loughborough University and minor counties cricket for Lancashire, and now runs one of those four remaining centres, in Birmingham. “I think there were 60 or 70 centres in the UK at one stage,” he says. “It was a thriving sport. In the late 1980s and early 90s all the professionals played it. But higher costs and taxes, business rates and those things, meant it became a non-sustainable thing to run.

“You need multiple revenue streams to make it work – the centre in Birmingham has the cricket, it’s got a gym, it has soft play for kids and it’s got a trampoline club. I just want to see the game grow. We want to provide juniors with the opportunity to play cricket all year round. We know our place, it’s not to compete with summer cricket – it’s a top-up in the winter.”

Internationally, the sport continues to thrive. The thousands of Australian participants that inspired Lumley to bring it to the UK in the 1980s have not gone anywhere (Cricket Australia’s latest audit did find a 6% drop in participation, but blamed it on Covid-19 and summer bushfires). It is widely played in New Zealand and South Africa, and increasingly popular in India. Had Covid-19 not intervened a World Cup, due to be held at the Casey Stadium just outside Melbourne, would have finished on Sunday. Australia would have won. They always do.

Patel was England’s captain at the last World Cup, in 2017. “It’s the only version of indoor cricket where there is a World Cup,” he says. “I took it up when I was 18, after watching the World Cup that was held in Bristol in 2007. Fundamentally the biggest drawback is that it needs a specific area and specific netting. The nets have to be able to support people jumping into them, and people can’t play the sport without that. We’re trying to find ways of giving people an adapted version, which will allow them to play in any sports hall with adapted rules. I think there is a future for the sport. There’s no difference in technique to cricket – it’s strong cricket shots, played with a full face. It has certain advantages over six-a-side indoor cricket, because everybody gets a bat, everybody gets a bowl – even the keeper has two overs.”

Many of Australia’s best-known cricketers, including Mark and Steve Waugh, Michael Clarke, Brad Haddin and Aaron Finch, came through indoor cricket. Cameron Boyce, who played seven international Twenty20s for Australia, had hoped to be in his country’s team for this year’s World Cup. Jesse Ryder, veteran of 18 Tests and 48 one-day internationals, played for New Zealand in the last one. A handful of English players are attempting to bridge the gap from the indoor game to the professional including Luke Hollman, who excelled for Middlesex in this year’s T20 Blast having already represented his country at two World Cups – at 21-and-under level indoors in 2017 and at under-19 level outdoors a year later.

A year ago many working in the game in the UK were feeling renewed optimism for the future. It may soon return, with 2021 now scheduled to feature not only the rescheduled men’s and women’s senior World Cups and the 21-and-under tournaments that are played alongside it, but the triannual Junior World Series, scheduled to be held in South Africa. Organisers are hoping to send as many as eight teams across the world to represent England in 2021. First, though, they must negotiate a winter likely to be complicated by Covid protocols and local lockdowns.

“In the winter it’s normally frantic,” says Patel. “Prior to coronavirus, the leagues were full with a waiting list of teams to play. What we find is when people start to play, they don’t want to stop. I can’t tell you why it hasn’t picked up more over here. Being in a country where it rains a lot, I don’t understand. But hopefully it’s growing again.”

• This is an extract taken from The Spin, the Guardian’s weekly cricket email. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions.