Carafem's 'spa-like' abortion clinic part of new U.S. trend

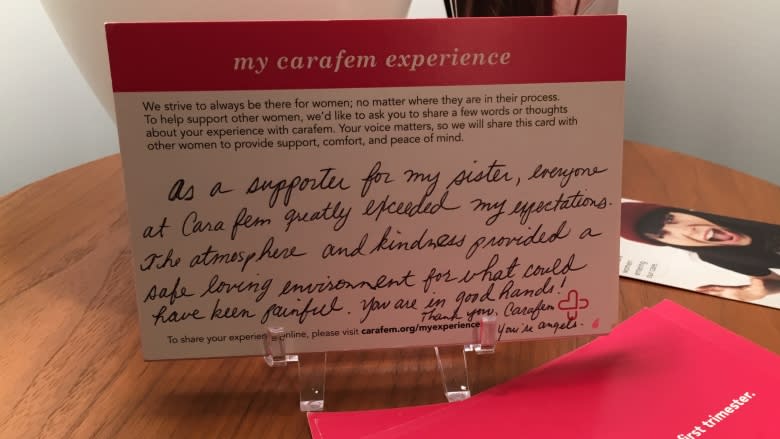

The comments, handwritten on pink cards in the welcome lounge, praise Carafem's "quick service" and its "classy, chic and modern atmosphere."

The reviews could describe any of the salons or boutiques sharing the same tony strip in the Friendship Heights district of Washington, D.C. But Carafem, with its natural-wood finishes and cheery wall art, offers a unique service to women here: Safe, anxiety-free abortions.

"We wanted to be a voice that women could hear unapologetically standing behind health care," Melissa Grant, Carafem's VP of health services, said recently from the clinic's flagship office.

"We'll have flowers, there's music, there's no harsh medical smells, images on the walls are of people smiling. We're trying to maintain an experience that is as friendly and comfortable as it possibly could be," says Grant, a former director of Planned Parenthood.

Carafem, which opened in April 2015 and specializes in the abortion pill for early-term pregnancies, represents a shift in abortion-care ideology — one that aims to "de-medicalize" the whole process.

Carafem practitioners do not perform surgical abortions. And anyone coming for a consultation might be offered a robe or a cloth drape to wear. An accompanying friend or relative might warm their hands around a cup of tea, or be invited to sit on a purple sofa with throw pillows while discussing intrauterine contraceptives.

In the examination room, the obstetric table is set up as a chair.

Spa-like atmosphere

Those details are small yet crucial. Grant says it contributes to the "spa-like" feeling the health centre aims to achieve by countering "a social myth for clients that abortion clinics are these scary, frightening places."

Carafem also refers to patrons as clients, as Grant believes the word "patient" can wrongly suggest people with unintended pregnancies are sick.

While Carafem hasn't been a particular focus of pro-life activists since its opening, it is arguably at the centre of the next big battleground over abortion access in the U.S. — the fight to remove barriers to abortion-inducing medications.

Women who want to terminate pregnancies in several states now face restrictions in obtaining the drug mifepristone, the so-called abortion pill, also known as RU-486, that was approved for use in Canada last summer, because of strict rules that evidence-based science has slammed as outdated.

The U.S. approved the use of mifepristone back in 2000, but the rules set out at the time for its use are said to have created higher costs, uncomfortable side effects and, sometimes, incomplete abortions.

These rules also prohibited a woman from taking mifepristone in the privacy of her home, which reproductive rights groups say amounts to a virtual ban on medication abortion.

The Carafem model removes most of these restrictions.

It is also a striking departure from the sterile environments at some abortion centres, says Steph Herold, co-founder and managing director of the Sea Change research program, which is trying to erase stigma around sexuality and reproduction.

Such clinics — with their security guards, metal detectors, barred windows, buzz-in protocols and cash-only policies — can unintentionally reinforce abortion shame, she says.

Still, at a time when some reproductive health-care workers feel the need to wear bulletproof vests, balancing security with a relaxing setting is a challenge that isn't lost on Grant.

November's fatal shooting at a Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs brought that into sharp focus.

"Carafem makes the safety and security of our clients and staff our highest priority. It's a part of everything we do," Grant said.

Although Grant did not wish to discuss security specifics, the Carafem office is located in a nondescript medical building to maximize privacy. There is no signage outside, only a suite number in the directory of the lobby.

Those were deliberate choices.

Advocates for better abortion access agree that one effective way to end stigma is to reassess how the clinic environments looks and feels.

"Clinics cannot and should not be fortresses," says Nikki Madsen, executive director of the Abortion Care Network.

Alleviating, not increasing stigma, is part of providing respectful, effective care, she said. "This cannot be done in a bunker, or in an atmosphere of fear."

Hot tea, blankets and journals

While Carafem is not the first of its kind to offer a more holistic approach to abortions, Herold says it's among several providers exploring new ways to "normalize" a procedure that more than a million American women undergo annually.

The Whole Woman's Health series of clinics, which began in Texas in 2003, features lilac hallways and dim lighting to set a soothing ambience. Rooms named after prominent women have walls that are stencilled with empowering quotes.

"We have candles, herbal teas brewed to help with cramping and nausea, fleece blankets in the clinic," founder and CEO Amy Hagstrom Miller said. "We have journals in our waiting room and our recovery room so women can write about their experiences and write to each other."

When she founded the first Whole Woman's Health centre, Hagstrom Miller also envisioned a "spa approach" involving option "menus" that allowed a woman to choose the kind of lighting or sedation she'd like, and whether she would like her partner in the room with her.

Whole Woman's Health now has eight clinics in five states, most recently bringing its care model to New Mexico and Illinois in 2014.

Carafem, which is a non-profit organization that accepts donations to cover the cost of its services, is also considering expansion.

None of this gives any comfort to pro-life activists.

Day Gardner, President of the National Black Pro-Life Union in Washington, expressed outrage that any organization would so openly welcome normalizing abortion care.

"Abortion is not a spa-like procedure for mother, and most certainly not for the child. Name another spa where a person is purposefully killed. Name another spa where two living beings go in but only one comes out," she said, calling the spa concept "horrendous."

Grant said she generally has "nothing to say about those who disagree with a clients' right to choose." Most importantly, she believes women and men want their reproductive decisions to be respected and dealt with in a place they find comforting.

"We wanted to talk about abortions in a way that didn't feel like we had to speak in hushed tones, or that people would feel ashamed of the services," she says.

That matter-of-fact approach is reflected in Carafem's advertising.

Pink billboards around Washington streets and metro stations have sprung up, proclaiming: "ABORTION. Yeah, we do that."

The messaging frames abortion care as a common need for many women, said Carin Postal, the marketing strategist who helped design the ads.

"It was trying to hit at the reality…[and] to show the client that this is normal. This happens," she said, noting that one in three women experience abortion care in their reproductive lifetime.

The ads were the subject of some controversy last spring, drawing criticism from pro-life groups that decried what they deemed to be an overly-blithe tone.

Grant says Carafem has no intention to downplay the gravity of making decisions about birth control and abortions, only to encourage open discussion of the options.

That discussion extends to how Carafem's care model might evolve over time. Changes will depend on the feedback they get from their clients.

"It wasn't just about learning about what clients didn't want, it was learning about what they did want," Grant says. "What we do right now may get changed depending on what women tell us."