By Chance: Switched at birth, they were brought together again by coincidence

Imagine this: Your first memories, your early years with your brothers and sisters, and parents and grandparents — they all should have been someone else's. And the reason why is pure chance.

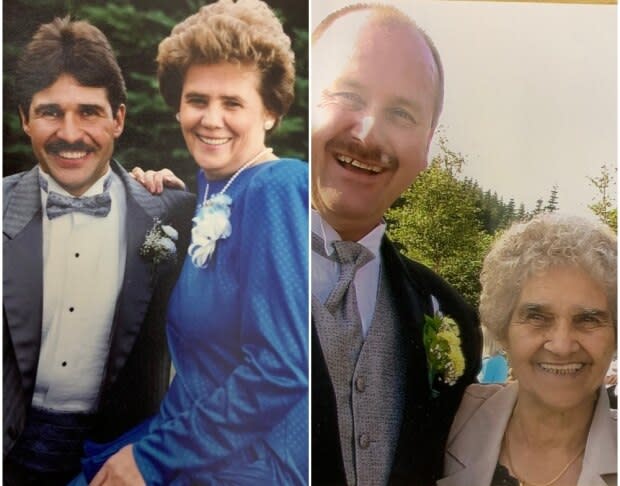

Clarence Peter Hynes and Craig Harvey Avery were born in the Newfoundland town of Come By Chance — a name that perfectly describes their mixed-up lives.

Both were born at Walwyn Hospital, Come By Chance's cottage hospital, on Dec. 8, 1962. Somehow, the two were sent home with the wrong families.

Avery went to Hillview with Hynes's birth parents. Hynes was sent to St. Bernard's with Avery's birth parents.

On television or in literature, it's a setup for prince and pauper stories, where the child of a wealthy or aristocratic family is switched at birth with a child from a poor family.

Possible takeaways: Fate is a lottery or a poker game. We should play the hand we were dealt. The natural order finds a way to restore itself.

He said 'Come By Chance' and right then, when he said that, I just thought that, 'You know, something is not right.' - Tracey Avery

But when it actually happens, it's not so tidy. It's painful.

"It's unbelievable that something like that could happen. These people are supposed to be professionals and do what they are supposed to do, and it was just, to me, utter neglect," said Avery.

"The hardest part is not knowing. How did this happen? Why did this happen?"

Similar upbringings

Being robbed of growing up with his birth family is what hurts the most, said Avery.

"You never got to sit down with your parents. You never got to be there for special occasions. Your brothers and sisters … you never got to grow up with them. It's hard," said Avery, swiping away tears. "It's very hard."

Avery's and Hynes's families were similar in various ways. Both are rooted in rural Newfoundland. Avery is third youngest of seven boys and one girl. Hynes is one of three brothers and four sisters.

"I grew up in a good, happy family. Me and Clarence grew up in probably equal families. Good families. Good upbringing. Good parents," said Avery.

But that doesn't mean what happened doesn't matter.

"I had a wonderful life. I wouldn't change my life that I had for nothing, but it still wasn't right," said Avery.

Early questions

There were hints decades ago.

Tall, blond and fair-skinned, Avery grew up reminded he wasn't like his dark-haired brothers and sisters.

"They were all dark, and I was so light and I was bigger than all of them," he said.

Questions were raised about Hynes too.

Working on the Hibernia oil project in the 1990s, Hynes was often told he resembled the Avery brothers. Sometimes he was even mistaken for one of them.

But Hynes dismissed it all until the evidence was too strong to deny.

"I didn't want to know."

Enter Det. Tracey Avery

What happened in 1962 might have remained unknown if not for Avery's wife, Tracey, who connected the dots and asked the questions.

Four simple words, "Where were you born?" exposed a secret — a mistake? A cruel joke? — that irreversibly changed the course of two families' histories.

That question might never have been asked but for a series of unlikely, chance events and circumstances:

During a period when thousands of people left Newfoundland, most of the Avery and Hynes families stayed.

Both Hynes and Craig Avery worked in oil industry-related jobs

Both of them ended up at Bull Arm working on the Hebron project in 2014.

They weren't working side by side, but they were in the same building, where their paths must have crossed many times.

Then there was a fourth, crucial, event: Tracey Avery was hired at Bull Arm too.

Her first day there, she was struck by how much Hynes resembled her husband's brother, Clifford Avery.

"She came to me and she said, 'Craig, do you know there is a fellow who works here who looks just like one of your brothers?'" said Craig Avery.

But Hynes, a welding foreman at Bull Arm, had also heard it from other people.

"There were a couple of buddies who came to me also and said there's a fellow down there that looks like my brother, and he even got the same spot on his moustache that you can see."

He had never noticed a resemblance himself: "He looked different with a hardhat and safety glasses on."

Hynes asked Tracey Avery for her husband's last name. When she told him, he said he'd been told he had looked like the Averys as far back as 1993.

"But you just brush it off because there's always somebody who looks like somebody," said Hynes.

But it lingered in the back of Tracey Avery's mind until another clue made it impossible to ignore.

Birthday surprise

One day, at a birthday celebration for Craig Avery at Bull Arm, Hynes told Tracey Avery it was his birthday too.

"So right away, I'm like, 'Where were you born?' and he said, 'Come By Chance,' and right then, when he said that, I just thought that, 'You know, something is not right,'" said Tracey.

For her husband, the questions raised by the apparent coincidences weren't entirely out of the blue, but learning the two men shared a birthday and a birthplace took those questions to a different level. Many nights, the Averys sat up in bed talking about it. What did it mean? How could they learn more? Should they look for answers or leave it alone?

It was unbearable. Craig Avery looked online and found articles about people who had been switched at birth in Manitoba.

"I saw this had happened in Manitoba and then I wondered if that was us too. Could it be that we did get switched?" asked Avery.

They decided to keep looking for answers. Avery went to his family doctor and took things a step further with a DNA test, comparing his DNA with the DNA of one of the brothers he grew up with.

The test showed Avery and a man he had always called his brother did not have the same father.

But what did that mean? There were a few possible answers, but Hynes's parents and Avery's parents were already gone. Hynes's DNA would help clear things up, but when Avery told him about the results, Hynes was overwhelmed.

"I didn't want to believe it at the time and it probably took me a couple of years to get something done myself," said Hynes.

Eventually, he had his DNA compared with the same man Avery had.

"It came back that my DNA was a 100 per cent match with his brother," said Hynes.

It was a discovery he couldn't accept.

"I didn't want to know at the time. I went through a hard time a couple of years. I broke down with all this playing on my mind. I had to go to my doctor and everything, but I don't know.… It's not getting no easier."

Then, to further confirm what was becoming clear, Avery had his DNA compared with one of the brothers Hynes grew up with. They were a 100 per cent match. Avery and one of the men Hynes thought was his brother had the same father.

At that point, neither could deny what had happened — and it hurt.

"It wasn't easy," said Hynes, understating the impact; he fell into a deep depression.

Sleepless nights

He couldn't leave his home for weeks. Some days, he couldn't get out of bed. Other days, he fought to get as far as the kitchen, where he stood over the sink and cried.

Hynes was dealing with something few people have experienced. It's like discovering you were adopted, but it's different because it wasn't a choice. It's a blunder with irreversible consequences.

"It was definitely life changing," said Avery. "You grow up with a family for 56 years and then all of the sudden you learn that that's not your family. Your parents are gone. They've passed on and they didn't know nothing about it. It's a lot of sleepless nights."

In the early-morning hours, his mind still swims with unanswerable questions.

"You always think about, 'Where would I be today? How would I have grown up?' There's always what-ifs.… How would your life have been different if you'd grown up with the family that you should have grown up with? What were your real parents like?"

It's been a hard road. A very, hard road. - Craig Avery

With both men's parents gone, that last question can never be answered — and that's the hardest part, said Avery.

"It's been a hard road. A very, hard road. What hurts a lot is knowing that your parents are gone to their graves and they had no idea, and they never will, and we never, ever got to meet our parents or grandparents," he said. "This deprived us of our families for 56 years."

It has caused a lot of agony — pain that persists.

"Some of my family are still dealing with it now. It's very hard," said Hynes.

It's so hurtful. It's like your heart is broken all of the time. - Craig Avery

Avery said it's hard to describe to someone who has always known their parents what it's like to learn that you never met your birth parents.

"It's so hurtful. It's like your heart is broken all of the time. Every day, no matter what you are at, you're always thinking about this," he said. "When I wake up in the morning, this is the first thing that's on my mind. When I go to bed at night, this is the last thing that's on my mind before I go to sleep."

Sometimes those thoughts turn dark.

"Was it done intentionally? Was it an accident? You've got a million questions that you'll never have an answer to. Is there anybody else out there like us? How many are out there like us?"

There's anger too

There's more than just wonder. There's also disbelief.

"I can't believe that you put your trust in a hospital, and you go in and have a baby, and they send you home with somebody else," said Avery.

There's also anger. Both men feel the health-care system failed them.

The DNA tests set off powerful emotions, but also triggered a call to lawyers.

Suing for damages

"In the beginning, I didn't even want to talk about it, but when [my] DNA results came back, I called Craig and we went from there," said Hynes.

They claim provincial health authority Eastern Health was negligent by failing to provide accurate identification processes for newborns in its care and failing to discharge newborns into the care of their biological families.

Both Hynes and Avery said a legal settlement won't change what happened to them — or take away the pain — but the hospital should be held accountable for what happened.

"They should be made to be more careful to make sure this doesn't happen again," said Avery. "There could be a lot more people who are in the same situation as us."

The claims by Hynes and Avery haven't been proven in court.

Better to have never known?

What they learned sent shock waves through many generations of both their families.

"It's pretty life altering and it's affected a lot of people. Sometimes I wonder if I should have said anything or [if] I should have just kept it to myself," said Tracey Avery.

She's asked both her husband and Hynes if they wish she'd never said anything.

"The two of them said, 'No, not at all,' because, you know, you've got family out there — you've got to know that, right?"

Christmas times 2

It's complicated, but Hynes and Avery are trying to move forward by focusing on what they've gained.

"I didn't want to go to my family and tell them that I wasn't their brother. My sisters had a very hard job of it. I guess they felt they were losing me, but they didn't lose me; I just gained another family," said Hynes.

This year will be the first Christmas with their newfound families.

"I had a happy childhood, and I had happy teenage years, and growing up everything was good. They're still my family. You know, I got two big families now and, hopefully, one day it will all be one big family," said Avery.

Eastern Health confirmed in an emailed statement that it has received a statement of claim alleging two infants were discharged to the wrong families at the former Come By Chance cottage hospital in 1962.

"Eastern Health empathizes with the individuals and families involved," the statement reads. "We are currently reviewing the statement of claim which is before the courts."

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador