Charbonneau commission: A look back at the explosive testimony and key witnesses

This week Justice France Charbonneau is expected to hand down her final report on allegations of widespread corruption in Quebec's construction industry.

The long-awaited report is the culmination of years of work — the corruption inquiry was first announced in October 2011 by former premier Jean Charest.

The road towards the Charbonneau commission started long before 2011. Charest's decision to call for an inquiry only came after mounting public and political pressure for an investigation, and that was the result of a couple years' worth of media reports on cases of collusion and corruption involving the construction industry, political parties and crime groups like the Mafia.

As the commission draws to a close, here's a look back at the key witnesses and the explosive testimony heard by the corruption inquiry.

Lino Zambito — a former executive of Infrabec Construction, a major contractor for the City of Montreal — delivered some of the most hotly anticipated testimony at the corruption inquiry.

He named names and detailed his involvement in a collusion scheme that included billing city hall for falsified expenses on municipal projects, rigging bids for public works contracts and paying off the Mob. He also explained how a cartel of companies split up contracts in Montreal and Laval.

"The law gave you the right to bid, but if you weren't part of the club, you wouldn't get a contract where you'd make any profit," he told the commission.

Having already been accused of engaging in criminal activities prior to his testimony, Zambito has since pleaded guilty to six charges including fraud and conspiracy.

Zambito also told the commission that entrepreneurs on Laval construction projects were expected to give a "cut" worth 2.5 per cent of the value of each contract to Mayor Gilles Vaillancourt.

Within a month, Vaillancourt — who had served as mayor since 1989 — resigned. The former mayor is currently awaiting trial on 12 charges including conspiracy, fraud, breach of trust and gangsterism. He is also being sued by the City of Laval for $12 million.

Nathalie Normandeau is a former provincial Liberal cabinet minister who has faced a number of questions regarding illegal campaign fundraising.

She's also been accused of accepting lavish gifts from companies.

Star witness Zambito said he gave her tickets to concerts on several occasions and sent her roses, and that he ended up organizing a political fundraising event for Normandeau.

She has also been linked to the scandal involving the awarding of the contract for a Boisbriand water-treatment facility.

Documents revealed last year showed that Normandeau overruled senior bureaucrats when she was municipal affairs minister to award the $11-million contract to engineering firm Roche.

The allegations of her involvement have not been proven in a court of law.

Tony Accurso, who fought his subpoena to appear before the commission all the way to the Supreme Court, has been described as many things: a tycoon, a construction magnate, a successful entrepreneur.

But over the course of the Charbonneau commission, he was also described as an alleged friend of the Mob.

Zambito told the commission that the now-deceased boss of the Montreal Mafia, Vito Rizzuto, once mediated a dispute he had with Accurso over the awarding of a particular contract. Accurso denied ever meeting Rizzuto.

And then there's the boat.

Photos of union bosses and city officials partying on Accurso's luxury yacht, The Touch, may remain among the most iconic images of the commission.

Accurso freely admitted to having close, family-like relationships with high-ranking union leaders, many of whom vacationed in the Caribbean on his boat. But he also denied ever using his connections to secure contracts.

He also told the commission that he had an extensive network of contacts that included some members of the Montreal Mafia. However, on his final day of testimony he downplayed his alleged Mob connections.

"I don't have any link with organized crime," Accurso told the inquiry. "I've never ever paid a cent for any reason whatsoever to Mr. Rizzuto or a member of his entourage, or to an acquaintance of his."

Accurso is awaiting trial on six charges, including fraud, forgery, conspiracy and breach of trust.

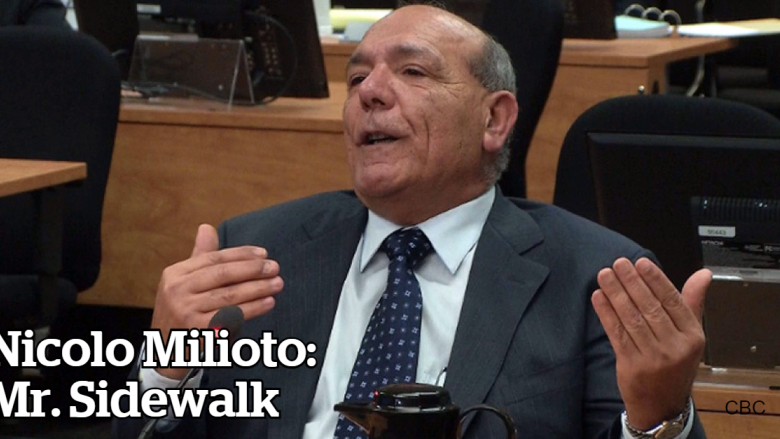

Described by police as the "middleman" between the industry and the Montreal Mob, Nicolo Milioto notably denied even knowing what the Mafia was when he took the witness box in February 2013.

During four days of heated testimony, Milioto — known as "Mr. Sidewalk" for his stranglehold on city sidewalk contracts — denied virtually every allegation against him.

Milioto's alleged links to the Mob made headlines in the fall, when an RCMP officer testified before the commission that he was captured on police surveillance video 236 times at the Consenza Social Club, a once-popular Mafia hangout in Montreal.

He was infamously caught on surveillance video stuffing cash from a construction boss into his socks and handing it to a known associate of Nick Rizzuto Sr., the patriarch of the reputed crime family.

Milioto admitted that he took money from another construction entrepreneur and brought it to the former Don of the Montreal Mob, but he insisted he was merely doing a favour for a friend and didn't ask what the cash was for.

Milioto's company's work with the city jumped between 2006 and 2009, topping out at nearly $22 million in contracts.

A former employee of the FTQ union-federation's construction wing, Ken Pereira, told the commission he stole documents from the union's office that showed its executive director, Jocelyn Dupuis, was running up "astronomical" expenses.

But after he turned to police and former Enquête investigative journalist Alain Gravel, he said it became clear his life was in danger.

He said the federation's top brass tried to buy his silence, offering him $300,000. He also testified he was told to shut up by a highly placed associate of Montreal's Mob, Raynald Desjardins.

Pereira also testified that organized criminals fixed the 2008 election for the union's executive.

He said bikers had been seen circling the polling station. Then a candidate not connected with organized crime suddenly pulled out of the race.

Gilles Cloutier described himself as an election fixer in his Charbonneau commission testimony, admitting to fixing up to 60 turnkey elections in areas around Montreal between 1995 while working for engineering firm Roche.

The firm, he said, then benefited from municipal contracts.

He regaled the inquiry with tales of fixing elections, cooked books, flipping houses and illegal political fundraising.

Then he admitted he had lied about some of it. Cloutier was arrested on Sept. 2 in connection with 15 allegations of perjury related to his Charbonneau Commission testimony.

No charges have been laid.

Bernard Trépanier — the man identified by some construction execs as the lynchpin in a contract-splitting scheme at Montreal city hall — earned his nickname by allegedly charging a three per cent fee to companies he helped win construction contracts.

The former head of fundraising for the now-defunct municipal party Union Montréal told the province's corruption commission that a system of contract-sharing among engineering firms existed before he took up his post with the party in 2004.

They asked for his help, Trépanier testified, insisting that what was in place wasn't a "system of collusion," but rather an agreement in an open market. He said he shared information with the firms about upcoming projects and helped to make sure the work was divided up fairly amongst them.

In July, Quebec's anti-corruption squad UPAC raided Trépanier's home in connection with the water-meter scandal.

The city awarded the $355-million contract to private consortium GÉNIeau in 2007 but cancelled the deal two years later after reports surfaced of alleged embezzlement and other irregularities.

Michel Lalonde is the self-described liaison between Montreal engineering firms and the Union Montréal party.

In his testimony, he told Quebec's corruption inquiry about the details of a kickback scheme that he says directly benefited the former mayor's party for more than six years.

Lalonde, of the engineering firm Génius Conseil (which was bought by Beaudoin Hurens in 2014), testified that he was asked to act as the "spokesperson" for the construction firms in the decision-making process over which firms were to become eligible for lucrative city contracts.

Lalonde testified that he worked with former Union Montréal treasurer Bernard Trépanier to choose contractors from a pool of firms which were in on the bid-rigging and put forward their offers to the municipal selection committee.

According to Lalonde, three per cent of his firm's contracts then went to the municipal party's election fund, in the lead-up to the November 2009 municipal election.

Lalonde estimated that his firm gave between $50,000 and $100,000 a year to the party between 2004 and 2009.

Since Frank Zampino's testimony at the Charbonneau commission, the former chairman of the city's executive committee has had his participation in the awarding of the GÉNIeau water-meter contract scrutinized.

Court documents released at the end of 2014 show that police used his agenda to track Zampino's whereabouts, placing him at meetings with several entrepreneurs in the running for the contract bid.

During the course of the corruption inquiry, his name peppered the testimony of a stream of witnesses from the construction industry.

Many of them pointed to the Zampino as the man pulling the strings in a collusion scheme that allegedly saw large engineering firms paying big donations to the Union Montréal party in exchange for entry into a municipal contract-sharing arrangement.

The longtime right-hand man to former mayor Gérald Tremblay, Zampino left municipal politics in 2008.

He was arrested in 2012 and charged with fraud, conspiracy and breach of trust. Investigators allege Zampino was the mastermind behind a scheme to favour one company in the awarding of a $300 million municipal contract.

In 2014, Zampino's home was searched along with the homes and offices of several other people whose names have come up at the Charbonneau commission, including Tony Accurso.

Former Montreal mayor Gérald Tremblay, who stepped down from his post while pleading his innocence months before his testimony, told the commission he was never informed about a system of public contract collusion.

The first reference of collusion that was brought to his attention, he told the commission, came in the form of a 2009 report by the auditor general.

He also denied knowing anything about off-the-books fundraising by his party Union Montréal, although other witnesses testified funds were solicited in exchange for favourable access to city contracts.

How willfully blind the former mayor was, though, is now being called into question.

Quebec's anti-corruption unit (UPAC) raided his home this past summer with a search warrant based on the testimony of 11 people who met with investigators between 2011 and July 2015. UPAC had "reasonable and probable grounds to believe that Tremblay knew" about the illegal financing scheme of his party Union Montréal, according to the search warrant.

None of the allegations against Tremblay have been tested in court.