The Charter of Rights and Freedoms vs. vaccine mandates — and government inaction on COVID

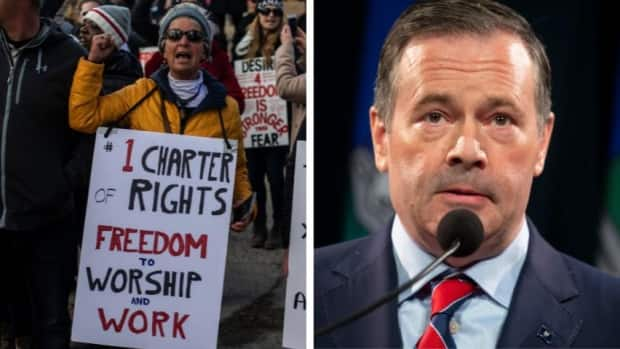

Many who oppose COVID vaccine passports adamantly insist such programs infringe upon rights and freedoms — often citing the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

It has been mentioned again and again, in Alberta and across the country, as protestors opposed to vaccine passports yelled abuse at health-care workers in front of hospitals, marched in the streets by the thousands, likened mandates to the horrors suffered by Jewish victims of the Holocaust, and harassed staff at participating businesses until some temporarily closed.

But they'd likely face tough odds if they tried to use the charter to challenge vaccine passports — except, perhaps, in rare and specific circumstances, some legal experts say.

Meanwhile, governments that delayed passports and stricter health measures to keep from infringing upon our rights may be vulnerable to possible — albeit improbable — challenges that inaction on COVID-19 violated those rights, instead.

Here's a look at how the charter might help or hinder legal arguments for both sides of the debate.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms — heavily promoted by then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau — was eventually entrenched into the Canadian Constitution in 1982, and protects many rights and civil liberties.

But there's a common misunderstanding of how the charter works, says Carissima Mathen, a professor of law at the University of Ottawa who specializes in the Constitution.

The charter does not apply to everything that happens in Canada.

It applies only to governments, their agents and their laws.

"[The charter] is a way to hold the state accountable for laws and decisions that may be oppressive," Mathen said.

This means charter challenges to a vaccine mandate could apply only if that mandate was implemented by the state, and only government employees can bring charter challenges directly against their employers.

In other words, if a business required employees to get vaccinated because it was following a government rule, the employees couldn't challenge the company directly under the charter — they'd have to go after the government for its policy.

But this stipulation has not stopped the charter from being cited, at times indiscriminately, by protestors. And some sections come up more often than others.

Life, liberty and security of the person

The charter's Section 7 has been heavily referenced by some in their challenge against vaccine mandates.

It protects the right to life, liberty and security of the person.

However, it includes a critical, and seemingly overlooked, limitation.

A valid claim under Section 7 can be made only if it can be proven that the life, liberty or security of the person was violated in a way that contravenes principles of fundamental justice, says Jennifer Koshan, a professor in the faculty of law at the University of Calgary.

"If a person was going to try to make a claim that a vaccine passport violated their freedom, violated their liberty, they would have to show that that was done in a way that was arbitrary, or that went too far," Koshan said.

With the charter's application to the state in mind, how would Section 7 fare against vaccine mandates?

Let's look at some examples in Alberta.

Proof of vaccination in Alberta

The UCP government's restrictions exemption program began Sept. 20. It offers non-essential businesses like restaurants a choice: opt in, ask patrons for proof of vaccination, and duck health restrictions — or opt out, and adhere to measures such as capacity limits and curfews.

The City of Calgary, on the other hand, implemented its own vaccine passport bylaw on Sept. 23 that legally requires non-essential businesses to ask patrons for proof of vaccination.

In these instances, patrons of businesses enforcing mandates could argue their liberty is being infringed upon by the government policies under the charter — but it would be unlikely to amount to a violation of the principles of fundamental justice, Koshan says.

If mandates do not require that the employees of participating businesses be vaccinated — such as those under Alberta's restrictions exemption program and Calgary's vaccine passport bylaw — there is nothing for staff to challenge under the charter.

And if a private employer were to independently opt to require its employees to be vaccinated, it would not be an action taken by the state — and so the charter would not apply there, either.

Coercion and occupation

Challenges that would be more viable under the charter could be levied at government employers such as Alberta Health Services and the City of Calgary, which have mandated employees be fully vaccinated by Oct. 31, 2021.

But as with all vaccine mandates in Canada, these employees aren't being forced to get the jab — they are still being presented with a choice.

They can choose to work somewhere else.

"The question would be whether that's still a form of coercion, even if it's indirect," Mathen said.

"You might be able to get over that hurdle and show that the state is putting pressure on you to make a certain kind of decision."

But under Section 7 alone, Mathen says, this would still likely not be enough for vaccine-mandated employees to be successful.

The courts have been very clear that it does not include a right to a specific occupation, she said.

"You'd have to make a broader argument that is unrelated to the mere fact that you want to work in a particular place," Mathen said.

"The one other possible right I would see that as being most implicated by a vaccine mandate could be an equality argument."

Equality rights under the charter

The equality rights protected under the charter's Section 15 emphasize the right to be free of discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

In order to argue that your rights under the charter's equality guarantees have been violated, a person would have to show a link between the mandate and one of these personal characteristics, Mathen said.

"It can't just be you're being treated differently from other people because you don't want to get vaccinated," she said.

However, Alberta's restrictions exemption program and Calgary's bylaw both seem to accommodate potential disability challenges by accepting documentation of a medical exemption for vaccines.

"I also think that raising general concerns about equity would be difficult because, you know, [vaccines are] widely available, they're free," Mathen said.

"The state has made a lot of efforts, I think, to ensure access to the vaccine as much as possible."

But another essential component of the charter would present yet another hurdle to clear.

Even rights and freedoms under Section 15 are not absolute — and are likely to be constrained when pitted against the broader interests of society.

Reasonable limits

The charter's Section 1 states that all of its rights and freedoms are subject to reasonable limits.

Although the charter's purpose is to protect the individual from the majority's wishes in many circumstances, Mathen says this gets analyzed differently when upholding individual charter rights would present a clear risk to public health.

And while people have the right to behave as though COVID isn't a big deal for themselves, Mathen said, they don't have the right to behave as though it isn't a big deal for everyone else.

"In the case of vaccine mandates by state employers, there'd be pretty strong protection for those decisions … given everything we've gone through," Mathen said.

"With all of the evidence we have about the harms of COVID … and the particular challenges posed by [the delta variant], I would think that the balance would probably be on the side of [upholding mandates as] a reasonable limit."

Indeed, Alberta is now well-versed in the harms of COVID and challenges of delta.

The province currently accounts for almost half the active cases in Canada, despite only having about one-tenth of the nation's total population.

And when considering the landscape of COVID in Alberta now — and what led to this point — a different question emerges about the charter and its purpose to hold governments accountable.

The province's COVID inaction

When Alberta dropped virtually all health restrictions on July 1, reported cases of COVID-19 in Alberta soon skyrocketed.

A wave of hospitalizations and delayed surgeries followed. And on Sept. 23, Alberta Health Services CEO Verna Yiu said the reason ICU beds have remained available at all is because each day enough are vacated by the dead.

In fact, it was reported on Sept. 28 that Albertans are dying from COVID-19 at more than three times the average Canadian rate.

As Dr. Deena Hinshaw, Alberta's chief medical officer of health, admitted in a Zoom conference with Primary Care Network Physicians on Sept. 13, the province is in crisis — and it's because the provincial government did not maintain health restrictions that could have kept its citizens safe.

WATCH | Number of ICU patients the highest in the province's history:

According to the federal government, under the charter's Section 7, the right to life can be engaged when state action imposes death or an increased risk of death, either directly or indirectly.

Security of the person, meanwhile, can be engaged when state action has the likely effect of seriously impairing a person's physical health.

Could those who became seriously ill during COVID's unfettered fourth wave — or whose surgeries were delayed, or whose family members died — challenge the state under Section 7?

"That's a very interesting question, and it really gets to the essence of how we perceive our rights and freedoms in Canadian society," Koshan said.

Vriend vs. Alberta

It deviates, Koshan says, from the traditional view that rights and freedoms are there to protect us from government action that could infringe on them.

But sometimes, government inaction can violate rights and freedoms. An example happened in Alberta during the 1990s, when sexual orientation was not protected in human rights legislation.

Back then, if someone was discriminated against on the basis of their sexual orientation — say, fired from their job— they were not able to bring forward a human rights complaint, Koshan says.

WATCH | April 2, 1998: Discrimination based on sexual orientation ruled illegal:

"There was a case that went to the Supreme Court of Canada called Vriend in 1998, which decided that in the circumstances of that case, government inaction did amount to a breach of the equality rights of the charter," Koshan said.

The argument this time, Koshan said, could be that the government's inaction resulted in deprivations of security of the person and, in some cases, their right to life.

So, let's lastly review some of the timeline of the government's response to Alberta's fourth wave.

Section 7 and a life-and-death crisis

The province lifted most public health restrictions on July 1, after more than 70 per cent of eligible Albertans received their first dose of vaccine.

Some doctors cautioned at the time that reopening was risky, and the plan had been drafted before the arrival of the highly transmissible delta variant.

By the end of July, health and infectious disease experts began raising the alarm that COVID was already spreading faster in Alberta than at the peak of its third wave.

Hinshaw told the media on Sept. 15 that the government began to realize in early August that its reopening plan — which hinged on the decoupling of COVID cases and hospitalizations — wasn't working.

Yet that realization was followed by a weeks-long disappearance from public pandemic updates by Premier Jason Kenney, then health minister Tyler Shandro and Hinshaw until a collective COVID announcement on Sept. 3 — over a week after new daily cases climbed past 1,000.

Resisting mounting pressure to implement a vaccine passport system, Kenney instead offered unvaccinated Albertans a $100 incentive to get the shot, and reintroduced some mandatory masking restrictions and a liquor curfew.

Active COVID-19 cases in Alberta

Amid a raging fourth wave and looming ICU bed shortages by Sept. 15, Kenney declared a state of public health emergency and announced the restrictions exemption program.

Both the Canadian Medical Association and the Alberta Medical Association issued calls on Sept. 29 for short lockdowns to protect the province's crumbling health-care system.

Though members of the Canadian Armed Forces and Canadian Red Cross will be sent to assist Alberta's hospitals, the government is not currently considering additional health measures, Kenney said Sept. 30.

The Canadian Press's Dean Bennett asked why Kenney still feels he has the luxury of time and isn't giving doctors the lockdown they're asking for.

"The crisis that we are dealing with comes overwhelmingly from the unvaccinated population," Kenney said.

"We need to address that, which is what the current measures seek to do. We will take additional action if it is necessary."

Drawing a link

Like claims against vaccine mandates, pursuing a charter claim against the province would have its challenges.

For one thing, courts have historically been more reluctant to find charter breaches because governments have done too little, rather than too much, Koshan says.

For another, it would have to be proven that the rights protected under Section 7 were violated in a way that contravenes principles of fundamental justice.

"I find it an intriguing argument, but I'm doubtful that the courts would go there," Mathen said.

And a third challenge would likely be an evidentiary one, Koshan said.

"That comes down to a question of whether you would have enough scientific evidence, as well as causal evidence, to draw a link between the inaction and the harms that were ultimately done," she said.

And if that link could be drawn?

"There's certainly some argument to be made," Koshan said, "if governments … aren't taking proper actions to protect their populations."