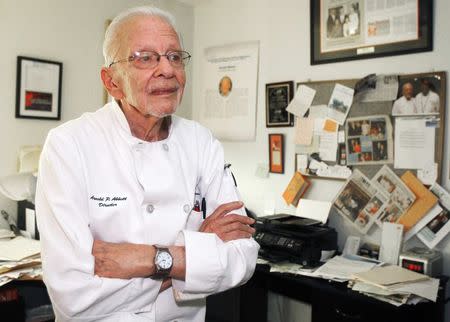

Chef, 90, faces jail, fines for feeding the homeless

By Zachary Fagenson MIAMI (Reuters) - For decades, 90-year-old Arnold Abbott has hauled pans filled with roast chicken and cheese-covered potatoes onto a south Florida beach park to feed hundreds of homeless people. For his good deeds, Abbott finds himself facing up to two months in jail and hundreds of dollars in fines after new laws that restrict public feeding of the homeless went into effect in Fort Lauderdale earlier this year. “I’ve been fighting for the underdog all my life, so this is nothing new,” Abbott said. He was first cited last Sunday, along with two clergymen and a volunteer from his nonprofit, Love Thy Neighbor. On Wednesday, several police cars waited for Abbott at a downtown Fort Lauderdale park, and officers pulled aside the frail man, clad in a white chef’s coat, soon after the first plates were ready to be served. “The ordinance does not prohibit feeding the homeless; it regulates the activity in order to ensure it is carried out in an appropriate, organized, clean and healthy manner,” Fort Lauderdale Mayor John P. Seiler said in a statement. Abbott moved to Florida from Massachusetts in 1970 and was a civil rights activist and wholesale jewelry salesman. He and his wife first began feeding the homeless on their own in 1979. He started the foundation and feeding full time in 1991 after his wife died, in a tribute to her memory. The dispute highlights a debate between two schools of homeless rights activists: Those who argue that banning public feeding criminalizes the homeless, and others who say feeding and panhandling helps keep them on the street. Since January 2013, 21 cities across the country have passed laws restricting public feedings and 10 more have similar rules under consideration, according to an October report from the National Coalition to the Homeless. Nationwide, at least 57 cities have limited or banned public feeding. "One of the reasons these kinds of ordinances are being embraced is that this is what cities can do without spending money,” said Jerry Jones, the coalition’s executive director. A widely agreed-upon solution - giving the longtime homeless beds as they work their way into treatment programs - is too costly for many municipalities that struggle with homelessness. But advocates for the homeless say that ignores the costs of not addressing the issue in a compassionate way. “What’s the cost if somebody presents themselves five times annually to an emergency room?” asked Ron Book, a high-profile Florida lobbyist who chairs Miami-Dade County’s Homeless Trust with a tax-backed, $55 million budget. (Editing by David Adams; Editing by Bernadette Baum)