This Chicanx Artist Makes Political Art For the Instagram Age

This profile is part of our series “Quiénes Somos,” which focuses on nine amazing and original creators in the Latinx community. You can read more by visiting our Latinx Heritage Month homepage.

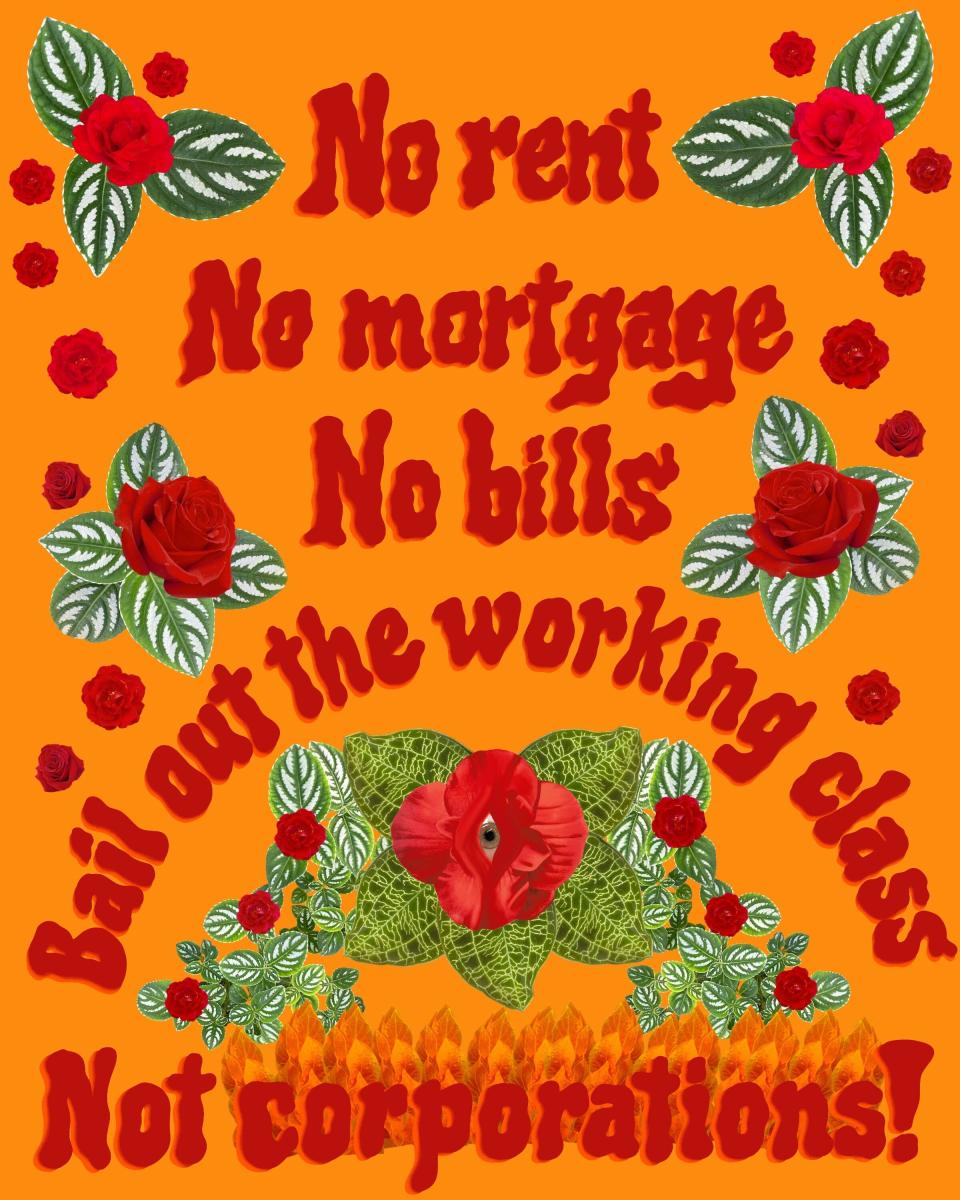

For many folks, their first introduction to the work of Bay-Area based Chicanx artist Ruby Marquez, who also goes by Broobs, came after the murder of Ahmaud Arbery. Marquez’s graphic of Arbery, framed by plants and flowers that the artist photographed themself, was shared widely across social media.

During the Black Lives Matter protests this past summer, similar images of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were also a part of the conversation. These images ― like much of Marquez’s work ― were political art for the Instagram-age ― colorful photo collages made to be shared across feeds, grids and timelines during a moment of national racial reckoning. This wasn’t art for art’s sake. This was art as a call to action; each piece paired with an urgent plea for justice.

HuffPost talked to Marquez during Latinx Heritage Month to learn more about their work and background.

Tell me about your background. Where are you from?

I grew up in Montebello, California. I think people consider it East LA. I’m not too sure. Some people do, some people don’t. I lived there my entire life.

Did you always want to be an artist?

My dad always wanted me to be a firefighter [laughs]. So when I started going to community college, that was my initial focus. But during my second year, I was like, “I have some electives to fulfill, why don’t I do something for me.” So the first class I took was a digital photography class. My work got into the art show. After that, I was like, “Oh, maybe this is something I actually like to do.”

Has your family been supportive of your career choice?

Well, I don’t have a relationship with my dad mostly because when I came out as queer, he didn’t want to be a part of my life anymore. But my mom is really supportive. She’s really happy with how my career is turning out. I think it was when I got my first gig doing work with Netflix, she realized, “Oh shit, you’re actually doing something.”

I can’t help but notice the influence of Catholic iconography in your work.

Growing up it was really my mom and my grandma who took care of me. My grandma was the lady at church that everybody knew because she was always there. She was a catechism teacher. She was also involved in everything the church did. And because she was always taking care of me, I spent a lot of time at church too.

One of my earliest memories is getting dropped off at my grandma’s house in the morning before school. She had blackout curtains, but there was always one crack of light that would come in. And that light would always shine on this picture she had of Jesus with thorns and blood running down his face. That’s a really vivid memory in my mind because it always scared the crap out of me.

Marquez’s work often pairs text with botanical imagery they photograph themselves.

COURTESY RUBY MARQUEZ AKA BROOBS

Your work often incorporates floral and botanical imagery. What draws you to these elements?

My love for botanical stuff is from my mom. She taught me how to love and care for plants. My attraction to using them in my work is that nature already has such a heavy design element to it. The way plants and flowers grow compliments art in a very natural way.

All the floral images are photographs I take myself. When the weather is nice, I’ll go for walks and take photographs of leaves and flowers that I see on the streets. Or before lockdown, I had an annual pass to the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers. I would go there and photograph things.

Most of the plants and flowers are native to California. People often assume that I have a library of flowers that aren’t mine. So they’re like, “Can you use flowers from Central America?” I’m like, “No. I’ve never been there, but you can fly me there if you’d like.”

I know a lot of artists, especially on social media, watermark their work. You don’t watermark your pieces. Why not?

Because I don’t feel like my art is about me. I feel like it’s for the greater good.

I have a lot of followers that are constantly tagging me [when my work is shared] and being like, “Hey, tag the artist.” But it’s like, I don’t really need the praise or anything of that sort. That’s not what the message is supposed to be about.

Your work often deals explicitly with the histories of marginalized peoples ― Black history, queer history, LatinX history. What role does history play in your work?

Growing up in LA, we were taught history, but it was just so watered down. So one of the first projects I did was a Pride project in 2016 that dealt with queer icons through history. I was upset at the way pride had become this sort of celebration of rainbow capitalism. It felt like nobody really knew what history we were celebrating anymore. But I also realized that I didn’t really know queer history either. So I challenged myself to research history, make collages, and put what I discovered into the world.

Marquez’s photo collages of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were shared widely during the Black Lives Matters protests this summer.

COURTESY RUBY MARQUEZ AKA BROOBS

Your pieces of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor were shared widely on Instagram during the Black Lives Matter protests this past summer. I’m curious to know what role you think social media plays in your art?

Honestly, that’s something I’m still trying to figure out. When I’m making a piece, it’s not because I want it to go viral. It’s more like, these are stories that need to be talked about. These are conversations that we need to start having with ― not only one another ― but our siblings, our families.

I hope that my art helps talk about racism in a sense, by showing the images of these people and then talking about their stories. In some ways, my art can kind of disarm people. It never questions whether these lives were sacred. A lot of Catholic art was like that. About not questioning the art itself, but rather accepting it for what it is.

Do you feel that in some ways your art does that, too?

I hope that it does. I don’t know if it does for sure. I’m sure it hits everyone differently. But that’s the beauty of art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.