Christiane Ritter: Why this forgotten feminist nature writer deserves to be celebrated

In 1933, an Austrian housewife called Christiane Ritter travelled with her hunter-trapper husband to spend the winter in the icy wilderness of Svalbard. Five years later, she published an extraordinary book about how “the peacefulness of nature” affected her. It’s a radical, feminist text that speaks to the disconnection from the rest of nature we are experiencing at unprecedented levels today. It’s hard to believe it was written over 80 years ago.

I read the book before and during a research trip to Svalbard for my book Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild. It’s a cult classic in some circles, but it deserves to be more widely known. It proved that women could thrive, let alone survive, in a tough environment like the Arctic tundra.

A Woman in the Polar Night is remarkable for a few reasons. First, accounts written by women about hanging out in the wilderness in the early 20th century are hardly two a penny. At the time, few women were published, let alone female writers of the landscape. Nature writing by women existed – Susan Fenimore Cooper, Dorothy Wordsworth, Phillis Wheatley and Emily Brontë, for example – but it wasn’t until the 20th century that Nan Shepherd, Rachel Carson and Annie Dillard paved the way for the growing number today.

I took a trip to the Arctic Circle because I wanted to visit the Global Seed Vault, where seeds are stored in case of disasters from nuclear war to climate change (a symbol of our disconnection from the natural world if ever there was one) and I was interested in how the vast, wild landscape might affect my emotions. Would I achieve serenity? A deeper wisdom that I had lost? Was two days enough time to quiet anxiety and refresh the soul?

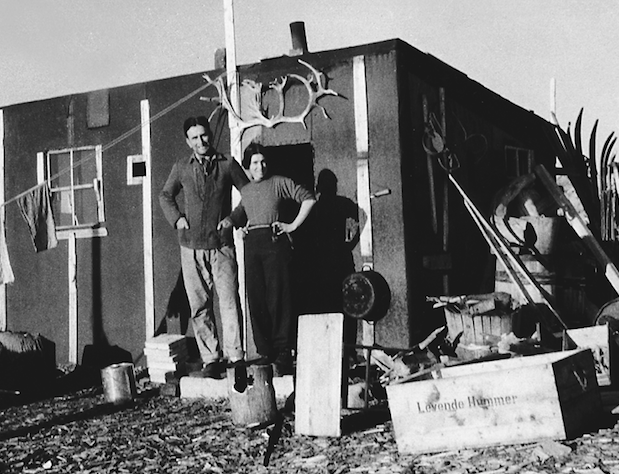

It took 24 hours of travel through misty gloom for Ritter and her husband, Herman, to arrive at Spitsbergen. The airport had yet to be built. To give you an idea of how uninhabitable this place was, the coasts were called Anxiety Hook, Distress Hook, Misery Bay and Bay of Grief. It was hardly a tourist destination.

At first, Ritter is horrified at the prospect of spending months in a small hut on a vast tundra. The mountains are “frightening in their vast bleakness”. When the polar darkness falls, the sounds of blocks of ice crashing against one another is deafening. She begins to understand why the coasts were given their names.

But when the mist settles on the “milky white” snow and the mountains that “glow pink” she feels “light as a feather”. She’s unusually open in revealing her inner, emotional life and surprisingly psychoanalytical for the time. Why have I been so shaken by the peacefulness of nature, she asks, turning her anxieties and fears over in her hands like a snow globe. It brings the reader into the “small, bare, bleak box” with her, grossing out over the hunter with peas and lentils stuck in his beard.

As the story continues, her enchantment grows. She is bewitched by the beauty and the holy quiet. She interprets the northern lights as a serene light that “has in it something that yearns toward the earth, something sheltering, consoling, promising, and yet utterly mute in its remoteness”. She records that the indigenous population believed they could see the spirits of their loved ones in its “drifting veils”. Under the radiance, her spirit is calm and clear.

Ritter wonders if people in the future will go to the Arctic to find the truth, just as Biblical-era men withdrew to the desert. She finds she has no need for diversions such as music. “Our ears are light, our minds are in a permanent state of elevation. Nature seems to contain everything that man needs for his equilibrium.”

Often poetic, her description of a full moon is almost psychedelic. “It is as though we were dissolving in moonlight, as though the moonlight was eating us up... one’s entire consciousness is penetrated by the brightness; it is as though we were being drawn into the moon itself.”

The untouched landscape is magnificent but also frightening. Later, when she is alone for some time in the hut, she understands the “terror of nothingness” that must have been responsible for the death of hundreds of men. She recounts a haunting story about a hunter’s wife who was left in a hut alone over a freezing winter. The hunter could not return until the drift ice melted. During that time, the woman gave birth to a baby, alone, who was living and healthy. But the “long night and the fears she had endured” left the mother “deranged in mind”.

When the sun returns, Ritter and her husband are in the “highest of spirits”. They celebrate with a whole spoonful of honey with their coffee and cold seal.

The flight I took to Svalbard from Oslo was surprisingly full. It was an old plane, with evidence of ash trays glued to the walls. As we passed through the Arctic Circle, I saw dream-like swathes of pastel-coloured aurora in the sky outside: chalky pink, light green, pale blue, soft orange. As we neared the port of Svalbard, ships nestled together like glowworms in the pitch-black ocean.

Naively, I’d imagined I might be able to walk away from the town and into the wilder areas but I didn’t know how to use a gun (a prerequisite for leaving the settlement; polar bears outnumber people). My experience was in no way similar to Ritter’s but I did find my anxiety was quietened when I looked at the vast, cream-gold mountains. Perhaps it was their permanence, their immovability and immutability. They are always and forever, an existential Valium.

In 2017, shortly after I visited, the unimaginable happened and the Seed Vault flooded due to melting permafrost. Longyearbyen, the settlement in Svalbard, is now the fastest-warming town on the planet. The sea in the harbour, locals told me, stopped freezing over about 10 years ago. Even in the two years since I visited, the world feels so much more precarious. Svalbard is currently on the front line of the climate crisis.

I think there is an important truth in Ritter’s book. While researching for Losing Eden, the more I saw how strong and varied the evidence is for a connection between nature and mental health, the more I became convinced that we are losing something psychologically important as we continue to disconnect further from the rest of nature. Ritter, writing way before the climate crisis, global species decline and habitat destruction, was sounding an alarm. “I realise that civilisation is suffering from a severe vitamin deficiency because it cannot draw its strength directly from nature,” she wrote. “Humanity has lost itself in the unnatural and in speculation.”

Flying back home, over landscape that would be impossible for humans to reach, over peaks upon peaks of meringue glaciers, spills of ice, I felt calmed by that “peacefulness of nature” Ritter wrote about. The seas were swirled with frost, as if by a painter herself, by icy currents, a cold sea fizzing with marine animals, krill, crustaceans, amphipods.

While the quantitative evidence for how nature affects our minds has grown over the last few decades, humans have always expressed the power of the wilds to offer mental succour. But few have written about it so generously and beautifully as Christiane Ritter.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones is published by Allen Lane on 27 February