Chronic pain patients suffering because some doctors too fearful to prescribe opioids

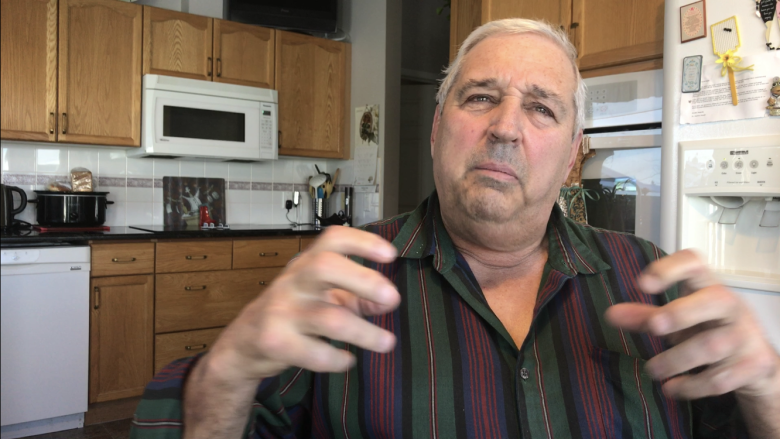

Larry Metz rates his flu-like aches and pains a 12 out of 10 today, but some days he says it's as high 14, now that his opioid pain medication isn't strong enough to numb the pain.

So the fibromyalgia sufferer and diabetic says maybe it's the pain talking. Or maybe it's his tell-it-like-it-is attitude he's picked up over his many years working in a gravel pit, driving a grader and building roads.

Either way he's mad at Alberta's College of Physicians and Surgeons because he believes they're the reason why his doctor won't boost his pain medication.

"Grow up. Wake up. Take off your ties and put on some blue jeans and go out and get in the mix and middle of the people that are going through this stuff."

"It's easy to sit up in your high towers," adds Metz, 68. "Understand where they're coming from, talk to them."

Ever since the college implemented its opioid prescribing guidelines last spring, some chronic pain sufferers say they've seen their pain medications reduced, or tapered completely, and definitely not increased as requested.

The latter has been Metz's experience.

"It would numb the pain so I could walk around Walmart," said Metz, who's prescribed 20 mg of Oxyneo, a time-release opioid, twice a day.

"I want to go fish, I want to go [wrestle] with my grandkids, give them a hard time."

A spokesperson for the Alberta Medical Association says this has not gone unnoticed in the medical community.

"We're not debating that, many of us have heard that, and it's really quite a pity," said Dr. Marc Klasa, the head of the AMA's chronic pain section.

Klasa attributes it to unneccessary fear and confusion among physicians.

Not rules, just guidelines

The college says the new guidelines were meant to help address the opioid crisis by reducing the amount of opioid painkillers being prescribed.

And it says it's worked.

The college says that between September 2016 and September 2017, the number of Albertans prescribed the five main opioid painkillers dropped by seven per cent — that's 9,000 fewer people prescribed opioids in a given month (mainly codeine).

But it also realizes not all patients will be able to taper off their medications.

"We're not just saying these are the rules, follow them. I think that needs to be made very clear," said Kelly Eby, director of communications & government relations for the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta.

"It is very clearly stated in the standard that this is a recommended dose for most patients and there will be exceptions."

Yet despite the college's best efforts, Eby says the message is not getting out there.

Fear factor

But patients, like Metz, say their doctors flat out tell them they're scared to maintain or boost opioid pain meds because they believe the college is breathing down their necks.

"So I guess they're told by the big shots in Ottawa or wherever it comes from, not to do it — and that's all there is to it," said Metz.

The Chronic Pain Association of Canada says it's hearing similar stories from across the country.

Executive director Barry Ulmer says he knows of an 83-year-old woman with severe arthritis whose pain was well-controlled for years by opiates but is now living her final years in sheer agony without effective pain medication.

"And nobody seems to want to accept the view from the people who are suffering," said Ulmer.

Dr. Gaylord Wardell sees chronic pain patients in Medicine Hat and says the college documents every one of his patients and highlights those who exceed or in some other way run afoul of its guidelines.

He says there is no actual implication of consequence but most lawyers would agree there is an implied threat.

"Put yourself in the place of a family doc with only a few patients on opioids. If the CPSA [the College of Physicians and Surgeons] were to sanction them, their livelihood could be jeopardized by a few patients. The incentive to get rid of these patients, although the CPSA says no to do so, is quite high," says Wardell.

Source of confusion

Klasa says the problem is some doctors still think the recommended doses are absolutes and they can't be adjusted to fit the patient.

Klasa says part of the confusion was with the way the guidelines were released at the national level, which Alberta's college bases its own on.

Initially, it put out a draft that provided only key points, which included the recommended doses.

Then weeks later it released a longer form that provided more context.

But he says not all doctors bothered to read the more fulsome version.

"And in the approach that was taken, with not getting this data out in time and sometimes maybe coming across as a wee bit harsh in terms of phraseology by some of the colleges of physicians and surgeons, unfortunately a lot of patients have been kind of harmed by this."

The college says it's heard from a lot of patients since who are concerned because their doctor will no longer prescribe their opioid medication. In those cases, it intervenes to try to help.

"And we've also worked with a lot of patients who don't understand what we are trying to accomplish, and we're working with them and their physician to make sure they're getting appropriate care and appropriate prescribing," said Eby.

In the meantime, Metz says he worries his doctor may one day force him off his medication entirely.

"It's not the withdrawals I'm worried about, it's the pain. I tried it for two days and just about lost it, it was unbelievable. I can see why people commit suicide, I really can."

Metz says he's tried all sorts of therapies before arriving at the point where he's relying on opioids to get him through his day.

He says he'd rather not take this type of drug, but Metz says nobody seems to have any other solutions for easing his chronic pain.