Column: Your future healthcare hangs on the presidential election

On the one hand, expansion of health coverage to millions more Americans and preservation of the federal consumer protections for health insurance that customers enacted a decade ago.

On the other, more obstacles to healthcare and continued withdrawal of the federal government from oversight of the healthcare system.

Those are nutshell descriptions of the approach to healthcare reform touted by the Biden and Trump presidential campaigns.

There may be no more important issue for voters to ponder in the election. Healthcare has ranked high among the topics of interest for voters for years.

If you looked at the way the Trump administration thinks about everything, this is how they think about COVID too. The federal government has no responsibility, there is no sense in working with international partners because it's 'America first,' we're not going to coordinate with the states.

Sherry Glied, health economist

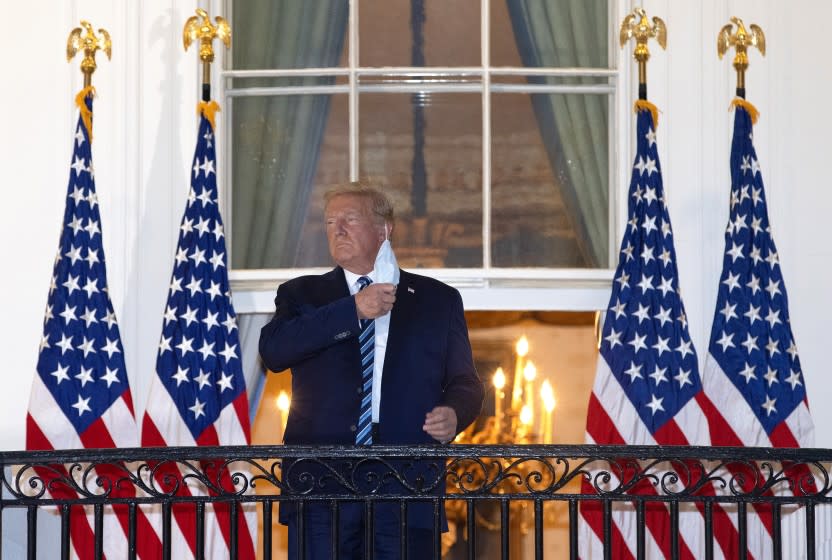

This year, attention on the issue is heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has sickened more than 8 million Americans and killed about 220,000, cratered the U.S. economy and opened deep rifts in the country's social fabric.

Direct comparison between the Biden and Trump platforms is almost impossible — just as it is impossible to directly juxtapose their economic programs — because Biden has produced detailed proposals bristling with numbers and legislative options, while Trump has offered vague promises devoid of specifics.

But neither has Biden proposed a comprehensive measure on the scale of the "Medicare for all" plan offered by Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren during their campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Rather, Biden would build on the Affordable Care Act, enacted in 2010 during the Obama-Biden administration, by expanding its tax subsidies and adding a "public option," which would offer publicly funded coverage to low-income residents of states that haven't expanded Medicaid under the ACA, and to employed persons who can't afford their employer-sponsored coverage.

The most pressing imperative for a Biden administration would be heading off the challenge to the ACA's constitutionality due to be heard by the Supreme Court on Nov. 10, one week after election day.

The case, brought by Texas and several other red states, is based on the premise that when Congress reduced the ACA's individual mandate penalty to zero as part of the GOP tax cut act in 2017, that action rendered the entire law unconstitutional. Most legal experts consider the argument absurd, but they're also amazed that the case has reached the high court.

The Trump administration supported the plaintiff states by refusing to defend the law in court. Biden could restore the government as leader of the law's courtroom defense. By the time he took office, oral arguments would have been completed, but the court might still be open to accepting briefs from the parties.

With the support of a Democratic Congress, Biden could render the lawsuit moot either by restoring an individual mandate penalty or amending the law to make explicit that its provisions are "severable" — that is, the fate of one provision doesn't effect the validity of the rest of the law.

The easiest reform steps Biden could take upon taking office simply involve rolling back Trump's attack on the Affordable Care Act, which has been implemented chiefly through executive orders and regulatory initiatives (some of which have been blocked in federal court).

Among them have been efforts to circumvent the ACA's consumer protections, including protections of those with preexisting medical conditions, by endorsing the sale of junk insurance plans that lack those provisions. The administration has also approved work requirements for Medicaid enrollees, which has resulted in thousands of enrollees losing their coverage.

In the latest such case, the administration on Thursday approved a partial expansion of Medicaid by Georgia.

The Georgia program requires enrollees to spend at least 80 hours a month on the job, or hunting or training for a job, requires up-front payment of nominal premiums, and penalizes enrollees who go to the emergency room for a condition later judged to be "non-emergent." That's a cost-saving provision that even the private insurers that devised it have begun to doubt.

A Biden administration could halt this activity by the close of business Jan. 20.

Other changes would require congressional assent. Biden has proposed eliminating the cutoff of premium subsidies for households with income higher than 400% of the federal poverty line ($104,800 for a family of four), replacing it with a rule that no family would have to pay more than 8.5% of its income for a benchmark plan on the individual market.

He also would change the benchmark plan from a silver plan, as it is today, to a gold plan, which covers a greater share of healthcare costs.

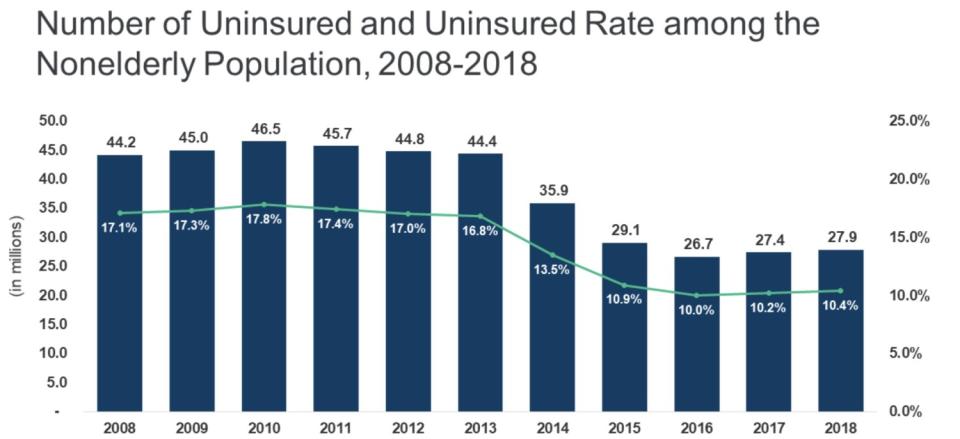

The Biden campaign estimates that those changes and others would raise the share of Americans with access to insurance to 97% from the 92% level reached during the Obama administration, when fewer than 27 million were uninsured. Under Trump, that figure increased by about 1.8 million through mid-2019. Biden says his plan would reduce the legion of uninsured to about 10 million.

Biden's healthcare platform goes beyond passing legislation to "close the remaining gaps left by the ACA," as Sherry Glied, a health economist who is dean of the NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, observed in an analysis of Biden's healthcare proposals published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Biden also would lower the Medicare eligibility age to 60 from 65, a modest expansion that wouldn't require a fundamental change in the program's structure.

He would scrap Trump's "America first" approach to combating COVID-19; as he wrote in a USA Today op-ed in January cited by Glied: "The United States must step forward to lead these efforts, because no other nation has the resources, the reach or the relationships to marshal an effective international response."

Biden and Trump share some stated goals in healthcare reform. Both advocate reducing prescription prices, lowering premiums and ending "surprise billing." Where they differ is in offering specific proposals likely to effect those goals. Although Trump has been in office for nearly four full years, he hasn't achieved any of them.

"It is interesting that there is an alignment on objectives between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party on many of these things," Glied told me. "But there is no alignment on how you get there, since the Republicans think that all the suggestions the Democrats have made are terrible, and yet we don't know how the Republicans want to get there."

Complicating the GOP stance is its predilection for taking the federal government out of healthcare policy and turning it over to the states. As Wharton economist Mark Pauly noted in a companion analysis of Trump's healthcare policies appearing next to Glied's in the New England Journal of Medicine, Republican orthodoxy calls for block-granting funding for Medicaid and the individual health plan exchanges to the states.

Block grants are a notoriously inflexible approach to healthcare funding and are likely to shrink over time in relation to spending needs. In more general terms, Pauly writes: "The overall strategy would be to accept that no uniform Republican plan can (or even should) work at the federal level, nor is it politically feasible, so perhaps the states can do better."

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed the healthcare policy differences between Biden and Trump in sharp relief.

"If you looked at the way the Trump administration thinks about everything," Glied says, "this is how they think about COVID too. The federal government has no responsibility, there is no sense in working with international partners because it's 'America first,' we're not going to coordinate with the states because that's not the role of the federal government, we're going to trumpet the wackiest ideas.

"It's not as though the Trump administration's behavior with respect to COVID is a failure of the administration," Glied adds. "It's actually what the Trump administration has said you should do. The outcomes are what you get if you do that."

By contrast, Biden has called for a domestic and international coordinated response, including "wide availability of free testing; the elimination of all cost barriers to preventive care and treatment for COVID-19; the development of a vaccine; and the full deployment and operation of necessary supplies, personnel and facilities."

He also promises to rebuild the nation's healthcare infrastructure to create "a permanent, professional, sufficiently resourced public health and first responder system ... to ensure greater sustained preparedness for future pandemics."

To put it succinctly: On one side, hands-on; on the other, hands-off.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.