Column: U.S. individualism isn't rugged, it's toxic — and it's killing us

The pandemic has been one long lesson in human adaptability. (Zoom theater anyone?) It has also been a revealer of ugly truths.

In the United States, COVID-19 has put front and center a host of economic and racial inequities. It has also shown the ways in which our sense of the collective has frayed.

The summer has seen a cinematic array of meltdowns in supermarkets and restaurants across the country, all inspired by the simple request to wear a mask. A customer inside a North Hollywood Trader Joe's threw down her basket and blasted frontline staff with obscenities. A woman at a New York City bagel shop stalked up on another customer and deliberately coughed in her face.

And it has only escalated from there. In May, a guard at a Family Dollar in Flint, Mich., was shot and killed after telling a customer that her child needed to wear a mask in the store. During that same period, gangs of armed paramilitaries (calling them "militias" is too romantic) showed up at the Michigan State Capitol to protest stay-at-home orders and mask mandates — at one point, brandishing semiautomatic weapons inside government chambers.

Much of it is fueled by the belief that these measures represent an undue restriction on individual freedom. Former San Francisco Giants slugger Aubrey Huff, responding to "soy-boy professors and the blue check mark crazy cat ladies" "guilt shaming" him for declaring mask enforcement "unconstitutional" said in a Twitter video: Just because others may be susceptible to the disease, "doesn't mean the whole world has to shut down." He added that he would "rather die from coronavirus" than wear "a damn mask."

Never mind that if he does die, he'll likely take others with him, since communicable diseases don't just strike individuals. "The point is that masks do not just protect the wearer, they protect others," stated a Scientific American dispatch from May.

We live in a culture of rugged individualism run amok. Call it toxic individualism. Because in the case of this pandemic, it is literally toxic.

Example-in-chief: the Trump White House, where masks for long stretches of the pandemic have been a rarity, and which may have been the source of at least one super spreader event in October (Rose Garden virus-gate), after which the president himself was hospitalized with COVID-19. When he returned to the White House, he proceeded to rip off his mask, action movie-style.

Less than a week before the election, Vice President Mike Pence's team is taking its turn at the virus wheel as the infection blooms among his staff.

According to the continuously updated figures published by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, as of Wednesday, the United States is among the top 14 countries in the world when it comes to case fatalities from the novel coronavirus, and we are among the top five nations in the world when it comes to per capita deaths.

The focus on individual rights over the greater good is one for which we are paying with our health and our lives.

How did we get here? (Besides all the conspiracy videos on YouTube.) The culture of toxic individualism has deep roots.

A good piece of it is tied to the cultural legacy of manifest destiny and the settlement of the West: the myth of the up-by-the-bootstraps pioneer who helped tame the uninhabited West in the name of the United States.

Never mind that the land was already inhabited by Indigenous peoples. And never mind, as historian Greg Grandin points out in his book "The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America," that the nation building was not the work of rugged individuals working alone but a lot of people working in tandem, with the regular support of the U.S. military and the U.S. Treasury — for what was, to put it mildly, a government handout on an epic scale. ("What we think of as the West, since its inception, has been the domain of large-scale power, of highly capitalized speculators, businesses, railroads, agricultural, and mining," he writes.)

Even so, the mythos of individualism has infused both our culture and our politics.

Herbert Hoover hammered the idea into the popular consciousness by popularizing (possibly coining) the phrase "rugged individualism" in a 1928 campaign speech — in which he described a choice between "rugged individualism and a European philosophy of ... paternalism and state socialism." It was an idea that continued to be echoed decades later by presidents such as Ronald Reagan, who once quipped at a 1986 news conference that "the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: 'I'm from the government, and I'm here to help.'"

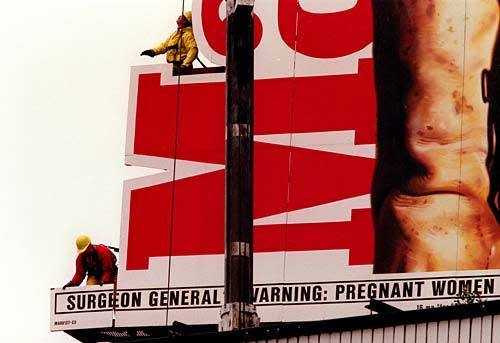

In culture, rugged individualism frequently materializes in the form of the solo cowboy: "The Lone Ranger" popularized by ’30s-era radio, the westerns of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, and the strapping Marlboro Man of cigarette advertising campaigns — a figure that the Economist once described as epitomizing "resilience, self-sufficiency, independence and free enterprise."

Rugged individualism manifests as the solitary, sharp-tongued justice seekers of the 20th century — the early noir detectives, such as Carroll John Daly's tough guy, Race Williams, and the self-absorbed Batman of comics and film. They are archetypes that, as literary scholar Susanna Lee, author of "Detectives in the Shadows: A Hard-Boiled History," noted in a recent essay, may make for great entertainment, but don't offer great role models in a pandemic, when "a fully rounded human and worker among workers — able to tolerate discomfort and put others first" is what we need.

Instead, we have the exact opposite. Trump has shown zero empathy for the more than 226,000 Americans who have succumbed to the disease. At his rallies recently, he complains that all CNN does is talk about "COVID, COVID, COVID."

If Americans had once consumed the myth of the rugged individual, it appears the myth is now consuming us. Individualism is toxic.

In some corners of culture, there has been growing pushback on the idea — a move away from the idea of the "lone genius" and a move toward recognizing the more collective ways in which humans work.

In a 2018 essay in Curbed, architecture critic Alexandra Lange called for an end to the architect profile, noting that, in architecture, focusing a story on one person (almost always a man) maintains the "fiction" that one person "does it all." It was a sentiment echoed recently in a story by New York Times food critic Tejal Rao, who wrote that a focus on star chefs erases the contributions of everyone else in a kitchen. In these highly collaborative fields, to center the story on a single individual is to perpetuate fiction.

For many artists, working collaboratively isn't new. But recent years have seen a greater intention around notions of collective creation.

Early this year, the experimental opera company the Industry staged the critically acclaimed "Sweet Land," an opera that picked apart the tropes of Western expansion and rugged individualism. And it did so not just in content, but in the way that it was made.

Instead of a top-down director system, with its clear pecking order, "Sweet Land" was directed by two people: Industry founder Yuval Sharon and multimedia artist Cannupa Hanska Luger. They worked collaboratively with the opera's composers (there were two), librettists (same), performers and scenic designers to create the work.

"I'm very excited about the notion of shifting attention away from the individual to the collective," says Sharon. "To me, opera is already inherently collaborative, but it pretends that it isn't."

Luger notes that collective work also creates a shared sense of reality.

"We filter our world — with or without the internet — from our perspective," he says. "But when you incorporate a collective consensus, then you are working with more filters. The advantage is that you don't have to live in a vacuum and there is room for a better and more whole conception of your reality. You have other people to bounce these ideas off of."

It's a concept we could desperately use in our politics.

And it's a concept, interestingly, that is also a foundational story in U.S. culture — but often gets overlooked.

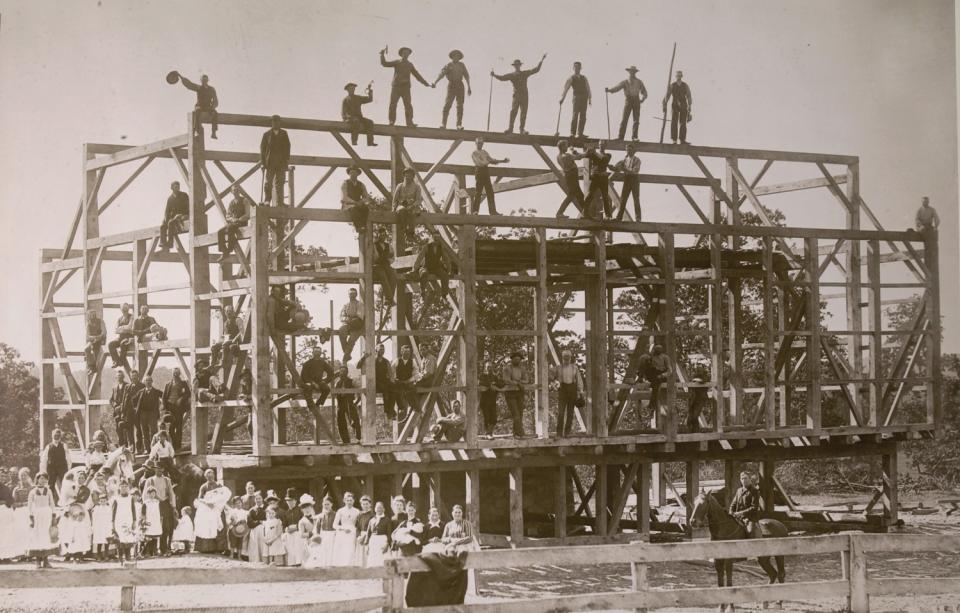

In the 18th and 19th centuries, rural communities often got together for the communal events known as barn raisings. People would gather to pool their labor and build in a day what might have taken an individual weeks or months to construct. (It's a practice that continues among some religious communities such as the Amish.)

Images of barn raisings as ideals of the collective have appeared in many New Deal-era murals, including post office murals in New Jersey and upstate New York. Vintage photographs from the 19th century are also plentiful.

One of my favorites is held by the Massillon Museum in Massillon, Ohio. It is from 1888 and is attributed to photographer Theodore C. Teeple. It shows men and women gathering around a barn-in-progress on a property held by one Jacob Rohr.

According to Margy Vogt, who wrote an essay on the image for the museum's 75th anniversary catalog, this barn raising gathered more than 200 community members — and it was a party. While the men built the structure, the women produced a gargantuan feast of beef roasts, hams, fresh bread and more than 100 pies. The image, she writes, "illustrates the spirit of sharing, helping, working together, or volunteering."

We'll need to channel its spirit — its American spirit. Because we're not getting through this pandemic as individuals. Like it or not, we're in this together.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.