Cygnus Spacecraft Leaves the Space Station After Giving It an Orbital Boost

A Cygnus cargo spacecraft left the International Space Station (ISS) today (July 15), nearly two months after it arrived with supplies and science gear for the station's six-person crew.

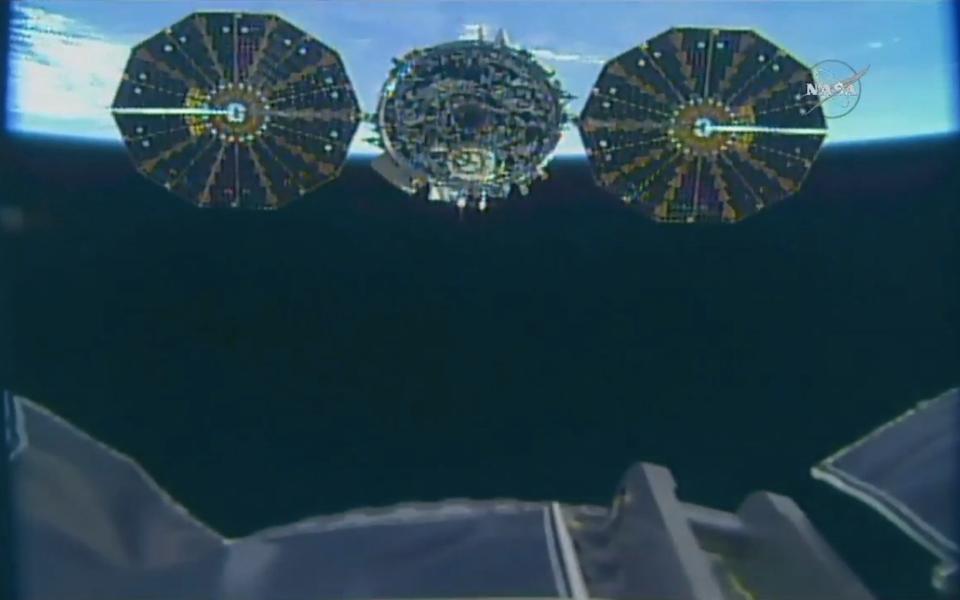

The uncrewed Cygnus OA-9 spacecraft, also known as the "S.S. J.R. Thompson," departed the ISS at 8:37 a.m. EDT (1237 GMT), when European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst and NASA astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor set it free using Canadarm2, a 58-foot (18 meters) robotic arm that the astronauts controlled from inside the ISS.

It will remain in low Earth orbit for the next two weeks to deploy six small satellites called cubesats using the external NanoRacks CubeSat Deployer. After that, it will deorbit and fall toward Earth, burning up in the atmosphere somewhere above the Pacific Ocean. [Launch Photos: Orbital ATK's Antares Rocket & Cygnus OA-9 Soar to ISS!]

.@Astro_Alex and @AstroSerena released the @NorthropGrumman #Cygnus cargo craft from the @CSA_ASC Canadarm2 at 8:37am ET today ending a 52-day stay at the station. #AskNASA https://t.co/1mgSEdHCD1 pic.twitter.com/RQ16Bu6DzG

— Intl. Space Station (@Space_Station) July 15, 2018

Built and launched by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (NGIS) — a private aerospace manufacturing company formerly known as Orbital ATK — the Cygnus OA-9 spacecraft lifted off May 21 on an Antares rocket from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Wallops Island, Virginia.

It arrived at the ISS on May 24 with 7,385 lbs. (3,350 kilograms) of science experiments, food, clothing and hardware and other supplies for the six-person crew of Expedition 55. But the mission's payload wasn't all it gave to the space station — before beginning its journey back to Earth, the Cygnus provided one last parting gift: an orbital boost that raised the station's altitude.

While the Cygnus was still docked at the space station's Unity module on Tuesday (July 10), the spacecraft fired its main engine for 50 seconds as part of a test to determine whether the cargo ship can be used to raise the space station's orbit, Frank DeMauro, Vice President of Advanced Programs at NGIS, told Space.com.

About the size of a short bus, the Cygnus may look puny compared to the ISS, which is as big as a football field. But its powerful Delta-V engine provided enough thrust to raise the space station by about 282 feet (86 meters). "The burn went extremely well," DeMauro said. "The spacecraft behaved exactly as we expected."

"We have several thrusters on the spacecraft that we use for controlling the spacecraft, but we have one big engine that we use … to actually raise our orbit from where the Antares rocket left us off up to the station's orbit," DeMauro said. "So, we looked at that and said, that engine has enough thrust and is very efficient, and we could use that engine while we were attached to the space station as a way to provide a boost to the station orbit."

The ISS already has a way to boost its own orbit using on-board thrusters, but "right now all the orbit raising is done by the Russian side of the space station," DeMauro said. Aside from the Russian thrusters, Russia's Progress cargo spaceships can also boost the space station's orbit. When the Cygnus boosted the station's orbit on July 10, it became U.S. spacecraft to raise the orbit of the ISS since the space shuttles retired in 2011.

"It would be of NASA's interest for them to have the capability by Cygnus so that we could be either a backup capability or a complementary capability to what the Russians already do," DeMauro said.

On average, the ISS orbits Earth at an altitude of about 248 miles (400 kilometers). A tiny amount of atmospheric drag causes it to slow down, lowering its altitude by about 1.2 miles (2 km) per month. [International Space Station: By the Numbers]

Being able to boost the space station's altitude not only keeps it from falling out of space, but the same technology can be used to help the ISS steer clear of orbital debris, to put the ISS in a good position to rendezvous with arriving vehicles, and even to eventually deorbit the ISS. But doing those things would require new modifications to the Cygnus spacecraft, DeMaruo said. Currently the cargo ship is only built to boost the space station's orbit, and the OA-9 is the first Cygnus to have given it a shot (and succeeded).

The S.S. J.R Thompson is the ninth of 11 cargo resupply missions NGIS (formerly Orbital ATK) has launched for NASA under a $2.9 billion contract. Another Cygnus, OA-10, is scheduled to launch to the ISS in November.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.