Decades after resettlement, tiny communities still dot Newfoundland's 'forgotten coast'

For many years before Confederation in 1949 and up until recently, the southwest coast of Newfoundland was often called "the Forgotten Coast" by the people who lived there.

The name stemmed from the sense that politicians, once they were elected, stayed away from the area. Pleas to provincial and federal levels of government, even for necessary services, went unheeded.

I became very familiar with that part of the province over some 18 years, from 1962 to 1980, when I travelled the southwest coast as a sales rep for a national meat-packing company. I also photographed and wrote articles about the area and its people for the Evening Telegram.

For nearly 100 years the cry of "the steamer is coming in," announcing the arrival of the coastal boat, would be heard weekly in the isolated outports of the province. These vessels — carrying the mail, passengers and freight — provided the lifeline that connected the dozens of communities along our shores.

The sounding of the ship's whistle announcing its arrival would see dozens of the residents rushing down to the wharf to welcome a stately vessel and its passengers as it docked.

In 1897 the building of the Newfoundland Railway from St. John's to Port aux Basques was nearing completion. The government had spent millions building it and now was faced with the formidable expense of its operation. It appeared the government of the day would be facing a large annual deficit, which might lead the country into bankruptcy.

The government, under Sir James Winter, entered into a contract with R.G. Reid, the builder of most of the railway, selling it to Reid for $1 million with the stipulation that he operate the system for 50 years. In return the government gave Reid large tracts of what proved to be valuable land, a large proportion of the entire territory of the island.

The contract included provisions for Reid to take over the telegraph lines and arrangements for his firm to provide mail service to cover the entire island.

According to Grand Bank historian Aaron Buffett, in his writings from the 1930s and '40s, "succeeding governments annulled the contract and our country had to pay heavily to appease the Reids."

As part of the Reids' contract, eight steamships were built to provide the mail service. Six of the smaller vessels were for the different bays, including the Glencoe for the south coast and the first Bruce for the Cabot Strait.

During 1899-1900 these boats inaugurated the services, which continued for decades with only slight changes and developments. The service between Argentia and Port aux Basques was weekly at first. In later decades it decreased into a fortnightly service as traffic increased and ports were added.

Until the early 1990s the only transportation link along the entire coast was provided by the Canadian National vessels. Although complaints against these boats were quite valid as far as scheduling and mishandling of freight were concerned, they were nevertheless the very lifeline of the 20,000 people who at the time lived along those rocky shores.

All communities, from the very smallest of just a few dozen families to the largest with a population of 2,000, had basically the same needs. Better schools and well-qualified teachers were hard to come by, communication systems needed to be improved, road construction was long overdue, medical services were lacking, community sewer systems were almost non-existent and jobs on the local fishing boats just weren't there.

To bring these essential services to even the larger communities would have cost millions. Governments turned a deaf ear toward the south coast and a hardly noticeable sprinkling of government money came to this section of the province.

People in some of the smaller outports became restless for a better standard of living and couldn't accept government neglect any longer. Families began to move away on their own without government financial help.

In the 1950s, the federal and provincial governments combined on what was to many people the infamous "centralization program," to move Newfoundlanders from small outports into larger centres.

Government grants were given to families to relocate, and south coast communities with names like Rencontre West, Pushthrough, Cape La Hune, Point Enragee, Richard's Harbour, Stone Valley, Pass Island and Grole began to disappear.

Many of the people from these settlements moved to the larger towns along the coast, such as Harbour Breton, Burgeo, Ramea and Gaultois, where jobs awaited on deepsea draggers or in fish plants. Some families moved to the Burin Peninsula, to St. John's and even to the mainland, where employment was assured and the bonds of isolation would be broken.

For years town officials, business owners and others complained about the inadequate service provided by CN, to no avail. During the 1970s I travelled the coast on the MV Hopedale, a vessel capable of sleeping 30 passengers.

In reality, there were times when it was reported it would pick up as many as 150 people at Port aux Basques, many of them forced to sleep on floors and in hallways en route to their homes in Burgeo, Ramea and other settlements down the coast.

Hundreds of people who had moved into the supposed growth centres saw their livelihood disappear as the fish plants closed and the fishing draggers were tied up.

In 1972, a network of local roads from the Connaigre Peninsula and Bay d'Espoir was connected with the Trans-Canada Highway. This finally gave more than a dozen communities from the eastern part of the southwest coast a means of travelling to the outside world by car or truck instead of having to rely on the coastal ferry system.

The collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery, resulting in the declaration of the cod moratorium in 1992, threw some 35,000 Newfoundland fishermen and fish plant workers out of work, devastating the outport economy.

This meant that hundreds of people who had moved into the supposed growth centres saw their livelihood disappear as the fish plants closed and the fishing draggers were tied up.

From 35 communities to 20

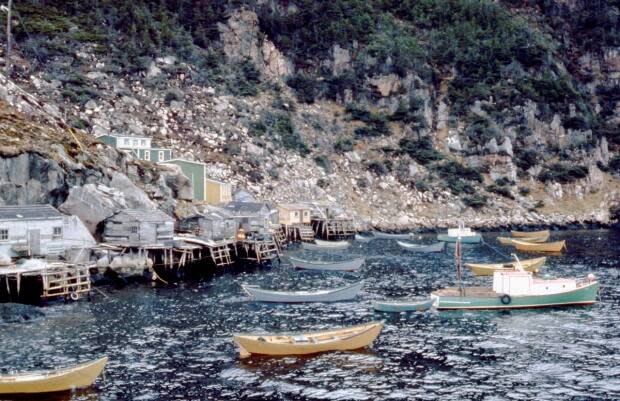

There were 35 communities scattered along the southwest coast when I first travelled it in the early 1960s. Today only 20 of these settlements remain, including six — Ramea, Grey River, Francois, McCallum, Gaultois and Rencontre East — that are still isolated and have only a ferry connection with the outside world.

The Glencoe, built in Scotland for $175,000, operated for six decades, mostly along the south coast, right up to 1959. She was the longest-serving ship of the so-called "alphabet fleet" of vessels owned by the Reids.

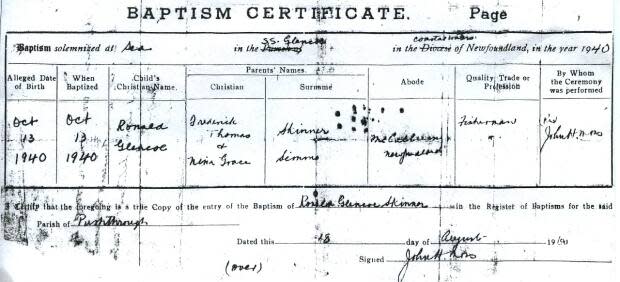

In October 1940, Nina Skinner accompanied by her husband, Fred, boarded the Glencoe in McCallum to go to Harbour Breton. She was expecting her first child within days and wanted to be at the nearest hospital to have her baby delivered.

The baby decided to arrive early, while the vessel was en route to Harbor Breton. With the help of the purser, who stepped up and helped with the delivery, Ronald G. Skinner first saw the light of day aboard the SS Glencoe.

His mom decided to name him Ronald — after the purser — and she chose Glencoe as the middle name for her new baby. Ronald Glencoe Skinner celebrated his 80th birthday on Oct. 13.

Skinner pursued the fishery all his life: first working on the offshore draggers in Nova Scotia and out of Gaultois and latterly inshore fishing, until he took an early retirement in 1999 due to the moratorium.

In 1973 McCallum had a population of 216, which over the years gradually decreased. Today, according to Skinner's wife, Amelia, only 30 people live there. There are just three school-age children in the community, one of them the teacher's child.

Amelia and Ron Skinner moved to Hermitage, where their son lives, in 2002, because she feels much more relaxed living within a 45-minute drive to the hospital in Harbour Breton.

Today, Ronald G. Skinner is still in good health and keeps busy, collecting kelp for his garden and occasionally going out fishing with his son, Dan.

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador