Domestic violence calls to police on rise during pandemic, yet some Alberta shelters have been quiet

When COVID-19 arrived in Alberta, it was no surprise to police the pandemic brought with it a jump in domestic violence calls.

Domestic violence rates typically go up when people are faced with a crisis, said RCMP Staff Sgt. Colette Zazulak, who oversees Alberta's community policing unit.

"It's like when you apply pressure to a rock and the fissures start to form. You would see increased violence and likely more severe violence as well."

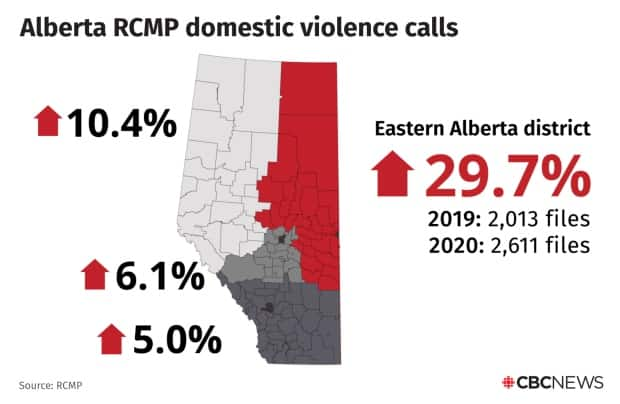

From mid-March to mid-September, RCMP in Alberta recorded a 12 per cent rise in calls involving domestic violence over the previous year.

Edmonton police saw a similar rise, with 13 per cent more calls in the first nine months this year over the previous three-year average.

While calls to police were on the increase, some women's shelters, where victims often go to seek refuge, were seeing a decrease in use of their services.

"We really saw a drop in calls, not only in Alberta but really around the world," said Jan Reimer, executive director of the Alberta Council of Women's Shelters.

Restrictions set in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 isolate vulnerable people, limiting opportunities to safely leave an abusive situation, Reimer said.

Fear of contracting the coronavirus in a communal setting like a shelter may also have prevented them from leaving, she said.

"It makes people scared to go out and seek help, scared for their children and what they may be exposed to."

'It's quite scary'

RCMP officers in Alberta's eastern district have responded to about 600 more domestic violence calls so far during the pandemic, compared to the same period last year.

That area of Alberta has consistently had a higher rate of domestic violence compared to the rest of the province. The RCMP doesn't know why the increase is so marked there.

"Sometimes, that can be for a variety of reasons. Things like isolation, if people are in rural and remote communities. We know they're not close to the hub where there are more services, even with the pandemic," said Zazulak.

Yet the only shelter in St. Paul, about 200 kilometres northeast of Edmonton, has been quiet until the last few months, said Noreen Cotton, executive director of the Capella Centre Women's Shelter.

"That's what's really disturbing, because we know people need help and they're not reaching out."

The women who did seek help experienced more severe violence than usual, Cotton said.

"They're just waiting until it's absolutely the worst case scenario before they'll come into the shelter," she said. "It's quite scary."

At the same time, the centre's outreach worker, who helps survivors of domestic violence who don't want to stay in the shelter navigate the justice system, has been busier than ever.

Referrals from the RCMP to the outreach program have increased by half between March and August, Cotton said.

"It's really shown its value because of the decrease of women trying to come into shelter," Cotton said. "It addresses that gap that became very evident during COVID."

In August, the Northern Haven shelter in Slave Lake sat empty for the first time since Shelly May Ferguson became executive director in 2012.

"It's eerily quiet," Ferguson said. "We know domestic violence hasn't been solved."

Fort McMurray's Waypoints emergency shelter currently houses 10 people, instead of its usual 40, according to its operators.

Different housing model

Not all shelters are experiencing the same disconcerting quiet.

Lynne Rosychuk opened the doors in May to Jessie's House in Sturgeon County, just north of Edmonton.

The shelter has been full since, albeit operating at a reduced capacity as a result of COVID-19 restrictions.

"We get calls every single day," Rosychuk said. "We've had women from other provinces that have stayed at our shelter. It's sad, really."

The shelter, built in honour of Rosychuk's daughter Jessica Martel, who was murdered by her abusive partner in 2009, was designed to accommodate big families and has a separate suite that can house COVID-19-positive guests.

"When you're already leaving a horrible situation, to be split up from your children would be the last thing you would want to have happen. So when we built this house, we took a lot of that into consideration," Rosychuk said.

Reimer said the pandemic has highlighted the importance of moving away from a communal shelter model to more private accommodations.

"A communal environment is not the best way to provide support services for women," she said. "The pandemic is really bringing that to the fore, but we knew it previously."

Bystanders play crucial role

As the pandemic continues to play out, friends and family members must play a larger role, even intervening if they suspect domestic violence, Zazulak said.

"Oftentimes the police are the last to know that violence has been occurring," she said.

"Everyone plays a role in this, in both sharing information, supporting victims and speaking up when they see abusive behaviour, even if it's not criminal."

Threats of violence should never be ignored as they can be the precursor to deadly action, said Reimer.

"Often people take these threats as some kind of a joke; they're not," she said. "Take it seriously."

Reimer said she expects the demand for shelter spaces will grow as the pandemic continues.

"There'll be greater demand for services as we go, not just the next couple of months, but over the next several years."

Help and advice is available through Alberta's family violence info line by calling 310-1818.

Support is also available by calling the Alberta Council of Women's Shelters' confidential and toll-free line at 1-866-331-3933.