Dr. Christopher Patey is his name, removing fish hooks is his game

Every summer, thousands of people look forward to heading out onto the water and reeling in cod during the recreational groundfish fishery.

Dr. Christopher Patey, an emergency room doctor in Carbonear, looks forward to it too, but for a different reason: he's noticed a correlation between the recreational fishery and fish-hook accidents.

"As soon as this food fishery came around — clinically anyway — in the front line we're saying, 'Wow, like, they just keep coming in.' What we found was an interesting mix of patients. There's kids that show up, there's 90-year-olds that show up and then there's everyone in between that as well."

Patey could find only one study on fish-hook accidents, and that focused on fisheries in Alaska.

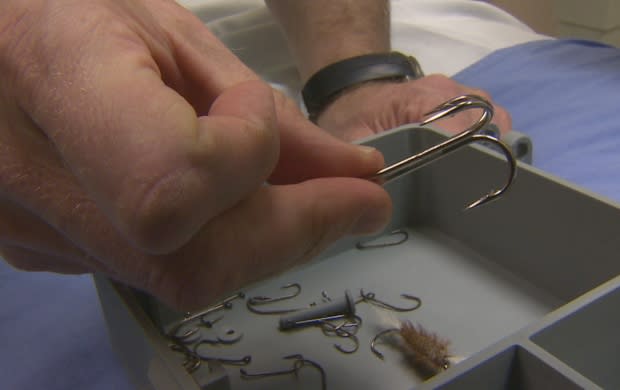

Most fish-hook injuries occur in the fingers

He decided to conduct his own review on fish-hook injuries, looking at 165 Eastern Health medical files from 2013 to 2015.

Patey found that 55 per cent of all reported fishhook injuries occurred when the food fishery was open.

About 76 per cent of patients were male, and 81 per cent of the injuries occurred to a finger, thumb or hand.

The average patient's age was 51.

Patey said the food fishery is so important to Newfoundland and Labrador culture that everyone heads out in a boat instead of just commercial fishermen who are used to handling the gear.

"You're actually having families going out, and with the number of feathered hooks flying around then you're getting these hooks getting caught."

The goals of Patey's study, entitled Fishhook Injury in Eastern Newfoundland: Retrospective Review, were twofold.

One, he wanted to find out how other doctors and nurses removed fish hooks, and two, whether the recreational fishery led to an increase in accidents.

Techniques on removing fish hooks

About 56 per cent of documented fish-hook removals were by the advance-and-cut technique, where the tip of the hook is pushed up through the skin so the barb can be cut with wire cutters, allowing the hook to be pulled out the way it went in.

Patey said while this is the preferred method of health professionals, it's not the best one.

Patey has been training staff and interns on the string-yank technique, which he learned from a doctor in northern Ontario.

"You grab a length of line, a 12- to 18-inch loop [of] pretty strong stuff, because you are going to put a bit of force on this," he said. The loop is placed on the curve of the hook, he added, and then, "You put your finger on the eye of the hook and on the count of three you pull.

The hook flies out of the skin and can be used again, he said.

Easy to learn and perform

Patey said people trained on the technique rank it highly for being easy to learn, perform and for causing less tissue damage.

"Just recently I had a gentleman who was trying to pull in a large sea trout, a German brown," he said.

"As he was pulling it in the beach, as he leaning back on his rod the fly came out of the fish's mouth and then hooked him in the cheek. I said to him, 'I can freeze this and we can push it and cut it or I can just flick it out.'"

The man said he didn't like needles, so Patey used the string-yank technique successfully, with the fly flicking across the room.

Patey says the man said he'd probably use the fly again.

"It's kind of fun for everyone in the department to have something unique that happens and we kind of make it an event when we remove these fish hooks."

Patey says there's usually three feathered hooks on a line, and that adds to the chances of people getting injured.

"I'd encourage people to really watch it. If you have kids on the boat, maybe one hook is plenty."

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador