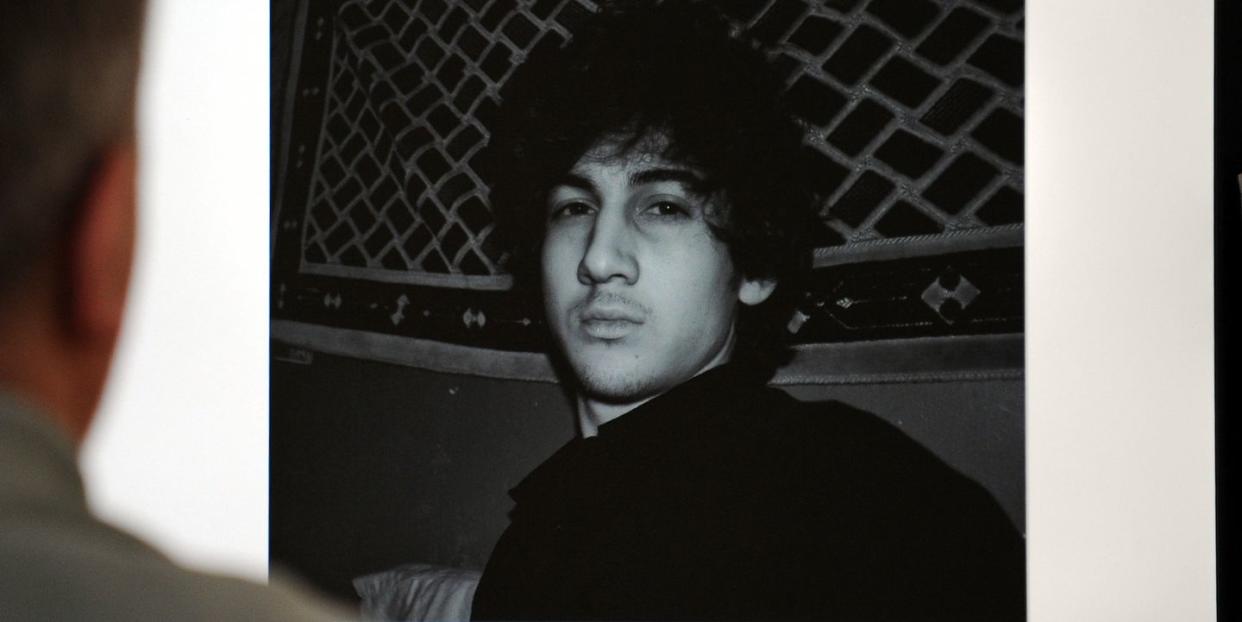

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Will Be Nervous About the Outcome of the 2024 Election

On Monday, they ran the Boston Marathon for the 125th time. The men’s race was won by Benson Kipruto, and Diana Chemtai Kipyogei was the women’s champion. Both were from Kenya. The pandemic pushed the event into the fall rather than its traditional start date on Patriots' Day, which is a Massachusetts holiday because the state legislature decided citizens of the Commonwealth (God Save It!) needed a holiday in April.

(We also have Evacuation Day, which, every March 17, celebrates the day George Washington scared the British out of Boston. This came about in 1901 as a sneaky way to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day without any of that pesky church-and-state stuff.)

Two days later, in a weird kind of symmetry, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the survivor among the two brothers who bombed the race’s finish line in 2013, had his day before the United States Supreme Court. Tsarnaev’s lawyers were not arguing to reverse his conviction. They were trying to get the Court to uphold a federal appeals court ruling that had thrown out Tsarnaev’s death sentence on the grounds that a) the trial judge failed to ask prospective jurors about their media consumption, and b) he failed to allow the defense to use evidence that Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the older of the two brothers, had been involved in a triple murder prior to the Marathon bombing. Tamerlan Tsarnaev was killed during a wild late-night shootout with police in Watertown in the immediate aftermath of the crime. The defense wanted the evidence of the prior alleged murders entered in order to argue that Dzhokhar was under his older brother’s sway when participating in the bombing.

According to Amy Howe of SCOTUSBlog, a majority of the justices were not impressed by either of these causes of action, or the use to which the appeals court had put them.

Wednesday’s oral argument focused primarily on the second issue in the case – whether the judge was wrong to exclude evidence of the 2011 triple murder. Representing Tsarnaev, lawyer Ginger Anders told the justices that Tsarnaev’s defense at his sentencing rested on the theory that his older brother had “indoctrinated” him and was more likely to have been the leader in the bombings, making Dzhokhar Tsarnaev less responsible and therefore less deserving of the death penalty. The 2011 murders, Anders explained, demonstrated Tamerlan’s commitment to “violent jihad,” but the exclusion of that evidence “distorted the entire penalty proceeding.” By contrast, Anders continued, allowing Tsarnaev to tell the jury about the 2011 murders “would have changed the terms of the debate.”

Four members of the Court’s conservative bloc, including Chief Justice John Roberts, peppered Tsarnaev’s lawyer with questions on this point.

Chief Justice John Roberts suggested that introducing the evidence would have turned attention to something that could not be resolved – who committed the 2011 murders in the first place. And it wasn’t a question of whether the jury should believe that Tamerlan or a friend of his, Ibragim Todashev, was ultimately responsible for the 2011 murders, Roberts observed, because both of them are dead and could not testify.

(And thereby hangs a tale. Todashev is, as Roberts pointed out, dead, because he was shot and killed by an FBI agent in Florida a week after the bombing as he was about to sign a statement admitting his role as Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s accomplice in the triple murder. The details of that episode are still shrouded in mystery. Masha Gessen’s book about the Tsarnaevs, Two Brothers, is very good on the subject.)

Late in the oral arguments session, an interesting point was raised by Justice Amy Coney Barrett. What, she wondered, was the government’s “endgame” in all this? Even if the Court ruled for the government, the Biden administration has in place a moratorium on carrying out federal death sentences.

On the one hand, Barrett observed, earlier this year Attorney General Merrick Garland imposed a moratorium on federal executions, but on the other hand, the federal government is asking the justices to reinstate the death penalty for Tsarnaev. The jury, Feigin emphasized, imposed a “sound verdict,” and the court of appeals was wrong to reverse it. The Supreme Court should allow the jury’s verdict to be carried out. At a minimum, Feigin noted, the “easiest way to resolve” the case is to conclude that the jury would have reached the same verdict even if the judge had asked jurors about pretrial publicity and had allowed Tsarnaev to introduce his additional evidence.

As I said, most accounts of the day found the Court leaning toward reversing the appeals court and upholding Tsarnaev’s death sentence, Barrett’s conundrum notwithstanding. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is now just another guy nervous about the 2024 election.

You Might Also Like