It's easy — but wrong — to blame gender bias for Canada's sudden lack of female premiers: Robyn Urback

Soon, there will be no female premiers in Canada. Back in 2013, there were six. The lazy way to explain this is that voters have failed to suppress their philistine prejudices.

It is indeed one of the most facile, overused arguments in politics: that a woman's gender plays a more-than-nominal role in her electoral defeat. By this line of reasoning, the politician's skirt at once obscures her accomplishments and elevates her failures. Impossible to prove but nevertheless often peddled, the claim is not that she is booted because she is a woman, but that she is booted because she is judged more harshly, by virtue of being a woman.

In theory, this makes sense, and is probably a factor — to a very nominal extent. Of course our perceptions of others are coloured by what people look like, or where they come from, or what they wear. Liars will insist that the fact the prime minister still looks like he was plucked from the set of Saved by the Bell has no bearing whatsoever on how Canadians assess his leadership, but as I say: liars. Of course we judge people based on superficial factors, and those judgments affect how we interpret their actions.

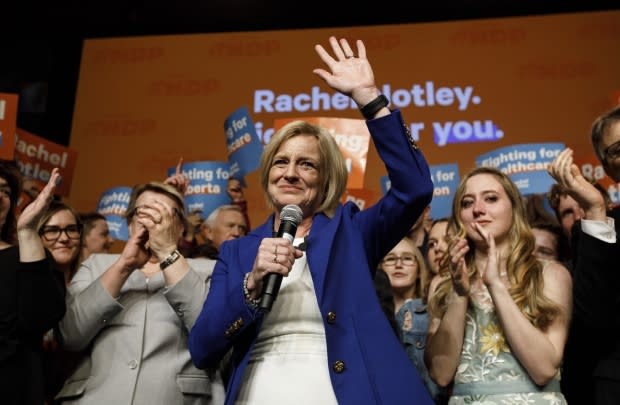

But the significance of these perceptions tends to be grossly overstated in post-election analysis, especially when trying to explain trends. To wit: it's easy to suggest, looking at the Moore's commercial that is Canada's slate of first ministers (marked by the upcoming exit of Canada's last remaining female premier, Rachel Notley), that Canada is in the midst of a sort of sexist regression, with voters declining to elect women to second terms. From afar, it sure looks like some sort of prejudice is at play — as explored here, here, here and here.

But that interpretation doesn't hold up when we look at the conditions that led to each individual ouster. Notley actually enjoyed relatively high personal favourability numbers in comparison to UCP Leader Jason Kenney, but by the time the Alberta election came around this year, the province was simply done with the NDP; the price of oil had tanked, workers had been laid off in droves, the Energy East pipeline was dead and the carbon tax was in full swing. Never mind a male candidate, Jesus himself could have run as the NDP leader, and it still would have been a tight race.

Same goes for Ontario. As the clock counted down on the Liberals' 15-year tenure, pundits began wondering whether Kathleen Wynne's gender and sexuality — which remained unchanged from the time she was elected Liberal leader and re-elected as premier — might explain why she was suffering from such low approval numbers.

It was perhaps a legitimate question to pose to those who hadn't heard about the OPP investigations, cronyism allegations, ballooning debt, exorbitant waste and other scandals that had rendered the prospect of another Liberal term in government utterly unpalatable to so many Ontarians. And perhaps a man in a suit, instead of a woman in a dress, could have softened those scandals in the eyes of the electorate, but alas, the last man who tried was so unpopular he resigned.

Thus, the "women are judged more harshly" trope doesn't really explain what happened on an individual level in Alberta, or Ontario, or the other provinces that have lost their female leaders over the past few years. It's a lazy explanation for a complex set of circumstances — one that undermines voters' legitimate grievances and reduces them to symptoms of unconscious bias.

Canada is likely not experiencing a sexist regression so much as it is a desire for change at the provincial level, yet the change options presented to voters all seem to use the same bathroom. That is partly a function of largely internal party elections, where it is not as simple as the one with the most votes wins; it's also about finicky intraparty politics, including who can win the most endorsements from the existing caucus, earn the backing of exiting candidates, who can hire the best strategists and who can collect the most fundraising dollars.

The United Conservative Party in Alberta was going to be run by a man — it was just a matter of whom. The Progressive Conservatives elected Doug Ford (even though Christine Elliott actually earned more votes) making him Ontario's choice for change.

The Quebec election was a race between the incumbent man and the new one. The upcoming Newfoundland and Labrador election will be the same thing. And the looming federal election will be a choice between the incumbent male prime minister and the two recently elected male party leaders, whose respective party leadership races essentially came down to a rough-and-tumble battle of mostly dudes.

Christine Elliott could have just as easily walloped Wynne's Liberals — in fact, she might have done better than Ford based on March 2018 polling that suggested she'd widen the PC tent. And I suspect that, had the national Conservative leadership race turned out differently, Lisa Raitt as leader — facing off against a wounded Justin Trudeau — could have similarly broadened the party's base.

But Canadians can't vote for women unless parties elect them to lead, and parties declining to do so is a big reason why Canada's slate of first ministers looks like a men's lawn bowling lineup. Canadians have been voting for change at the provincial level. It just so happens that all of that change seems to look the same.

This column is part of CBC's Opinion section. For more information about this section, please read our FAQ.