How Edmonton's drug court program changed the lives of two former drug users

Two participants of Edmonton's Drug Treatment Court Service say the program not only saved them from self-sabotage, it rescued them from years in prison and allowed them to heal.

The program is set to expand in April and 28-year-old Alana Lambert and 33-year-old Roberto Diaz say they want to use their experience to help others suffering from addiction.

In October last year, the province announced it will provide $20 million dollars to expand the drug court treatment service in Alberta.

According to Grace Froese, program manager at the Edmonton John Howard Society, funding will be provided in April to help drug court services in Edmonton double its capacity

The Edmonton program currently serves 21 participants. As of last Friday, it had 27 people waiting to get in. With the added funding, the program is expected to serve 40 people.

The program only exists in Edmonton and Calgary, but it also will soon be set up in other major urban centres like Fort McMurray, Red Deer, Lethbridge and Medicine Hat.

"This is something I was hoping for ever since I started this position six years ago," said Froese, who will help train staff for the expansion.

"This is something that's needed. Everyone should have access to this type of program."

'I knew I needed help'

Alana Lambert says she started using hard drugs when she was about 15. Soon, she became addicted to heroin.

"For me, I was lost in addiction. I lived a life full of chaos and criminal activity, [which] was based out of the fact that I needed a means to find more drugs."

In 2016, Lambert was arrested for theft and drug possession charges. She was missing court dates and breaching orders. Her lawyer told her if she didn't enrol in the drug court program, she'd spend a substantial amount of time in jail.

"At that point I was very sick and I knew that I needed help," she said.

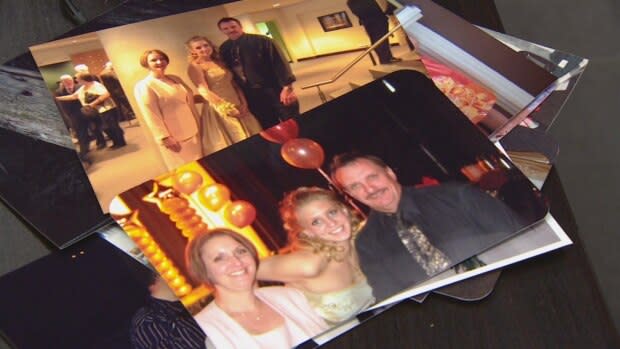

Lambert says a huge motivation to enrol in the program was her family, who no longer accepted her at family functions, cut her off and became scared of her.

"Rightly so, I would've been scared of myself," she said. "My dad doesn't cry very often and when I saw my dad cry, I knew that something had to change."

In 2017, Lambert enrolled in the drug court treatment service. She became sober in October of that year and graduated from the program in May 2019.

She said the most difficult part of the program was being accountable for herself, showing up on time to her appointments and changing her lifestyle.

"Coming in every morning we had to screen all the time so peeing in a cup in front of a couple of people is very nerve-racking in the beginning, but it's something you get used to," Lambert said.

"Now I live a day-to-day life and it's easy to get up and go to work and be accountable to my adult life."

Lambert now works at a dealership in Edmonton as a fleet assistant. Come April, she and Roberto Diaz will start working part-time at the John Howard Society as peer support workers.

"I do want to do something with people because I really feel that my experience can help other people," she said, adding she wants to pursue a career in social work.

Healing

For Roberto Diaz, drug court helped him heal from past wounds and pain. By the time he enrolled in the program in 2017, Diaz was already a few months sober, despite having suffered from addiction for a large part of his life.

Diaz says he began using and selling drugs when he was 19. He said he had a long list of run-ins with police and nearly 10 charges of drug trafficking. He also went to a couple of drug treatment centres, with little success.

"I wasn't trying to stop using [drugs], I was just trying to get the external voices to diminish or quiet down so I could go along with my business," he said.

Diaz recounts how he was once kicked out of treatment because he got into a fight and couldn't give up his phone.

"One of the delusions I had going into treatment was that ... I needed my phone, the number of people who needed me you know? I think it was one of the last things I had that I had any control over," he said.

In 2017, Diaz found out he was under investigation for manslaughter in a death resulting from an opioid overdose. He was looking at three and a half years in prison. At that time he was also homeless.

"I remember walking up 101 St. and 104 Ave. and walking toward the Hope Mission to get food, and I have two cloth bags and a backpack," Diaz said.

"I'm just wondering, 'where did it go so wrong? What happened?'"

In 2017, Diaz found himself at Recovery Acres, an addiction treatment centre in Edmonton. There, he was recommended drug court. In 2018, he started the program after being sober for five months and said it helped him heal.

"When you talk about communication through all these different programs it starts to resonate more," he said.

He now works full-time as a peer support worker with Alberta Health Services.

"My life is pretty amazing ... I really found my calling," Diaz said. "It's the people who I surround myself with that allow me to have the life that I have today."

Economic impact

The drug treatment court service started in Edmonton in 2005. Its purpose is to help participants break the cycle of crime and addiction, and make amends through restorative justice. It also aims to reduce costs for the courts.

"Those stories, if you did an economic impact assessment, would be way more valuable than just throwing somebody into jail," said Dale McFee, Edmonton's chief of police, referring to Diaz and Lambert's stories.

McFee heard their stories at a public police commission meeting last Thursday.

"It was an off-ramp that actually worked," McFee said about the drug court program.

"[It's] way less expensive, same process, same partnerships involved … [and] not trying to solve an issue in isolation. If we can do that, that's a huge win," McFee said.

The drug court operates on a basis of a guilty plea with a delayed sentencing process. Participants must take part voluntarily, be vetted by Crown prosecutors, and commit to the program for a year.