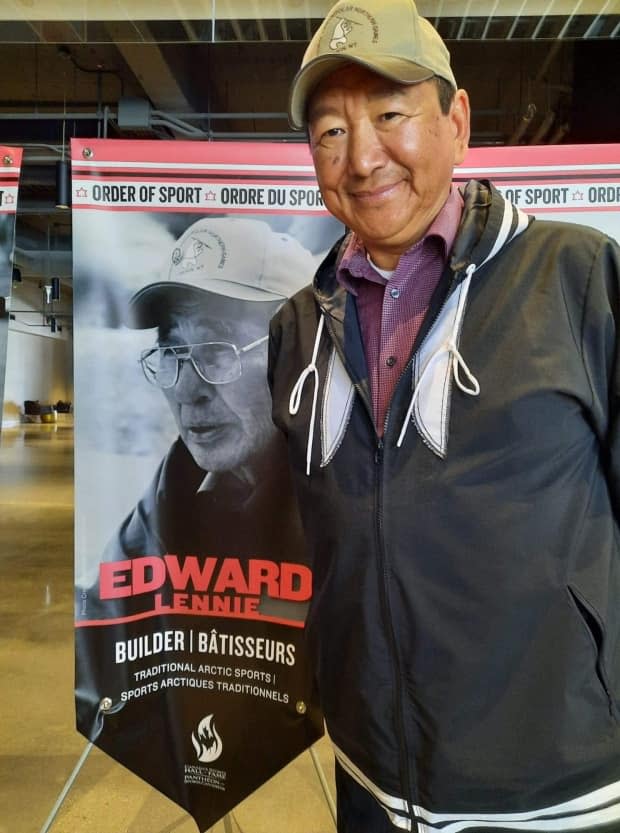

Edward Lennie, 'Father of the Northern Games,' to enter Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

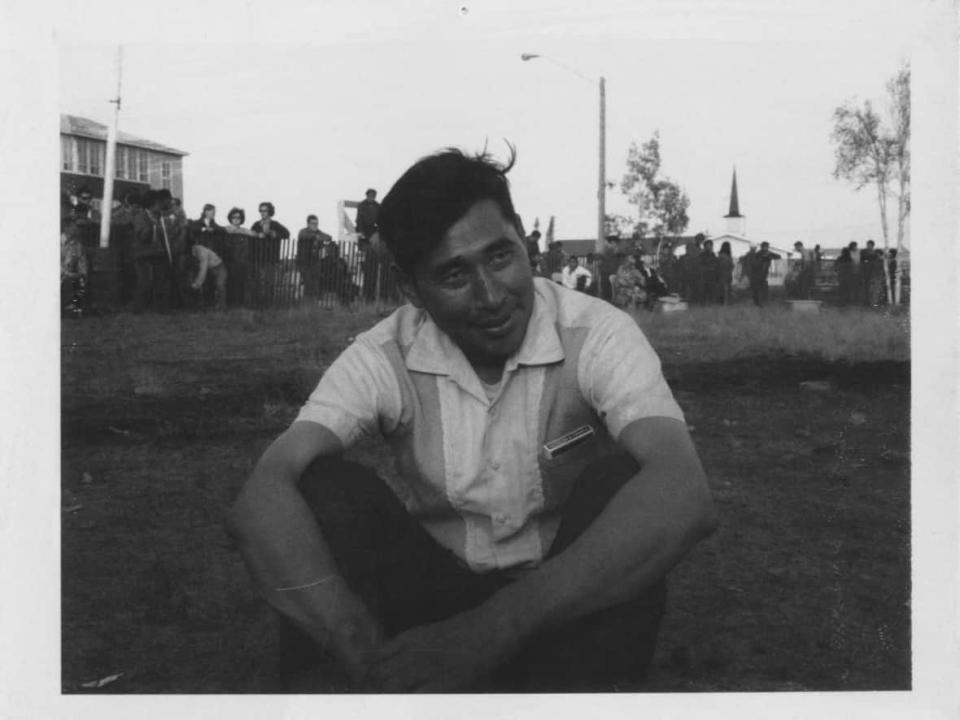

The late Edward Lennie was known as a leader, a mentor, and a passionate advocate of Arctic sports. Now he's being recognized for his contribution to sports at a national level.

Lennie, of Inuvik, N.W.T., died in 2020 at age 86. He will be inducted into the Canada's Sports Hall of Fame this fall.

His son, Hans Lennie, said to be recognized with the Order of Sport is an honour.

"My father's dream has finally come true," he said.

Arctic sports are being recognized internationally, but Edward Lennie — who became known as the "Father of the Northern Games" — hosted the earliest versions of the games at his house. It was a revitalization of the Inuvialuit games, and it became a gathering place for young people in the Beaufort Delta who wanted to learn.

"It all started from their kitchen room floor. Wow," Hans Lennie said.

It began with Mickey Gordon kicking the light bulb from the kitchen floor.

"It's all about strength, agility and endurance," he said.

If someone lost the games, it was time for pushups, said Lennie.

'Take it right to the Olympics'

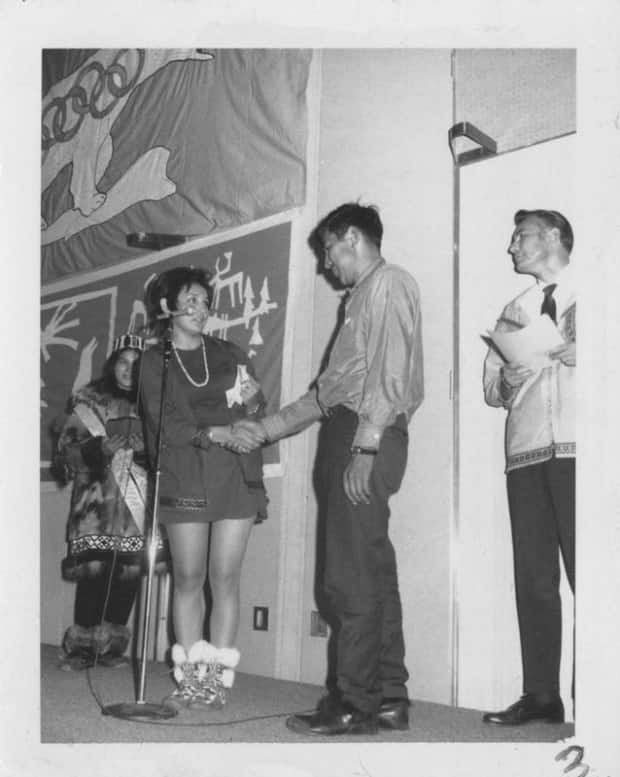

Edward Lennie successfully lobbied to include Arctic sports in the very first Arctic Winter Games held in Yellowknife in 1970. That year, he coached athletes who competed in the kneel jump, two-foot-high-kick and the arm pull, all traditional Arctic games.

Hans Lennie said his dad was passionate about the Arctic Winter Games, despite the inclusion of sports like hockey and volleyball.

"My dad thought … what's the Arctic about, you know? That's when he figured he needed to get involved and [former N.W.T. premier and childhood friend] Nellie Cournyea was a big help doing that," he said.

Hans Lennie said his dad worked with people like Roy Ipana, past chair of the Northern Games.

They had high aspirations to raise the profile of the events.

"He said in one of the meetings, we'll take it right to the Olympics. That happened in Vancouver [in 2010]. It was showcased as a demonstration sport," Hans said.

"Things like that really meant a lot," he said.

Hans Lennie said Ipana's wife Sandra was a major coordinator and the "main reason why the games continued."

Love of dancing

Hans Lennie said his dad was always very outgoing.

"Everyone knew too, up here in the Delta, the old time dance. He was one of the square dance callers. Dancing had a big part of it," he said.

Hans Lennie recalled how his dad once ran over to Reindeer Station just in his mukluks because there was a dance that evening.

"It was said when he showed up, it was, you know, it was going to be a lively dance."

Hans Lennie said his father's parents were Inuvialuit and Gwich'in.

"He got along with everyone, so it didn't matter where you put him," he said.

Hans Lennie said his dad, the "centre of attention," put the "love and passion to make the games complete."

Muktuk, geese and good memories

Traditional food was also part of it, and growing up they hunted a lot.

"Lots of that went to the Northern Games. They needed the muktuk. They needed the geese. You know, muskrat skinning, stuff like that. In a way, I would help."

Hans Lennie remembers at the start or even the middle of Northern Games, running out to bring in slabs of muktuk.

"You'd hear it on the mic … 'FRESH MUKTUK!'" he said.

Speaking about it brings up "good memories."

"You could just feel the love of people just seeing each other again," he said.

Hans Lennie said the games build character and self-esteem.

"It gives any athlete no matter the race, the colour … my father would help anyone that wanted to learn. That in itself says a lot."

"One of the biggest messages that my dad left to the athletes was not to allow them to say, 'I can't.' You always had to try."

His dad always encouraged people to try to be good at the little things.

"If someone beat you. You just walk over there and shake his hand," he said.